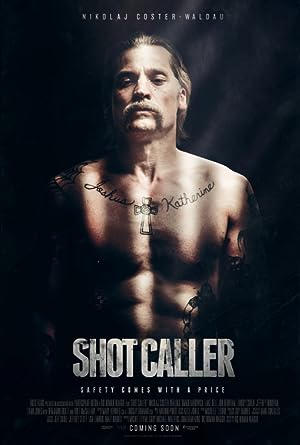

“Shot Caller” (2017) is supposed to be a character study of Jacob (Game of Thrones’ Nikolaj Coster-Waldau best known for playing twin lover Jamie Lannister), a successful businessman who ends up incarcerated when he takes responsibility for a tragic accident. Now he must learn how to survive behind bars and becomes known as Money. Once he has served his time, he learns that he is still trapped in a life of crime and is expected to still obey gang rules.

I made a mistake and watched the special features after I finished the movie. Nothing takes you out of a film faster than having a Dane and Benjamin Bratt telling you about the hard knocks of prison. Sirs, you are actors who did research, maybe visited and are just parroting lines in the movie. I don’t doubt their sincerity and earnestness, but nothing throws cold water on a project faster than artists talking about what life is really like for some people. “Shot Caller” may be more of a fantasy than any of their other work.

“Shot Caller” makes Jacob successful enough to survive prison life without looking like a punk, but stupid enough that he is oblivious to things like cameras, which to be fair is consistent and how he landed there in the first place. If it was a realistic film, it would be about a young man who started with issues in school then slowly the system processed him. Instead Money rises through the ranks rapidly until he is talking to head honchos and wheeling and dealing in the criminal underworld. The only thing that distinguishes Ric Roman Waugh’s vision of the actor’s blue collar fantasy of being a mover and shaker in the criminal underworld in movies such as “The Town” (2010) or the fantasy that a white collar man can leverage his success in the sphere of the lower classes as the protagonists did in “Arbitrage” (2012) and “The Lincoln Lawyer” (2011) is the story’s adherence to old tropes of masculinity requiring suffering vulnerability in silence, being alone and not permitted to enjoy normal life in order to continue protecting those that they can only love from afar. He throws a little nightmare into the fantasy, but he is not a trailblazer, just a retread.

Men inspect their wounds silently, usually in a bathroom mirror and weep alone for the sacrifice that they must make to protect women and children. While “Shot Caller” may not fit into the neo-Western genre, it does feel as if it sniffs around those edges except more melodramatic. Waugh’s film missed an opportunity though it has the seeds of a good idea: the idea of white supremacy being the backbone of corporate and prison life thus Jacob/Money’s success in both arenas! The protagonist’s name is not an accident either—someone who is always grasping at someone else’s heels to get ahead.

The titular character, the Shot Caller, starts as “The Beast,” who is loosely based on a white supremacist. Gangs in the prison are explicitly divided by skin color, but the corporate world adheres to similar rules. Before being sent up the river, Jacob jokes with his best friend that he is good at putting on his “knee pads” to make deals, using blow jobs as metaphors to climb the ladder of financial success. Men performing sexual acts in exchange for favor is the prevailing metaphor for the power hierarchy. Jacob is understandably scared of rape, but he is more terrified of sucking the wrong dick without getting something in return. I do not think that it is incidental that on screen, his first and last act in the gang is to insert an object into his anus.

Jacob only fails when he adheres to conventional morality—by taking responsibility for his first transgression. His unintentional crime hurts a longtime family friend, but without skipping a beat, Jacob’s wife (Lake Bell) shifts gears into protective mode and does not care about justice. Otherwise the rules of white supremacy and business are the same: obey the one in charge, group think, ignoring others’ humanity or relationships, a willingness to hurt people-offensive behavior framed as defensive, prioritizing “respect” over other values. Also women and people of darker hue cannot be insiders. They remain on the margins.

“Shot Caller” also obeys some white supremacist principles in its narrative structure. The black characters do not get names except for the parole officer. They act as archetypes-the new fish who gets raped, the first guy who assaults Jacob in prison. To be fair, Jacob is white, and we are following his story, but we get a glimpse into the Mexican gang life, and the head is given a back story, a name and some real dialogue. Movies treat characters humanely proportional to their skin color. This is not new.

Masculinity is the supreme unspoken rule. While there may be angst over being in exile from his better life and lip service to missing the company of women, “Shot Caller” prefers male communities despite its brutality, especially if one compares images of before and after. While playing basketball with his best friend, his hair is boyish, and he wears bright colors. It is dynamic and joyful. The film never shows Jacob at work, but during his leisure time. When he is in prison, it feels as if it is a recruitment ad for the army, a brotherhood, unity, except their uniform is white shorts and skins. When he reaches a higher security level prison, Jacob snaps to and joins them in their grueling exercise regime, which he embraces in his cell as he benches his roommate, Ripper, in his free time. He goes from an image of leisure to discipline. It feels like the male equivalent of a spa day—go to prison and get the body that you always wanted. After jail, Jacob gets the respect and obedience that we never see in his earlier life. He achieves true freedom inside bars—as a protector and the one that everyone obeys, including law enforcement.

The book ends of “Shot Caller” are letters to and from his underage son, whom Jacob bestows the responsibility of protecting his mom. The ultimate morality of this film is there is no morality except protecting women…The film never asks who they are protecting them from though the answer is clearly implied: the same men who are allegedly protecting them. Money jeopardizes Shotgun’s girlfriend’s fate and the rival gang’s wife. The Beast holds everyone’s fate in his hands. Does the film follow these women to see how they are doing? No. A film shows what it cares about by what it shows, and this morality is the veneer to act amorally without condemnation.

“Shot Caller” takes too long to make its point, and even though a handlebar mustache cannot hide Coster-Waldau’s hotness, with all the scenes in the sun, I found my mind wandering and wondering whether white supremacists used sunscreen to protect their skin. In the bonus features, Coster-Waldau stayed under an umbrella. Even the toughest guy of them all does not want a fight with skin cancer.