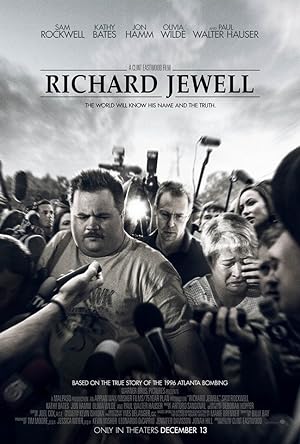

Richard Jewell is Clint Eastwood’s latest movie about the man who stopped a domestic terrorist attack during the 1996 Olympics then was considered a person of interest as a possible suspect and would later be exonerated, but not before the media and FBI disrupted his life. I do not pay to see Eastwood’s movies because I do not want to finance his politics, and his movies are deft at hiding his agenda, but he generally makes solidly entertaining films so I always put his films in my queue and watch them at home. My mom loved the movie.

Richard Jewell is several movies in one. It is primarily an odd couple movie that rests on the strength of the relationship with Jewell and Watson Bryant. It is a brilliant way of framing Jewell to not look at him through biased views about men who with live with their mothers. Instead we see him through Watson’s eyes as opposites, and Jewell may seem bumbling, too extra and inept, but he is perspicacious, hard-working and cares about the people in his life even if they do not return the favor. By defining him by this relationship, even one that was not initially substantial, it makes us forget to classify him metaphorically as the guy in mom’s basement with delusions of grandeur because his views were reality. Eastwood frames Jewell as the man that balances the scales in his relationship with his attorney and on the job as the man who actually does the work that other people get paid to do. They are like a real-life Laurel and Hardy.

Richard Jewell is also a movie about identity, and dreams contrasted with reality. Watson, Jewell, the FBI agent and the reporter are at points in their lives when they thought that they would have reached a certain echelon in their career, but instead they are all stuck in the same place—standing in the far corners of the shadows of those in the spotlight. Only Jewell is the real deal and makes his dream of protecting people come true. Jewell becomes a Rorschach test depending on others’ reaction to his success. Eastwood revels in visually comparing and contrasting the ones that look the part versus Jewell, who actually plays the part. Jewell looks like an overgrown schoolboy toddling around awkwardly with a cap and bookbag whereas Hamm, who plays the traditional, square jawed FBI agent. The rest of the movie is basically about sour grapes trying to retroactively make the story into something that they can understand, rationalizing that it is not that they did not measure up, but Jewell was the culprit and centralize their rightful role in the story by removing him from the pedestal so they can make their professional dreams come true. They are a bunch of mean bullies picking on the unpopular kid for having a good day. Only God can look in a man’s heart, but Eastwood’s explanation is convincing because it is universal to feel aggrieved regardless of which side of the divide that you fall on. Regardless of merit, dreams do not last long when exposed to the light of day.

Richard Jewell also furthers Eastwood’s political agenda by using a true story in hopes that viewers will extrapolate the lessons from Jewell’s plight and apply broadly in contexts where application of those lessons could be dangerous and foolish. Eastwood wants us to conclude that the enemy is the media and the government or at least people who work for the government. I am always fascinated that the people who express distrust of the government would, in the same breath, demand that others respect authority if they could not relate to them for some elusive reason (racism). It is unpatriotic and un-American when certain people do it then extremely patriotic and a fight against tyranny when others do the same thing. The real prejudice is against ordinary folk like Jewell whom the intelligentsia, government and media ridicule. In Jewell’s case, I agree because he was not guilty, but is Eastwood sharing, promoting and fomenting Presidon’t’s cries to liberate only if the government is not Republican or male?

