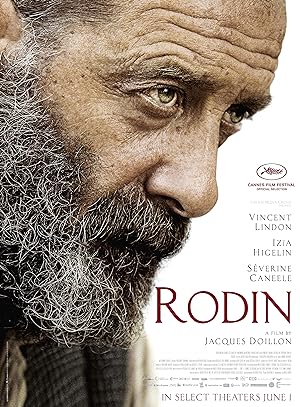

Rodin is a French movie about Auguste Rodin in his 40s when he began to reap rewards for his work. I saw Rodin at home before I saw At Eternity’s Gate in the theater, and the movies have similarities, but I loved the latter and struggled to stay awake during the prior. Does the big screen make a difference? Both movies have intervals of darkness like acts in a play while the voice of the actor playing the artist reads the artists’ words before the movie opens once again on the artist in his world.

Maybe my familiarity with and adoration of Vincent Van Gogh primed me in a way that Rodin couldn’t because while I know his work, I know very little to nothing about his life. Van Gogh’s philosophizing stems from the head and the heart then soars to the heavens whereas Rodin, based on this cinematic depiction, is more earthy and fleshy. The camera occasionally represents Vincent’s point of view whereas the camera only observes Rodin, but never shows what the world looks like to him. At Eternity’s Gate is about the artist declining as his work is just beginning to gain traction whereas Rodin starts with the titular artist at the beginning of his ascent as an art world rock star. Ultimately I would rather brunch with Vincent than Rodin, who may have loved art, but seemed to be doing it to get groupies. Is that too reductive? I don’t care.

I was initially thrilled to see women in the studio as equals in the nineteenth century. There is an unexpected modern sensibility to the interactions, and I was excited to see his daily routine in the studio, i.e. his office, as assistants, artists and models circulate in the vast space, but it turns into a stage for tedious, unremarkable trysts. It abandons its musing about art and collaboration fairly early and becomes painfully melodramatic as his most committed love affair with fellow respected sculptor and former pupil, Camille Claudel, goes south because she wants a commitment, but he refuses to leave his common law wife because she was with him when he was not a success. To be fair, he feels somewhat guilty because Claudel’s career never takes off as it should. I knew nothing about her before this movie, and I still don’t. He tacitly understands there is a double standard in terms of acceptable behavior and how it affects the reception of their work.

Rodin is definitely more French than At Eternity’s Gate, but to be fair, Vincent was a foreigner in France. Rodin cares more about love and love affairs than what made the artist famous. He happily ditches adulterous monogamy for random, frequent hookups to the delight of his common law wife because she gets security instead of a rival for his soul. The film imagines that his art is simply an extension of his libido, his obsession with flesh, a thin veneer to see nudity and feel it even if only in a different medium if a woman is not readily at hand. His compulsion does not reside in art, but what lies between his legs.

If you thought that he had commitment issues with women, then you would hate to be his kid. The film is far too diplomatic in the way that he addresses his fear of children, especially giving them his name. The fate of his children with Claudel got lost in translation for me, but she was not happy. He is a narcissist who has finally achieved glory and does not want any second hand glare from the spotlight to hit his progeny. If you never marry anyone, then you get to keep your name and all the attention. His children were hostages to his ego and approval.

The best scenes in Rodin is when his path crosses other notable figures like Victor Hugo, Cezanne or Monet, or we get to see him work on his most famous pieces such as The Gates of Hell or The Burghers of Calais. It vaguely reminded me of Andy Warhol’s factory. The work that gets the most in depth cinematic treatment was his statue of Balzac, and I momentarily got excited that the movie would continue to provide more insight into his vision and the reception of his work, but no.

Apparently the filmmaker was trying to convey that Rodin transcended class barriers with his talent, but that point eluded me. I wonder if other messages were lost in translation or if my distaste at the man depicted on screen clouded my reception of the film. It didn’t help that there were problems from the moment that the movie started. I would ask all filmmakers who convey important plot points through writing to please look at those scenes on the small screen because it was too small to read so either it would be better left out or at least use a larger font.

I would love to know if ardent Rodin fans think that this film did a great job because as an acolyte, I felt my interest diminishing with each passing minute until I completely regretted putting the film in my queue in spite of lackluster reviews. It made one worst movie list for 2018, but I ignored it because I liked some of the movies on that list (Breaking In, Peppermint and Venom), but there was enough truth on that list that I should have heeded its warning. Also a few enjoyable popcorn movies that know what they are and deliver should probably not be grouped together with an art house French film under any circumstances. It speaks poorly of Rodin because no one watched those three movies expecting that much whereas the bar was higher for Rodin even for a viewer with no expectations or assumptions.

I ended up leaving the film thinking less of Rodin than when I started. I could be a philistine, or the movie was not that good. Either way, I’ll never get those two hours back, and I should have given in to the excellent sleep that I kept trying to shake off. I left with no desire to learn more about the man or his unfortunate pupils and apprentices. At least he wasn’t a deadbeat pedophile like Gauguin.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.