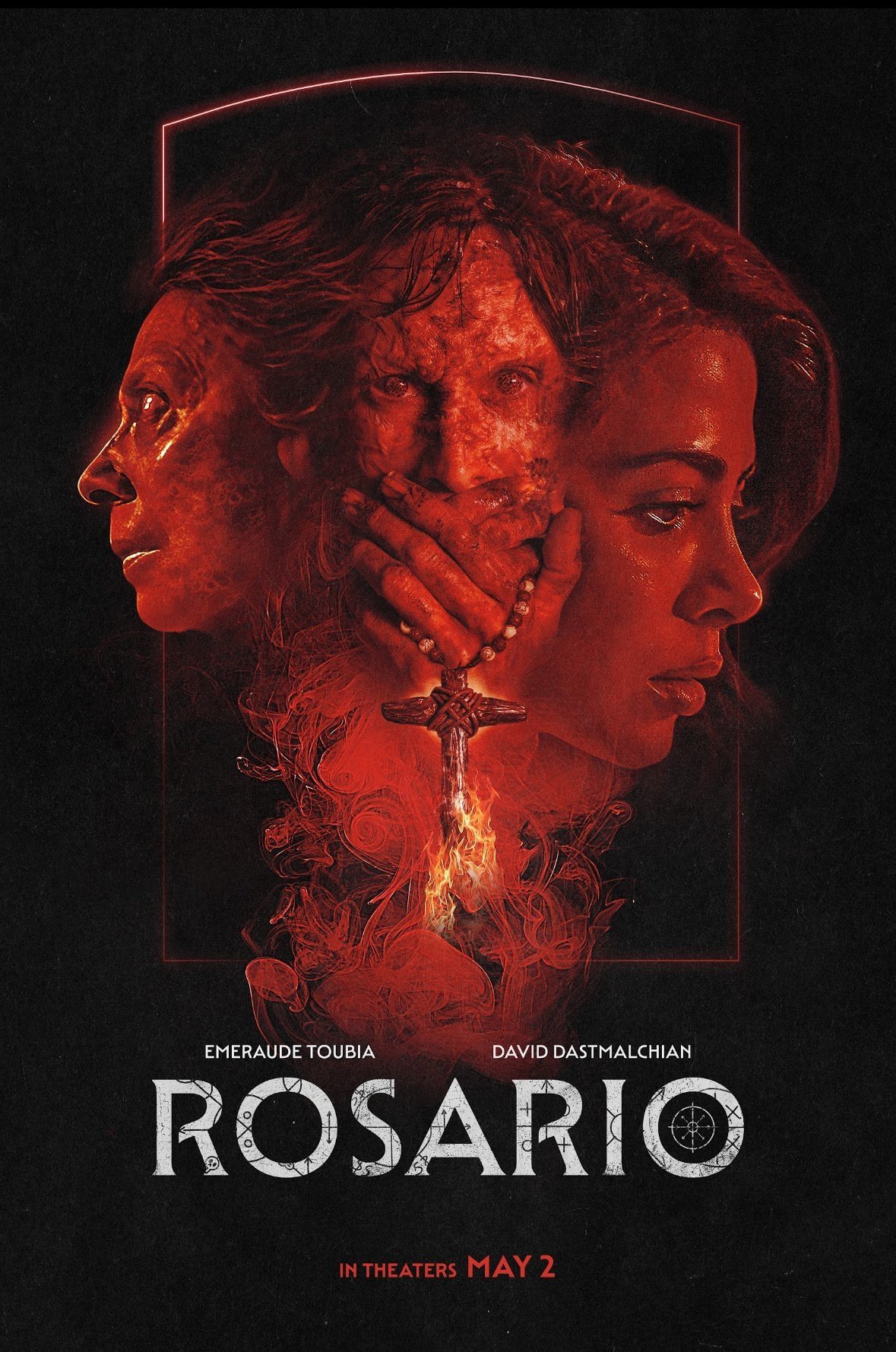

“Rosario” (2025) is about the titular first-generation Mexican-American woman (Emeraude Toubia) who achieved the American dream and calls herself Rose. Her family sacrificed so she can have a better life. Dad, Oscar Fuentes (José Zúñiga), worked long days in a factory alongside his ailing wife, Elena Fuentes (Diana Lein). Abuela (grandmother in Spanish), Griselda (Constanza Gutierrez), watches her granddaughter get inducted into a faith that she does not share at the first communion in 1999. Because abuela was undocumented, when she dies, Rose stays with her body, so it does not get lost. With a storm delaying the pick-up of the body, Rose ends up staying longer than expected, and strange things happen. What is the price of the American dream and is it worth it?

Toubia appears in almost every scene in “Rosario,” and her strong performance anchors the movie. In a twenty-four-hour period, Toubia is convincing as the adult version of young Rosario (Emilia Faucher), who looked out her grandmother’s window at Manhattan dreaming of one day living there. From her wall-to-wall window, minimalist, contemporary apartment to her daily diet and exercise regimen, Rose lives a perfectly assimilated life until she gets to work where she is torn between rejecting microaggressions from Alex (Nick Ballard) to showing allegiance through kindness to the doorman, Miguel (Guillermo Garcia). The high-stakes stress of her job in finance affords her some protection, but the minute that she hits the streets and the subway, the trappings of her privilege do not protect her.

