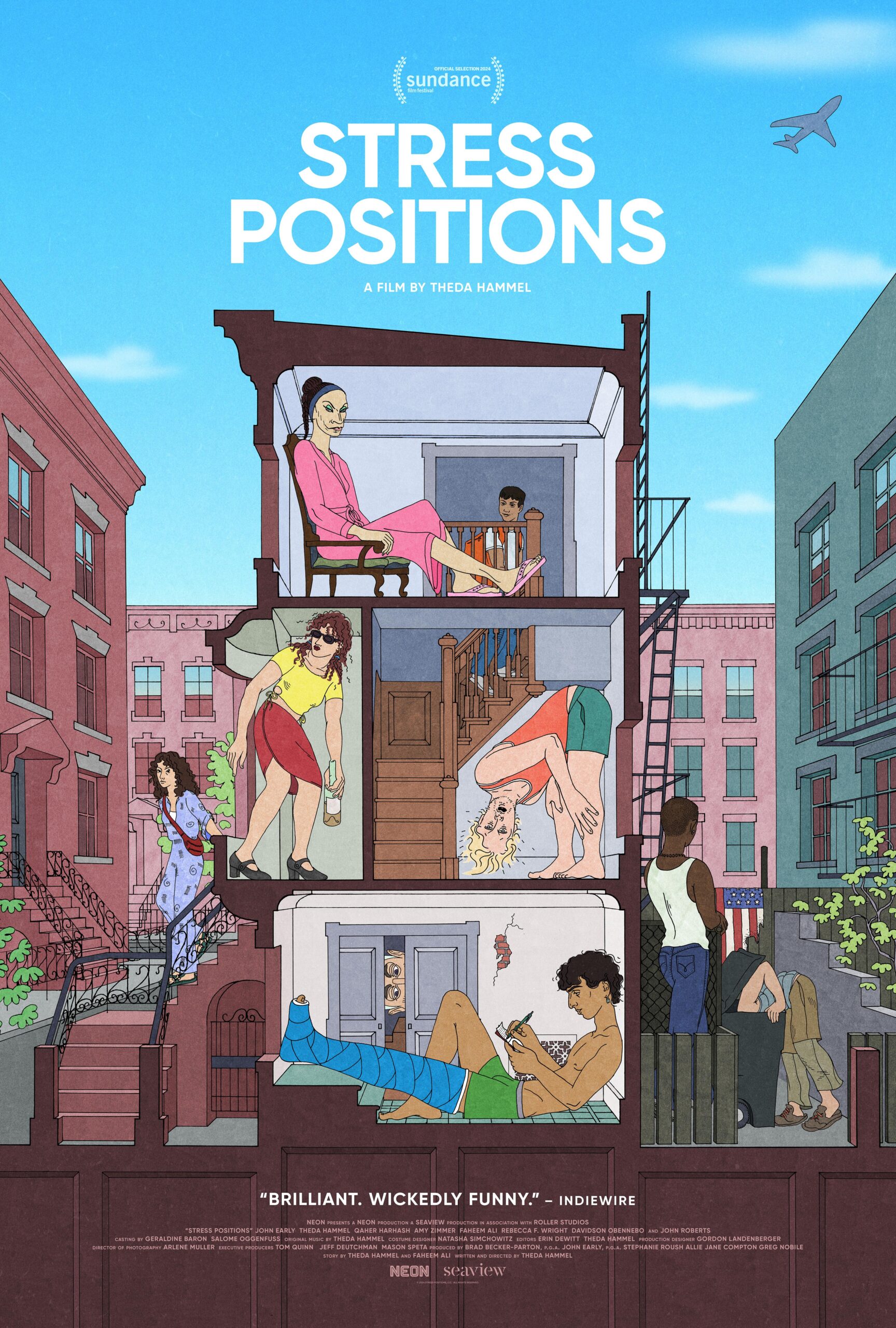

If you only have time to see one comedy this weekend, skip “The Fall Guy” and check out the indie comedy “Stress Positions” (2024). It opened last weekend, but it is still out with a few showings and deserves more. During an early pandemic summer, Terry Goon (brilliant physical comedian John Early) is quarantining in his husband’s rundown Brooklyn house and caring for his nineteen-year-old nephew, Moroccan model Bahlul (Qaher Harhash), his sister’s son, who lives in the basement with a projection screen functioning as a door. Terry is trying to beat back the hordes eager to meet his charge, which includes Karla (Theda Hammel, who also directed and cowrote) but fails.

“Stress Positions” is Hammel’s feature directorial and cowriting debut, and it is such a relief to watch a movie with a strong voice and unique perspective. It is not a perfect movie. It begins to lose steam and focus as it approaches the denouement, but there is thought and effort put into every detail. Hammel is a person who remembers, does not forget, the recent past and recreate it for our enjoyment. The camera follows Terry on a normal day zooming in on the details: as he sanitizes the takeout containers, a frenetic medium shot as he sprays disinfectant on cash before handing it to a Grubhub delivery man, Ronald (Faheem Ali, who also cowrote). The camera movement is very “Arrested Development.” Terry is a man who is desperate to make the right impression and act ethically but ends up being a hysterical mess despite his good intentions. He was the house husband suddenly shocked out of his comfortable existence because of his husband’s infidelity and impending divorce.