Richard Jewell is actually one of Eastwood’s better latter films, but its reception by audiences was hurt when his onscreen depiction of a real life reporter, Kathy Scruggs, played memorably by Olivia Wilde, as a sexualized villain met against real world resistance from her fellow colleagues, including Ron Martz, who was portrayed as a character in the film, but not consulted in real life and was one of many who took umbrage to her cinematic treatment. Eastwood gives Scruggs the traditional woman villain treatment: vulgar, sexual, adopting traits that in a male are rewarded but are abhorrent in a woman. She happily accepts insults that she has balls, is ambitious, flaunts her beauty and says a story does not make her “hard.” She gets dressed down harder than any of the male characters who are villains and ends in a pool of tears. Most movies enjoy taking a high-powered woman and knocking her down a peg so Scruggs is no exception, but the catch is that Scruggs is dead in real life so Eastwood gave her the Jewell treatment while instructing audiences not to do the same thing. I guess that it is easier to look past the veneer for Eastwood if you are not a brassy dame who does not stick to gender norms. He would not budge on this issue even with numerous men defending Scruggs.

Richard Jewell’s most memorable woman character is Nadya Light, Watson’s secretary, Russian immigrant and later wife. She can be a brassy dame because she exists to assist Watson. She gets the best lines, is the comedic relief and steals every scene, which is hard to do if you are sharing a screen with famous scene chewer Sam Rockwell, who for once, does not play a lovable racist. Light starts the ball rolling with credible historical distrust of government, “Where I come from, when the government says someone’s guilty, its how you know they’re different. It’s different here.” She can say things like that because she has an Eastern European accent, and in American culture, people of a certain age associate immigrants with that accent as fleeing from communism so saying that you distrust a communist government is less inflammatory and is the gateway drug to distrusting our government. I am not going to pretend that I recognized Nina Arianda, who plays Light, but once I discovered it was her, I was not be surprised because she was the best part of Stan & Ollie and made the most of a tiny role in Florence Foster Jenkins. I need Arianda to be in everything yesterday. She is fabulous.

While Rockwell did a solid job, I found myself wondering if Billy Bob Thornton would have been better because Rockwell’s signature bombastic style works for the role, but is not necessarily faithful to the real life person, who seems less flashy. Is Paul Walter Hauser, who plays the titular role, a thespian? It is easy to forget that he is playing a character. I subconsciously associated him with the braggadocious culprit in I, Tonya before I looked up Hauser’s credits and realized that he is the same actor. It is easier to understand how people misjudged Jewel considering the Venn diagram shared by these two real life men, who were incredibly different.

On a technical note, I want to praise Eastwood’s judicious use of archival footage. He uses the real-life footage of an interview between Katie Couric and the real life Jewell, but keeps it far enough away not to create dissonance with the actor and uses Hauser’s voice. So many filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino make the mistake of mixing and matching which undercuts the movie. If I had to criticize Eastwood’s narrative structure, he either should have inflated the role that Jewell’s friends and colleagues played in his life, Dave Dutchess and Bill Miller, or omitted it completely because they were not so memorable to recognize them in subsequent scenes when they were simply in the background or referenced. I also hate it when films alternate between dates and a vague amount of time such as eight months later. Just give the damn date.

Richard Jewell was an interesting movie for me because I am a sports atheist and was in college just trying to survive at the time of the bombing so I went into the film not knowing much about the incident. It was new to me. I was struck by the fact that the woman who died in the bombing and Jewell were the same age when they died years apart, forty-four, and so many of the people featured in this movie are dead: Kenny Rogers, Scruggs, Muhammad Ali. I guess that it really was time to make a movie about this incident even though it feels as if it happened yesterday. Afterwards I felt satisfied reading a few Wikipedia entries and doing a few Google searches, but if you want to learn more about the real story behind Eastwood’s movie, the film is an adaptation of Marie Brenner’s Vanity Fair article, “American Nightmare: The Ballad of Richard Jewell” and Kent Alexander and Kevin Salwen’s book, The Suspect: An Olympic Bombing, the FBI, the Media and Richard Jewell, the Man Caught in the Middle. Fun fact: Brenner wrote another article that inspired The Insider.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.