This directorial debut for Columbian Felipe Vargas wisely emphasizes that transition when he takes time getting her reacclimated to her grandmother’s surroundings before jumping into the spooky territory. Rose is out of practice dealing with ordinary people like the super, Marty (Paul Ben-Victor), and the across the hall neighbor, Joe (David Dastmalchian), so she is taken aback by their strangeness, but not as much as when she spends time with abuela’s already discolored body then walks down the hallway to the bedroom.

At this point, Vargas dives feet first into body horror, but do not think David Cronenberg. Sam Raimi’s “Drag Me to Hell” (2009) and “The Evil Dead” franchise appear to be inspirations. Vargas so favors disorienting camera angles that Dutch angle shots will not do. Some scenes are shot with the action unfolding horizontal to the camera, so the viewer is as disoriented as Rose. Entering her abuela’s space feels like entering another dimension, and it starts as early as 1999 and the subway. Prepare to be grossed out with creepy crawlies, bodily fluid and lots of bodily wounds. And that is before a disfigured corpse with long fingers arrives to taunt poor Rose, who is already feeling guilty about not going to grandma’s house more often. There is some innate horror over death, aging and the quotidian neglect that comes with living alone and sliding into filth and squalor. When Joe asks for an air fryer back, you’ll think, “Dude, you do not want it.”

The mythology of “Rosario” stands out, makes it fresh and stems from the practice of Palo or Palo Mayombe, a syncretic religion that combines Catholicism with Spiritism and traditional Kongo religion. A movie always gets extra points for not trotting out the same worn horror mythology. Because the story is told from Rose’s point of view, and she is filled with guilt, she immediately assumes that this practice is terrifying and evil, but everyone, from her dad to Joe, believe that her grandma loved her. To survive the night, Rose must take a literal crash course in the faith of her family. Even though no one should confuse a trip to the movies with a course on religious studies, no one is walking away from this movie with a clear idea of how it works because it is too much fun to make the other stay scary. Writer Alan Trezza vacillates between making this faith into a litmus test of embracing Rose’s roots and a cautionary tale that makes it seem evil. Trezza also seems to embrace Raimi’s once doomed, always doomed scenario, and no amount of pluck and courage will get Rose out of the mess. Trezza is like “The Lord of the Rings” of horror—too many endings, and he cannot decide where he wants to land. For this movie to soar, he needed to land. Ambiguity does not work here, and the end does not feel like one.

Like “It Lives Inside” (2023) and “The Moogai” (2025), the monster seems to exist to jolt the protagonist out of assimilation and internalized racism, but “Rosario” is closer to “Frewaka” (2024) because the horror is more rooted in epigenetic trauma—a person inherits their grandmother’s trauma. Three generations of women who knew and loved each other were alone in their fears and desires isolated from each other in a bid to protect their loved ones. It is like a nightmarish Gift of the Magi with survivor’s guilt ripping them apart from the inside out, and there is no way to stop transmission of the virus. This isolation makes Rosario feel as if they hated and resented her. The opening scene does feel as if she is not far from the mark when mom basically coughs in her daughter’s face and chides, “Dream on your own time.” Damn, she is a kid, not at work.

There is a paradox of love: wanting the best for your children and acting resentful when they get it. The weight of other people’s hopes and expectations is a tremendous burden for Rosario to carry, but if her genes transmit trauma, they also transmit knowledge. Rose’s clothes and accessories show how she transforms into Rosario, including having her coat ripped from her, but she is not left out in the cold. She chooses to wear her grandmother’s mantle figuratively and literally faster than anyone else would or could under the circumstances (yes, it is a movie). She claims her inheritance.

Even though there is no reference to the pandemic, “Rosario” felt like a Covid movie, especially with all the coughing, the inability to get basic services, people being left to rely on each other, the prevalent sound of ambulances. The film never explicitly states it, but the burden of climbing the ladder of success is constantly having to climb down it to try and help the people that you love. Once Rosario loses her driver, Scott, and the outer trappings of success, she is still in that body that symbolizes other to everyone because she is a woman and Latino and does not innately command respect, kindness or deference. Cell phones are the last totems of privilege and losing their charge in films like “The Surfer” (2024) means losing everything. Even if she did not feel guilty for being distant with her grandmother, everyone else will instill that guilt in her, take her down a peg or not respect her boundaries except for her father, which is another kettle of fish.

“Rosario” is a solid first feature, and if you critiqued “Sinners” (2025) for the lack of Latino representation, then here is your chance to support a Latino film with your dollars, time and attention. If Trezza had interwoven dad’s story more throughout the film instead of going for M. Night Shyamalan eleventh hour reveals, this film could have stuck the landing. With a little more work, less fear and more reverence, the Palo mythology could have been conveyed to a whole new audience instead of a scare factor. It is a missed opportunity, especially since this may be the first on screen depiction, but not an unforgiveable sin.