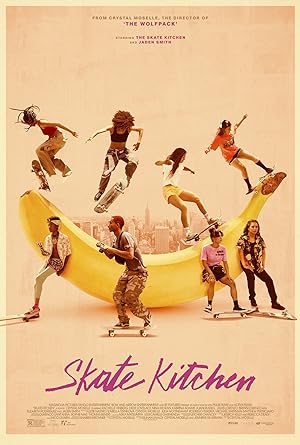

The Wolfpack’s Crystal Moselle finally released her second feature length film, her first fiction feature length film, Skate Kitchen. It focuses on Camille, a teenage skateboarder, as she tries to remain true to herself while figuring out how to navigate her relationships with her overprotective mother and new friends, which include other skateboarders, the majority of which are teenage girls.

Normally I enjoy financially supporting women directed films, and I love films set in New York City, but I purposely avoided this one in theaters. I was eager to see The Wolfpack, but dissatisfied by the actual product so I knew that I do not like Moselle’s amorphous narrative structure although she gives an ethical amount of autonomy to her subjects and correctly figured that she would repeat this approach in her second film. She is superb at sniffing out a story, not so great at conveying it.

Skate Kitchen is the title of the film and the group of skateboarders in this film and in real life. Even though the majority of these skateboarders are brown or black girls, the protagonist presents as a white girl even though she is probably of Puerto Rican descent. None of them fit the commercial image of the sexualized Californian skate boarder. I was plagued with nagging questions regarding why it had to be fiction, not a documentary, and why it could not focus on one of the actual members of the group. I know that the actual group did not feel marginalized, which is of primary importance, but I felt some kind of way about it. It was as if Moselle took their story then marginalized them from their own life; however knowing her style, maybe she asked them how the story should look. My feeling is similar to some viewers’ frustration that there can be future and better movies about experiencing life as a black person travelling in the Jim Crow South, but those movies probably can never be called Green Book. I wanted something different from what was offered so even though the problem stemmed from my perception, which no one else had and could not be valid, I could not comfortably cosign the movie’s mission statement though I wanted to: a group of diverse girls defying gender norms.

Finally I decided to watch Skate Kitchen at home instead of paying for a ticket because Jaden Smith is in it. I love the Smiths. I faithfully watch Red Table Talk. I wish them nothing but happiness and health. I adore his mother, who is my favorite Smith (my mom’s favorite is Will). That young man does not need my money, and it seemed like a cynical ploy to attract more money at the box office, but had the opposite effect and repelled me. The quality of the body of his work does not outweigh my need to keep money in my wallet. I’m the financial equivalent of a peasant to him so I’m going to keep my coins. It may not always be so.

Overall I think that Skate Kitchen met my initial impressions. I was transfixed by Kabrina Adams, but she is silent yet resplendent in her appearance. A more vocal and actual member is an openly lesbian character, played by Nina Moran, whose brash and bold style was refreshing, but while I applaud her open sexuality, similar to my response to Pariah, I’m less than thrilled that it looks so similar to adolescent male attitudes of objectification so if the path to acceptance for lesbians is by adhering to mainstream attitudes towards women and embracing conventional approaches to soliciting women, then I guess that I’ll always be disappointed when it does not look different. I have no idea what normal lesbian sexual attraction should or should not look like, but I know what I don’t like, and I don’t like it when guys do it, and apparently my reaction does not change when the gender changes even if I intellectually understand that one is more empowering than the other. Critics have compared this movie to Kids, and I hated Kids, particularly that whole pubescent sexual aesthetic.

I was fortunate enough to hear Moran speak on a TEDxTalk online after the movie and was completely impressed so I suspect that my instinct that a documentary would be better than imposing a constructed albeit meandering narrative to structure what we’re really interested in seeing, girls skateboarding, is correct. I have zero interest in skateboarding, but was transfixed by Moran’s talk whereas Skate Kitchen shows how the central character keeps recreating her conflict with her parents’ in different settings such as her relationship with her newfound friends. It then morphs into a completely ill advised and disastrous crush on Smith, which even he bats away like a volleyball. She creates an exile cycle. Then for the rest of the movie, I was needlessly worried that there would be a sexual assault, not from Smith’s character, but his friends, but I am relieved to say that the film never went there.

After I watched Skate Kitchen, I did watch the original short film online, That One Day, which is more engrossing than the feature length film even though it has oneric elements and is not a documentary, but a commercial. Critics laud the film’s depiction of friendship, and initially it is nice to see girls just casually kick it though it seems more focused on sex than the original short film. Were these critics watching the same film? Because the group turns on her like the ladies in waiting from Mary Queen of Scots after a new member violates a crucial rule. How many movies about male skateboarders ends with the friends breaking over a girl who isn’t interested in him? I don’t remember that happening in Catherine Hardwicke’s Lord of Dogtown. Even in a film reveling in girls defying gender expectations, it proliferates gender expectations about friendships between teenage girls.

The best change in the movie is casting Elizabeth Rodriguez as the central character’s mother although the actual character that she plays leaves much to be desired. Is the home experience of a female skateboarder similar to the experience of children who discover that they are LGTBQ and come out to their families? If the answer is yes, damn, I’m sorry, but if the answer is generally no, then this movie needed to dial it way back.

The most nuanced scene in Skate Kitchen is when she is rolling with a group of guys, and they run afoul on some private property. The constantly shifting power dynamics and different types of privilege and expectations were brilliant and uncomfortable in the best way: race, gender, socioeconomic, etc. There are explicit and unspoken rules being violated in that scene, but the main character’s exploitation of the unspoken rule is clever and insidious. It is the most deliciously ambiguous and threatening moment of the film.

I would not recommend the movie other than to appreciate the physical expertise of and early social dynamic of Skate Kitchen. It suffers from the problems endemic to many independent films. It falls into conventional pitfalls while trying to be different, but only succeeds in eschewing the things that make movies appealing.