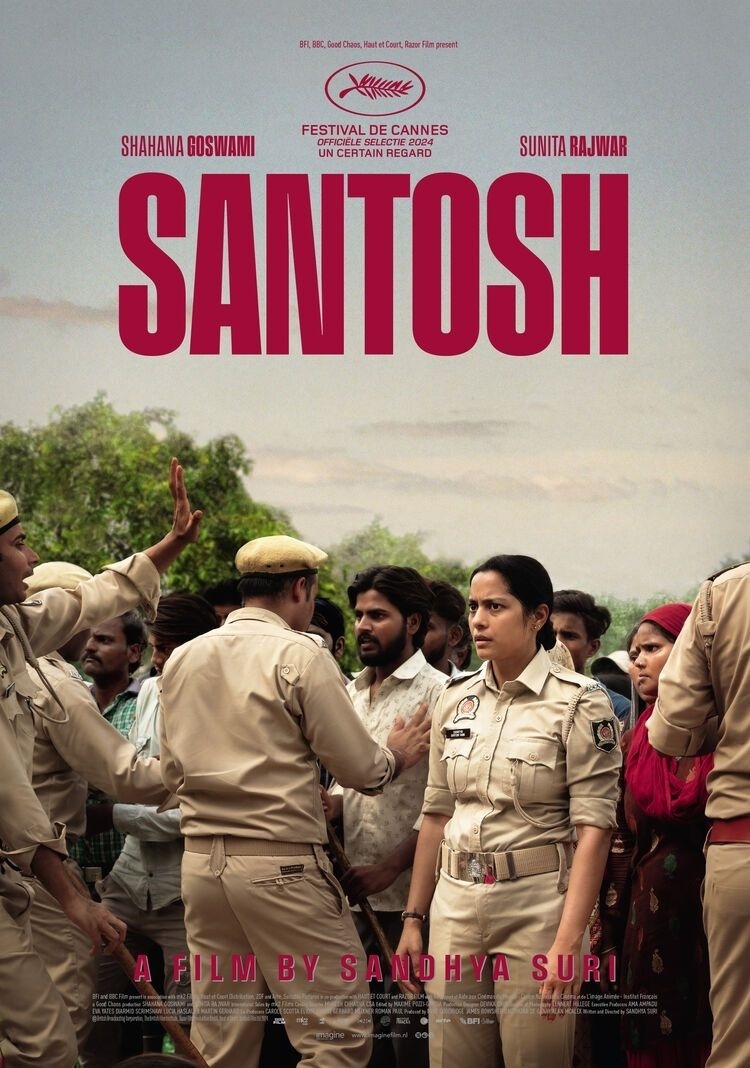

“Santosh” (2024) refers to the first name of a widow whose husband was a police constable and died on duty. Left with little income except for her husband’s pension and no housing since her apartment was a benefit that came with his job, Santosh Saini (Shahana Goswami) decides to inherit his job thanks to a recent law, which will offer her pension benefits, a salary and a residence. She gets assigned to a locality in Northern India, a rural area where she learns on the job. She becomes invested in her job when a thirteen-year-old girl goes missing and is frustrated at how no one takes the crime seriously. When a new police chief, Geeta Sharma (Sunita Rajwar), is assigned to the job, Santosh feels seen, and her job becomes an apprenticeship, but should Santosh emulate how a woman chief operates?

“Santosh” is a character study, a police procedural and a window into how the flawed world functions. The protagonist moves from mourning, trying to survive, striving, experiences a crisis and ends in a way that feels like a full circle except with more knowledge about herself, the world and the chasm between hope and reality. There are no Hollywood endings or inspirational moments. It is all gritty realism with some pulled punches. When introduced to Santosh, she is an unconventional character who married for love. She additionally enjoyed the freedom of having a spacious apartment with her husband. The prospect of reverting to less puts salt on the wound of loss. While she loves her parents, she does not want to go back home and is eager to be independent.

When Santosh chooses a male dominated profession in an unfamiliar place, Goswani plays up her discomfort and deference. Santosh is shocked at how women in her line of work act: curse, intimidate men, possess a little power. She is testing the limits of her job and hopes to make a difference, but crashes back into reality when her boss, Inspector Thakur (Nawal Shukla), cares more about the job’s perks than his duties. Santosh is not an idealistic, wide-eyed innocent. When a protestor slaps her, she slaps her attacker right back with no fear of repercussions because of her position. Not turning the other cheek may be police brutality, but it is also a perk for a woman who has been suppressing rage about her circumstances and her husband’s unsolved accidental homicide. Her inner compass is not fixed.

