“Rustin” (2023) refers to Gandhian nonviolent civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, a pioneering Black, gay man who lived during a time when being gay was criminalized or deemed a mental illness and later died happy and in love during a time when marriage equality did not exist. The dramatization starts in 1960 at his professional nadir when his colleague and friend Martin Luther King, Jr. bowed to threats and failed to stand beside Rustin which led to Rustin’s temporary exile from the movement. It then chronicles his return and the culmination of his career as the mastermind of the iconic August 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

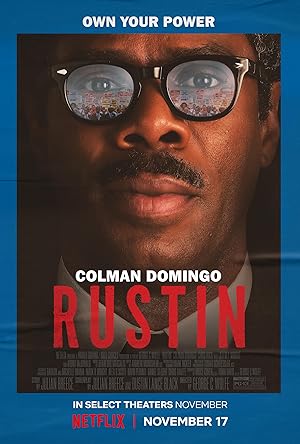

Colman Domingo, who often plays charismatic conmen in “Fear the Walking Dead” and “Zola” (2020), dominates as the titular historical figure. “Rustin” is an uneven movie, but Domingo carries it kicking and screaming on his back into rising above television movie status and feeling like a Broadway play brought to the screen; however, the screenplay was not adapted from the stage, but the result of writer Julian Breece conducting two years of research with Rustin’s real-life friends and professional associates. Domingo’s commanding performance and quotes from the real-life Rustin make the movie better than it is. The history is so innately emotionally resonant that it would take a lot of effort to make it devoid of value.

Few actors can hold their own in a scene with Domingo. Glynn Turman, who plays labor unionist and activist A. Philip Randolph, one of Rustin’s loyal supporters, brings at least six decades of acting under his belt and carries enough gravitas. TV character actor CCH Pounder has a brief supporting role as Dr. Anna Hedgeman, and “Rustin” makes space for the character to point out the misogynoir embedded within the March’s programming. Michael Potts puts on a decent Jamaican accent as labor organizer and activist Cleveland Robinson. The underutilized Audra McDonald plays Ella Baker, who ends up being reduced to a gossiping girlfriend, which was refreshing after hearing so much dialogue that sounds more like excerpts taken from speeches, but Baker was also an expert organizer. It will surprise no one that Jeffrey Wright makes the most out of his brief appearance as Rep. Adam Clayton Powell, a villain in the film who uses homophobia to divide the movement and play a bigger role. Carra Patterson injects some life into the film as Coretta Scott King in a depiction that shows more than it tells how the wife sacrificed her talents and career for others.

“Rustin” featured flashes of notable actors who barely got any screentime so it would be unfair to judge a performance based on a second, but stunt casting Chris Rock as NAACP Roy Wilkins was a big mistake. It is unclear whether it is too soon after The Slap or whether Rock’s quality of acting is to blame, but he fails to disappear in the role and does not fit in a film that works hard to recreate the era and erase any trace of contemporary life. Many actors play notable historical figures such as Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Whitney Young, Medgar Evers, James Farmer, but they would have been otherwise indistinct if it was not for a flash of captions indicating their name and association. Aml Ameen who plays King with a certain reticence almost vanishes in Domingo’s presence instead of seeming like his complementing equal. Johnny Ramey plays Rustin’s closeted love interest but fails to inject any eroticism in his performance other than some coy flirting. Gus Halper does a better job by making sure that his eyes are welling up with tears even when he does not have lines in scenes or appears briefly on screen, but his character, Tom, another closeted love interest/assistant, also sounded more intriguing and less cliché as a white man who abandoned privilege for principle.

“Rustin” improves as it unfolds, but it is a slow burn of a movie. The narrative suggests that Rustin envisioned the March uniting warring forces in the movement. It starts with Rustin seeming washed up and irrelevant to a group of fractious younger people, who gradually becomes his most stalwart followers, but Rustin proves that he still has the spark of creation within him. As the story unfolds, the youthful energy of the activists managing the logistics evokes the vibe of a devoted class surrounding a college professor or a bunch of theater kids getting ready to make a show. When Powell challenges Rustin before the March, they embody the imagined nonviolent peace army that would defend the “society of peace” that Rustin wanted.

“Rustin” also does a deft job of underscoring the importance of gospel music to Quaker Rustin as “exalted rage.” This concept is a seed when he resigns from an activist position that demands that he erase his Blackness. As Rustin faces harassment with repeat phone calls at home, he blasts Mahalia Jackson’s records as a balm. It results in a climax of Jackson (“The Holdovers” Da’Vine Joy Randolph) performing at the March.

“Rustin” manages to convey the appeal of peaceful protest in an era when fighting back is a more instinctual, human option. The black and white flashback of Rustin sticking by his principles while being beaten later followed by a room full of black NYPD cops disarming themselves seem more forceful than the opening scenes recreating classic civil rights moments immortalized in photographs and archival photographs. The PTSD scenes combined with his involuntary radio outing creates a relatable empathetic atmosphere that evokes the pain and strength required for Rustin to sacrifice his well-being for those who refuse to return the favor.

The story needed to be tightened up. “Rustin” opens with heartbreak then later Rustin explains how he felt in that moment as if the audience needed to be reminded. Similarly, Rustin mentions his first nonviolent moment and the brutal beating, which the movie later shows. Only the latter scene was needed. When Rustin gets an unexpected phone call from a rival, that moment gets repeated with a park breakup. While both scenes serve slightly different functions, it is still redundant outside of a television series with twenty-two episodes.

Director George C. Wolfe’s vision of 1960s Manhattan was period perfect, but the camera movement and editing were other uneven elements. It felt as if he wanted to echo the exuberance of a musical, but it resulted in chopping up Domingo’s scenes before a viewer was done savoring the moment. It did not quite work, but it could have. The Washington DC green screen scenes are painful and amateurish.

“Rustin” works because of what it evokes, not how it executes it. I found it meaningful because it was set in Manhattan. Rustin’s death from a ruptured appendix coincided with the AIDS crisis stripping the world of elder gays and leaving a void of wisdom and excellence that left younger generations without guidance. This world creates an ahistorical fiction that pretends that people such as Rustin never existed by erasing them from history or the world. This movie does its part to right the scales.