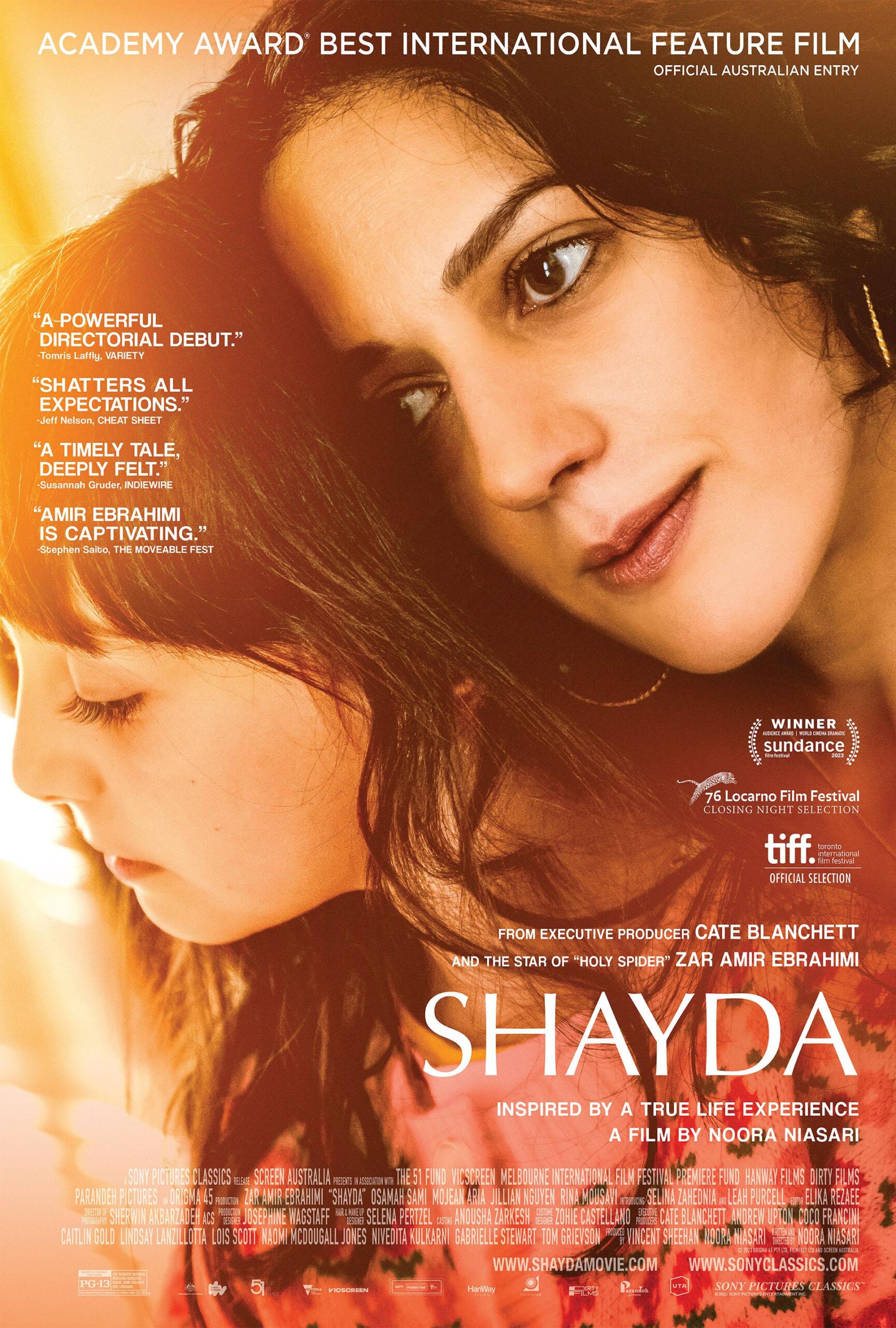

“Shayda” (2023) was Australia’s submission to the 2024 Oscars’ “Best International Feature Film” category. Executive producer Cate Blanchett would not put out mess! Set in March 1995 during the two weeks around Persian New Year or Nowruyz, Shayda (Zar Amir Ebrahimi) and her daughter, Mona (Selina Zahednia), are living in a women’s shelter to protect her from her abusive husband, Hossein (Osamah Sami), until the Australian courts grant her a divorce in the hopes that she will get custody, which would not happen if she returned with him to their homeland Iran. She wants to remain connected to her immigrant community, but she is terrified that either she or Mona will accidentally reveal the location of their temporary home and endanger everyone who lives there. When the court allows Hossein to have unsupervised visitation, that danger increases now that he has a way to interact with them.

“Shayda” is a gorgeous cinematic experience on multiple levels. Ebrahimi, who previously delivered a stunning performance as a fearless, determined reporter in “Holy Spider” (2022), is completely unrecognizable and transforms to play the titular character. Shayda starts as a furtive, closed off, shaken woman with only seeds of hope—literally and figuratively in the opening kitchen scene. Despite an omnipresent, invisible hanging sword of Damocles portending that all her attempts at escape can come crashing down, once it seems possible, Shayda gradually begins to live the life that she wants.

