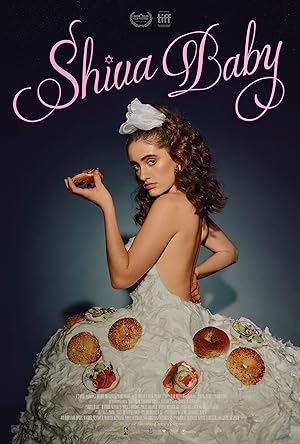

“Shiva Baby” (2021) is about a college senior, Danielle (Rachel Sennott) going to shiva, a Jewish service held after the funeral, with her parents. She runs into her ex, Maya (Molly Gordon), who is also Danielle’s foil because she seems to have her life together, and her sugar daddy, Max (Danny Deferrari), while family and friends interrogate her about her life and future. Will she be able to hold up under the scrutiny and pressure as her worlds collide?

Some movies are not for me so I cannot judge whether “Shiva Baby” is a great movie. It conveys Danielle feeling overwhelmed and trapped, but Sennott’s face was often vacant and lost, which is the point as she tries to play it straight while hiding a lot of turbulence boiling under the surface; however I found it a little too inscrutable. When the tension bubbles over, she expresses it in a desperate show of devotion and mortification, a theme of self-abasement that develops over the course of the film. Even though I grew up in Manhattan in Jewish majority communities, I missed references that I believe were significant and meaningful to the moments leading up to the denouement.

“Shiva Baby” sticks with Danielle’s perspective, and she is an unreliable narrator. The film shows and does not tell why Danielle is such a mess. (Someone needs to tell her to get the money first.) Even in the opening scene, when Danielle is at her most confident, Danielle seems to embody contradiction-revolt, attraction, pulling away then passionately unwilling to separate. I did not understand her or relate to her, but if the message was supposed to be that these contradictions reflect her confusion about what to do, who she is, then it worked, but I could not help but wonder if I was missing key elements of Danielle’s psychological profile that the film and Sennott were conveying. The film implies that she had an eating disorder, but there is something more undiagnosed and untreated in her manner. As the film progressed, she perceives the people around her as increasingly hostile and sneering. The lighting indicates when it is imagined, but sometimes it felt exaggerated, but was shot realistically so Danielle was not always imagining that these people were as mean to her as they were.

“Shiva Baby” deserves kudos for not refraining from taking the predictable beats such as the explicit confrontation between Danielle and the cheated spouse or Danielle and her sugar daddy though it comes close. The film is open ended, and considering how each character changed dramatically over the course of the shiva, anything else would feel pat. I was irritated that the film found no other way to wipe the smug look from Max’s face. I hated Max: his token lip service to women’s rights while being a person who exploits women, his undeserved sense of superiority over Danielle or that she owed details of her life to him and the obliviousness to how vulnerable he was to his life blowing up if any of the women in his life caught on. The film made a repugnant character and never redeems him, but also never rebukes him, which is realistic and frustrating. I wanted catharsis from him, not Danielle.

Maya responds in a very human, imperfect way to Danielle. I understood her contradictions more. Maya vacillates from wanting to get one last dig in to reverting back to their prior relationship status and be close to Danielle. She is drawn to her and wants to show how great she is doing without her. There is a moment near the denouement when Maya reacts in a way that shocked me, but was predictable. Based on her age—younger people are supposed to be more open minded and less knee jerk judgmental since they are at least exposed to other ways of thinking about certain topics, her savage reaction seemed unforgiveable though “Shiva Baby” disagrees. If these people are closest to Danielle and should have her back, no wonder Danielle is a mess.

The final scene in “Shiva Baby” is one of hope and community. At the end of the day, despite differences and tensions, there is an acceptance and coexistence without forgiveness or forgetting, a détente which can lead to going forward, among all the characters. No matter how outlandish a character’s behavior is, that character can expect to move forward with everyone and be cared for albeit roughly and not the way that one would prefer. It is the release from the claustrophobic internal scenes that lead to hysteria.

“Shiva Baby” has been praised for its bisexual protagonist, and indeed, no one raises an eyebrow that Danielle had a relationship with Maya, but people are constantly trying to separate the two? Is it because their relationship was so volatile or because they are hoping that they will settle down with a nice guy, which is an oft repeated phrase. There is a heteronormative default expectation, and it takes characters longer than it should to cotton to the nature of their shared past. Also I was under the impression that bisexuals are stereotyped as promiscuous and untrustworthy, which this film does not seem to challenge and frames Danielle’s job as if it is a relationship choice, not work, until Danielle explicitly explains that it is about power and money to shore up against the other inadequacies of her life. The film does explore this theme in other ways.

Danielle becomes obsessed with Max’s wife, Kim (Dianna Agron), because Kim is Danielle’s opposite in their respective stations in life. These scenes reminded me of the protagonist in “Young Adult” (2011) although Danielle is aware of her fixation. If “Shiva Baby” ever had a spin off or a sequel, I wanted it to be about Kim because if Danielle was being objective, Kim had it all, but had nothing. She created the life full of demands without any rest or consolation for her. She was complete in herself, but surrounded herself with what she wanted or thought that she wanted-a husband, a baby, a new religion and community, and was alone with no comfort. Danielle and Kim belong to the community, but as women, share a burden of inadequacy that Max seems exempt from by simply existing. I also found it interesting that Agron plays a shiksa, but is Jewish in real life and vice versa for Sennott-image versus reality and what that says about identity, especially since the writer and director, Emma Seligman, and the majority of the cast are Jewish and applaud the casting choices.

If there is one character that I would want to associate with in real life, it would be Debbie (Polly Draper), Danielle’s mom, although she is the one that puts Danielle in this situation. “Who brings a baby to a shiva?” Her impatience at her husband’s incompetence and her fumbling, earnest but boundary transgressing attempts to better her daughter’s life were endearing.

“Shiva Baby” has a setup that sounds like a sitcom, but it is more like a horror movie without anyone getting physically violent. If you suffer from secondhand embarrassment, you should probably steer clear. Please feel free to educate me on what I missed. I really enjoyed the understated short.