Hirokazu Koreeda, one of my favorite directors, directed Shoplifters, his most recent film that is now showing in theaters in the US. It is about a family at the margins of society that takes in a little girl on a cold night. The family and the girl mutually decide that they want her to be a part of the family. To call them a family of grifters would be too elevated. They may cheat the system, but in the end, the system always wins.

Koreeda’s focus has shifted to “social conscious” films. He still depicts families in an understated way, but with an implicit critique of society and bureaucracy for failing to truly care about the welfare of individuals beyond the superficial, socially acceptable surface. He has turned his sympathetic eye to criminals, whom he seems to view as the ultimate underdog, first with The Third Murder, which was flawed and one of his weakest films, and now with Shoplifters, which ties together elements from all his other films, especially Nobody Knows, Like Father, Like Son, Maborisi and Our Little Sister.

Shoplifters is no Afterschool Special in the way that it shows the family existing in the margins, but they turn their invisibility into an asset as much as possible. They are quite happy in the ways that they cope with every set back, and the set backs increase exponentially each day. These set backs are endemic to society: not enough work, no benefits, a lack of housing, a lack of love, the acceptance of abuse depending on the status of abuse. Even though the members of this family discuss themselves in a self-deprecating fashion, they are the only ones who notice, care and actively intervene to act justly albeit inappropriately. Koreeda makes the inappropriate seem reasonable and humane. Their constant hunger and efforts to satisfy it and self-soothe through comfort food is reminiscent of the constant eating of the main character in After The Storm. The real hunger echoes the great hunger that they feel to create their own societal rules, which eventually clash. They know that they are discarded, disposable and unwanted so they find a way to turn that pain into something beautiful.

Shoplifters’ way of addressing abuse is sensitive and not sensational. Koreeda has a sense of discretion in the way that he depicts brutal moments. He never shows it or limits himself to showing the moments after it happens such as oranges rolling in the street. While bureaucratic efforts for justice reduce everything to a cynical explanation of criminal behavior, Koreeda seems to prefer the individual response. There is a turning point in the movie followed by a lot of self-sacrificial acts to keep the family together, in which one character explains to the girl the difference between love and abuse. It is the most powerful moment in the film and almost deserves the Mister Rogers award or at least Moonlight’s Teresa award for explaining hard truths to the young.

It eventually leads to another character’s epiphany about the definition of abuse and exploitation and his role in inflicting it on someone that he loves. Even chosen families are flawed and have the potential to be harmful. Shoplifters explores themes of love and abuse in the denouement, which is as close to sensational as the film gets with its revelations about each character’s back story.

Koreeda is a master at the way that he depicts the passage of time either through scenery or dialogue. He gives enough detail to pique the viewer’s interest, but never feels as if he is turning a character (until arguably the end) into an exposition fairy. His films always feel as if volumes happened before the movie started and will continue long after it ended. Even though the movie is two hours one minute long, I didn’t want it to end. There is a sense of an ambiguous legacy simultaneously rich and lacking which will impact countless others in the way that the children of this family decide to keep or discard what they learned from these grifters about life and love.

Lily Franky is perfect as the imperfect patriarch of this family. He has been playing perfect surrogate dads without a whiff of impropriety since Like Father, Like Son and is a Koreeda staple though I forgot whom he played in After the Storm. Franky has to be shiftless and a bit disreputable while simultaneously seeming like a solid, caring father figure, which he makes seem easy. There is a blink and you’ll miss it scene in which he imagines a better life when he goes to work, which is heartbreaking considering the end. Ando Sakura who plays the mother and his wife also has a friendly fierceness in protecting her brood, which includes the little girl fairly early in the movie, but I never got the sense that she was superimposing her needs on to the girl. Instead her performance seemed to make her character like a time saver, delivering lessons that it took her years to learn and believe before she found happiness.

Aki’s story almost worked, but didn’t quite fit into the framework of the larger story. She is the younger sister and plays schoolgirl while other girls in the film actually are schoolgirls. After the revelation of her relationship with her grandmother, I wanted to ask follow up questions because I’m not sure if I understand her story. It feels like Koreeda will revisit a version of her story later in a separate movie. There seems to be an unspoken relationship between her story and Oh Lucy! about the need for and lack of connection and human contact, the existential crisis of identity and despair and how this gap is inadequately filled by the sex industry. While I hate the whore with a heart of gold trope, I’m not going to dismiss it as such because out of everyone in the family, she seems as if she is floundering and is looking to become paired with someone, not necessarily romantically.

In contrast, there are so many unanswered questions about the grandmother, who is played by Kirin Kiki, in her final performance, but explicit answers aren’t needed because her acting implicitly eliminated my curiosity. She got exactly what she wanted among her kindred spirits whereas in any other context, it is elder abuse. Koreeda has a talent for flipping our cynicism on its back and looking at life in the most charitable way. Side note: someone who loves him needs to watch his back to make sure that he doesn’t get got.

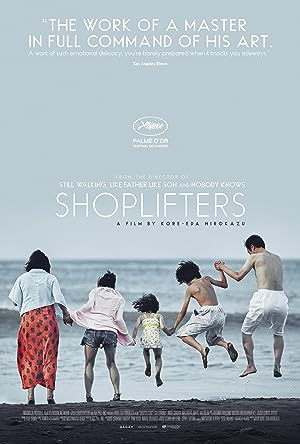

If there was one predictable moment in Shoplifters, it came soon after the beach scene, but was hanging over the proceedings like a Sword of Damocles from the beginning. I will happily sign a waiver. Apparently so will the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, which awarded the Palme d’Or to this film. For once, when I went to the movie theater to see a Koreeda film, it wasn’t in a tiny theater with a handful of patrons. What took you so long? You’re late to the party. Congratulations. Shoplifters was a beautiful, bittersweet culmination of a life of artistic excellence.