Zahednia may just be a child, but she portrayed Mona’s plight perfectly. With her mother, Mona feels secure so she displays a range of emotions and can frankly be an oblivious pain in the ass who begs to return to Iran or complains about food. With her father, she is silent and vigilant, terrified to step on a landmine, cognizant that her father is manipulating her for information which could hurt her mother. When she begins to act like a child around her father, she briefly forgets her situation, but it never lasts long. Even though she does not act like it when she is around her mother, she may be more terrified than Shayda.

If watching “Shayda” sounds like a depressing experience or slightly elevated Lifetime with an international flavor, dispel those notions immediately. If you think that you know what to expect from a movie predominantly set in a women’s shelter, you don’t. There is no support group platitudes or vacuous, saccharine sentiment of sisterhood. Oftentimes the fellow residents seem to pose a threat, and a woman in the next public bathroom stall or grocery aisle could be a snitch. Internalized misogyny is a subtle force, but a complicating factor, which forces each character to evaluate others on their own merits. Any solidarity gets earned over time and not without speedbumps. Joyce (Leah Purcell) is the stabilizing center of the home who works with the residents and acts like the barometer to judge others against. She illustrates the difference between laughing with you versus laughing at you. Entitled residents Cathy (Bev Killick) and Renee (Lucinda Armstrong Hall) reflect the latter and exhibit resentment against Shayda.

Because “Shayda” is set during Nowruz, which would be springtime in Iran, but in Australia, the season is fall, the environment is illustrative of Shayda’s mixed emotions about leaving her husband. On one hand, she loves the safety and freedom, which is symbolized with a dancing and makeover theme, but on the other hand, she is still living in a grey area and in exile from her community. The lighting is often warm and red to symbolize the celebration, but in moments of tension, the lighting is colder, especially at the mall where the visitation drop-off happens. Using her mom’s story and implicitly her childhood as inspiration, writer and director Noora Niasari depicts the complicated dynamic of being an immigrant in a foreign country who expects and often receives disapproval from her community for leaving her husband. Shayda and Mona cannot even rely on comfort food because it is only available at the Persian Market, which could lead to others following and discovering her location then giving it to her husband. Also because the food is imported, it can be expensive so Shayda is not able to afford it thus engage in certain practices Eventually Shayda begins to trust an old friend, Elly (Rina Mousavi), which felt a little underdeveloped, and Elly’s Canadian cousin, Farhad (Mohean Aria). Shayda’s interaction with this man elicits further disapproval from her community, but it is also functions as a nice counterbalance to Hossein’s negative image, which could perpetuate biased views that all Middle Eastern men are abusive.

Before Farhad comes on the scene, the other shelter residents are shown engaging in romantic relationships. Just when Shayda begins to bond with them, Farhad feels like an interruption to that dynamic, and the idea of a romance being plopped into the middle of this character driven drama had the potential of being repugnant, but it works because it is so modest and innocent. They hang out at libraries, walk, and talk often in groups. These moments provide insight into Shayda’s past and how systemic sexism altered the trajectory of her life thus exacerbating the inevitable dissolution of her marriage. Their burgeoning relationship is such an innocent slice of wholesome goodness that it stays in line with the understated narrative that could have been overwrought and melodramatic. Ultimately Farhad’s primary function is not as a love interest, and the film’s agenda is flawed and two-dimensional, but I will sign a slight waiver because it is Niasari’s debut feature, and she can be forgiven for trafficking in a trope during the denouement.

Hossein is a standard textbook abuser, and Sami stops short of chewing the scenery. Anyone with experience in dealing with these types of people will spot him coming a mile away, especially in the way that he talks and acts like the aggrieved party, and everything is about him. Barely restrained, seething, frustrated fury is the best description of his manner. He knows that he should be on his best behavior, but he cannot resist invading Shayda’s space and prolonging their conversation. He arrives late then complains about the amount of time that he gets with his daughter. He promises to be better but cannot even model his ability to fulfill empty promises in the present. He never gives his full attention to his daughter to get to know her, and he only wants Mona to give him affection, “It’s only about dad,” or an oldie but a goodie, guilt-tripping, “Don’t you love me anymore?” Parents, not children, are supposed to be the givers. It is not long before his veiled digs are overt, and he becomes threatening, controlling and hostile. “I just want us to be together again.” Um, then when Hossein is with Shayda and Mona, he should not make it the most awkward and uncomfortable scenario. Dude could not love bomb to save his life. Niasari gets viewers invested in Hossein’s well-being because the sooner that he graduates, the sooner that he will return to Iran then Shayda and Mona would be safe.

“Shayda” ends a year later and reveals where Shayda, Mona and Hossein landed in their legal battle. It is an idealistic albeit realistic happy ending though not the one that they would wish for themselves. Niasari’s first film is a resounding, relatable film that mostly avoids the pitfalls of domestic abuse dramas, and is a stellar example of how to portray survivors in a dignified, humanistic, insightful way.