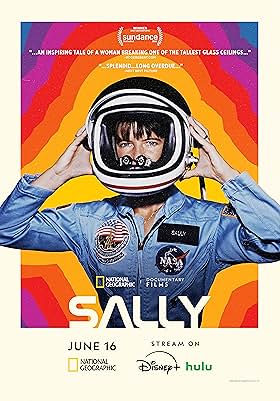

“Sally” (2025) is a deeply conventional documentary about an unconventional woman. What does a woman who braved sitting on top of 7.5 million pounds of flammable propellant, going to space and being outnumbered by men fear? Being outed as a lesbian. Director and cowriter Cristina Costantini and cowriter Tom Maroney make a riveting biography about tennis player, physicist and astronaut Sally Ride, the first American woman who went into space on June 18, 1983. While it cannot always sustain its momentum, it never crashes.

Costantini and Maroney use archival audio of interviews with Ride, exclusive interviews with people who knew Ride and the occasional talking head, archival news footage, press conferences, media appearances and recreations without showing the actors face shot in the style of the era complete with the flaws that come with switching spools of reel and glitches on the frame. “Prime Minister” comparatively felt monotonous because the previously aired footage dominated the movie whereas in “Sally,” there is a contrast between Sally the professional with her coworkers, a seemingly media trained Sally, the inscrutable private person and the woman who could be herself in select spaces with a handful of people. It is like getting a sneak peek behind the curtain into a world that most of us would otherwise never know. Like “Hidden Figures” (2016), it is tantalizing look at the real people behind the scenes.

The lead interviewee is Tam O’Shaughnessy, a childhood friend, committed life partner of twenty-seven years and cofounder of Sally Ride Science at UC San Diego, a STEM nonprofit. Based on Ride’s legal actions prior to her death—they could not marry because the Supreme Court of the United States had not issued the Obergefell v. Hodges decision, which nationally legalized same-sex marriage, O’Shaughnessy is authorized to tell Ride’s story. O’Shaughnessy is the opposite of Ride as someone who spent most of her life openly gay and deeply wounded at the restriction of being in a relationship with Ride, keeping their love a secret. In retrospect, it is obvious how visibly it pained her to be in public without being herself and showing affection to the woman that she was in love with. Molly Tyson, Ride’s college girlfriend, also shared about her closeted relationship with Ride though Tyson was also an out and proud lesbian, but never could talk about anything other than their friendship.

The interviews with her astronaut colleagues start off as fairly standard, but as they continued, it becomes obvious that Ride was not at NASA to make friends. It was the first unofficial reality television. Kathy Sullivan from the Class of 1978 seemed to get the brunt of Ride’s competitive nature and theorized that Ride sabotaged one of Sullivan’s assignments. John Fabian from the Class of 1978, who was also selected to go to space with Ride, suffered no such concerns and just considered her fun to work with. Steve Hawley from Class of 1978 found her remote, which is surprising when it is later revealed that they got married and was one of the last to know that his wife was a lesbian. Anna Fisher from the Class of 1978 joins Sullivan to describe what it was like as a woman astronaut to experience incessant media scrutiny, attempting to adhere to male appearance standards to fit in, which was characteristic of Eighties fashion, and concurs that Ride couldn’t befriend her competitors—implicitly if they were women. They also discuss Judy Reznik, who competed against Ride for the first-place position, died in the Challenger explosion and appears in the footage. Mike Mullane from the Class of 1978 is the only one who is willing to paint himself in a frank, but unattractive light with his forthrightness about his chauvinistic attitudes, but it is a fair note that as a Vietnam era veteran, if they were men, he may still have turned his nose up at them as being unqualified, which is never explored.

Unbelievably, Joyce Ride, Ride’s mother, is still alive, and though she participates in the interview, she seems appalled that Costantini, who can be heard asking questions, expects her to answer. “If I knew how I felt about feelings, I probably wouldn’t tell you.” Many of “Sally” participants theorize that even though her upbringing was perfect to nurture girls to excel, it left her stunted as an expressive person. In contrast, Bear, her sister, really fell far from the tree. Even at the risk of her career, Bear came out first and was open about her romantic relationship, but she refrains from disclosing how she felt about Ride subsequently avoiding her, though O’Shaughnessy was horrified considering that she knew the truth about Ride.

There are also interviews with feminist “20/20” journalist Lynn Sherr, who covered Ride in the media and was a personal friend unaware of Ride’s sexual orientation, and Billie Jean King, another former friend who met Ride when Ride was a counselor at Tennis America at the Incline Tennis Club on Lake Tahoe, which King cofounded with Dennis Van der Meer, a famous tennis coach. If you are unfamiliar with the era, most of the time, the interviewees’ discussion of their experiences offers sufficient context, especially King suggesting that Ride decided to remain closeted after seeing how King had to start from scratch once publicly outed. Though most of the film includes people who personally knew Ride, the only exception is Margaret Weitehamp of the National Air and Space Museum who describes American women’s earlier attempts to become astronauts, explicitly Jerric Cobb, a renown aviator. Weitehamp also reveals that women physically test better than men in cardiopulmonary and sensory deprivation.

It is an interesting time to release “Sally.” NASA probably would be unable to explicitly diversify its ranks if they tried today. Will this history be officially erased? This progress was so brief, and it could be over. O’Shaughnessy describes NASA as deeply conservative, “If you’re queer, get out of here,” which Ride’s partner also claimed did not bother Ride, but upon returning from space, the strain of the double life becomes visibly apparent and explains why she walks away from NASA and her marriage though it would take facing her mortality to make her come out of the closet. Unfortunately, as the gap between her public and private image narrows, the story starts to drag. If it was not a complete biography and just focused on the beginning of her romantic relationship with O’Shaughnessy, it could have maintained its pacing, but Ride’s gradual disillusionment and O’Shaughnessy’s distress at consenting to a double life makes it harder to watch without feeling secondhand sorrow, which shows how effective Costantini is at conveying real life stories.

With “Sally,” Costantini and Maroney have the benefit of reflecting on an era that is far enough away from the present that looking back does not feel premature. It also does not feel redundant thus making archival footage feel like unnecessary repeat programming. The story is close enough in time to feel familiar and comprehensible. It is a nostalgic walk down memory lane for a brief time when the US just seemed to finally be moving forward, a progress that slowed until it halted completely.