Karla, like Terry, is also a kept significant other and engages in some healing profession, perhaps physical therapy, which is a great excuse to touch other people. Unlike Terry, Karla is comfortable in her skin even as she navigates other people’s homes and bodies confidently and closely manipulating their limbs in her white, halter neck summer dress. There is a giantess grace to her stomps and sitting with her legs open, not in homage to Sharon Stone in “Basic Instinct” (1992), but because she is trans and does not feel the pressure to conform to all feminine norms. She has a girlfriend, is a bit of a moocher and is so physically and spiritually beautiful that it is easy to forget all her significant flaws.

There are two narrators: Karla, who recalls that summer, and Bahlul, who is recounting the time when his parents met until his time at his uncle’s place. Bahlul as narrator is way deeper than Harhash’s onscreen performance. Harhash plays Bahlul as if he is impressionable and a bit of a blank slate, but the narration signals that he is a deeply thoughtful person reflecting on his past. The unspoken elephant in the room is the spectre of his mother, Terry’s sister. He secretly fears her disapproval since he knows how she described Terry and the Western world. Bahlul’s mother may have contributed to making Terry into the person whom Bahlul meets. Well-meaning Americans surround Bahlul and confidently try to show off their knowledge while revealing their ignorance and bias, which never fazes Bahlul who is accustomed to his mother’s smug superiority and appropriation, but as a rationale for hate, not connection like his current hosts. At least this group accepts and encourages him.

The dissonance between Bahlul’s inner thoughts, vocal acting, and his on-screen performance could be because cowriter Ali should have played Bahlul since they are his words or maybe a more experienced actor. It would be intriguing to find out why Hammel and Ali decided to make that creative choice, especially since Hammel is probably playing the role that she wrote. Sure Ali would not fit the conventional standard of a model, but the character does not feel like a cohesive whole, and maybe he could have made it work. Ali’s role as a GrubHub delivery driver feels more substantial than most films’ main characters.

There are plenty of interesting supporting characters who do not seem like archetypes and would probably make riveting protagonists in their own movie. Oblivious to Karla’s indiscretions, Vanessa Ravel (Amy Zimmer), an author and Karla’s girlfriend, is struggling with writer’s block, fear and the past. She does not get enough to do, and if she was given more, perhaps the last act would not have faltered. It would have been interesting to show why she felt comfortable taking Karla’s life story and adapting it for her first novel. Coco (Rebecca F. Wright) lives upstairs from Terry, functions as his in-house IT, chooses to rarely speak, has an array of colorful outfits and a wide selection of wigs and ignores health protocols.

In the last of three acts, “Stress Positions” loses its narrative tightness as more characters get added on the Fourth of July 2020, and Hammel and Ali give viewers a glimpse of why Terry’s home was called a party house. Leo (John Roberts), the soon-to-be-ex-husband, arrives with party favors and party people, including his fiancé, Hamadou (Davidson Obennebo). The way that characters describe Leo contrasted with Roberts’ performance also feels disjointed. Leo is described as an affluent boy boss with scores of possible younger husband replacements, but it would be hard to imagine an executive Leo given Roberts’ performance in his off hours. There is no through line except hedonist dom, which feels lazy. How did such a bad boy snag the earnest Terry? Also I’m not a member of the community, but it felt as if gay men were at the forefront of health protocols, especially if they were from NYC during the AIDS crisis and had experience with skip tracing so Leo’s disregard of safety protocols feels like an exception, not a rule, which is aligned with his character. No group is a monolith, and maybe I’m playing respectability politics. Still credit where credit is due.

The final fifteen minutes is a whirlwind of almost wordless chaos leaving the audience to come up with their own conclusions thus departing from the established structure. “Stress Positions” leaves Bahlul’s relationship with Terry on an ambiguous note. Bahlul seems to take after his inscrutable mother in unexpected ways: disgusted with his roots and suddenly eager to escape everyone despite his earlier willingness to accept their defective hospitality. He escapes the cocoon to become like a butterfly. Earlier Karla jokes that men are in hell, and the only way to avoid hell is through women or becoming one. Instead of feeling like a triumph of self-expression and embracing identity, the ending feels bleak with a complete dissolution of the community togetherness witnessed earlier despite it being forbidden. Bahlul has become more resolute, but also flinty.

There is some subtle unspoken symmetry: an accidental swapping of tiny burgundy notebooks, the curse of the electric scooter, a furtive twenty-four-hour voyeuristic, nonconsensual peepshow, an obsession over glimpses of a person that the camera is unable to capture—echoes of Antonioni. It does not have to make sense to possess an oneiric, liminal logic never spelled out.

“Stress Positions” is the cinematic equivalent of literature. It feels as if it is an adaptation of a novel with narrators who understand others more than they understand themselves. In the end, Terry, who does not have a verbalized inner life, is left alone with his back pain and pulls the plug on our uninvited goggling. He asked to be taken off speaker phone, and he finally gets his wish.