If “Santosh” was a Hollywood movie or a television series, Geeta’s story arc would be different. Gender does not equal justice, but it does mean there is an opportunity for Santosh to get the case of the missing girl taken seriously. Geeta critiques the way that things have been handled, implements some reforms such as not having to pay to have a police report written and wants people to do their jobs, not just accept bribes or loaf around on the job. Some parts of the job do not change like sexist jokes or some unethical practices, including not respecting jurisdiction, manipulation and police brutality. Geeta is first depicted as some random woman occupying a communal shower who does not jump when Santosh interrupts her. With or without the uniform, Raiwar plays Geeta as a confident woman who knows how to navigate the world even naked.

The effect of Geeta’s mentorship on Santosh is almost instantaneous. Santosh’s bearing and pride are more apparent. Geeta motivates Santosh’s investigation by conflating it with her husband’s unsolved death. If “Santosh” is unusual, it is the fact that none of the police walk around with guns, including the women, and they do not always have partners accompanying them. The unspoken tension lies in the fact that they are investigating the unsolved rape and murder of a missing girl, and these two women who are also law enforcement officials can easily switch places with her, but they show little to no fear and take huge chances to track a suspect.

Santosh discovers that closing one case does not solve systemic problems and reveals new ones. As Santosh moves up in the ranks, British Indian director and writer Sandhya Suri, a documentarian in her fictional feature debut, which coincides with Indian filmmaker Payal Kapadia’s similar career trajectory, omits scenes of public relations glory and emphasizes the microcosm of disrespect: a chair removed, a newspaper with a photo of her face dirtied, etc. Also, as Santosh achieves professional success, there are fewer scenes showing her mourning her husband. Suri’s sense of color and framing is almost painterly. In the opening scenes, it is night, and there is light, but Suri chooses to show the flashes of color with Santosh’s clothes and the sound conveys the danger of oncoming traffic. Later only interiors are similarly dark or tenebrous because of the lack of reliable electricity. Santosh’s signature colors are deep blues and aquamarine, but in her official capacity, she wears an official tan uniform cut like the guys. There is a tunic option for women that Geeta and Santosh forgo. These stylistic choices portend their style of working—they will imitate the men in their official capacity.

When Santosh achieves a certain level of status and respect in her profession, she reevaluates whether she achieved the goal that she originally wanted. While the lessons that “Santosh” delivers are far from subtle, they are worth repeating. Power perpetuates itself even when the person who possesses it changes. Did she change the system or did the system change her? At one point, Geeta asks Santosh, “How can you move on in life without justice?” The movie offers no pat answers, but Santosh stops suppressing her grief with usefulness, achievement and power. She returns to herself and stops running away from the pain. She also acknowledges that the pain that she feels is the pain that she inflicts on others whether she intends to or not.

It is easier to make someone else a monster than to confront the monster inside oneself. The dance between privilege and oppression is an uneasy one. For American moviegoers, a lot of the meaning in “Santosh” will be lost in translation. There are themes about caste, religion (Muslim vs. Hindu), regions, etc. that is not something that will be easy to pick up on. What is the significance of the nose ring? People who saw “Origin” (2023) will have an advantage and recall the plight of the Dalit people.

The United Kingdom submitted this Hindi language film to the 97th Academy Awards for Best International Feature Film. “Santosh” opens in India on January 10th. It is interesting that the Indian diasporic film casts a cynical eye on India whereas Kapadia’s film pulls no punches and has a balanced and sometimes Edenic view of her homeland. It would be interesting to see how this film is received in India. People who immigrate are naturally less attached to their homeland and feel forced to leave so it could color the way that her creative work depicts that place. Perhaps it explains why “All We Imagine as Light” (2024) is more critically acclaimed despite neither France, which submitted “Emilia Perez” (2024), nor India, which submitted “Laapataa Ladies” (2024), chose it to represent their country in competition for the Oscar in the same category.

It is unfortunate and perhaps a skosh biased that “Santosh” is being compared to “All We Imagine as Light,” a more modest, human story that soars because of the resonating intimate emotions that it depicts. These two films are the cinematic equivalent of apples and oranges. It makes more sense to contrast a film like “Wicked Little Letters” (2024) with “Santosh” (2024) which are based on true stories. While both films follow familiar trajectories, “Santosh” has gotten more flack for being predictable even though the prior film is so wedded to the commercially acceptable mystery and is a feel-good movie.

“Santosh” is a feel-bad movie that drags a bit at times. It denies the audience pat solutions or pat boxes to place people as villains or heroes. If it is predictable, it confirms truths about the way that the world works that feels hammered home because of lived experience, not the movie being repetitive or overstaying its welcome. If you are expecting a satisfying mystery where two plucky women show the guys how its done, you will get that, and you won’t. Women are human beings, and human beings are flawed. It is misogynistic to expect better just as it is harmful to expect worse from one gender for belonging to that group.