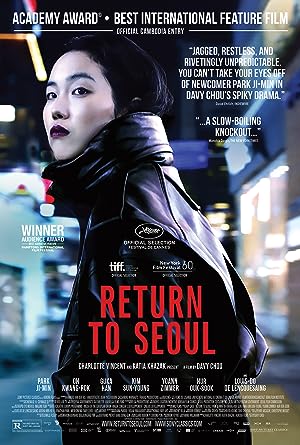

“Return to Seoul” (2022) is about Frederique “Freddie” Benoit (Park Ji-Min), who was born in South Korea, but put up for adoption until French parents adopted her. The film starts in 2014 with Freddie’s first visit to her birth nation at twenty-five years old, jumps forward to 2016 Tokyo, returns to South Korea complete with surgical and KN95 masks in 2021 then the Romanian countryside in 2022. It is an emotional coming of age journey where Freddie belongs everywhere and nowhere, but wherever you go, there you are.

“Return to Seoul” was a perfect, universally relatable movie with its specific, personal, fictional narrative. Laure Badulfle’s life loosely inspired Davy Chou, the Cambodian French writer, director and her friend. It is amazing how watching an actor convey an array of emotions can help a viewer reflect on their own unfamiliar emotional experience regardless of how different the circumstances are.

The first person that Chou shows is Tena (Guka Han), who is listening to South Korean music with her headphones on until she senses someone watching her. It is Freddie whose face is filled with delight in her sudden, fly by the seat of her pants immersion in a place that she had imagined. Tena, the plainclothes guest house concierge, along with a friend, takes Freddie out to eat, and Freddie is open until the friend admonishes her to obey a custom which is alien to her experience, which Freddie rejects with a smile on her face. She will fill her own glass with soju because no one cared for her otherwise she would not be visiting South Korea, and if it insults the other person, so be it. She will not pretend that she is ok, but she will self-medicate with less intimate conversation about her itinerary (is she going to look for her biological parents), alcohol and hook ups while strangers spit out words with French association while also claiming her as having an ancient Korean face.

Freddie goes from having no itinerary to being completely focused on finding her biological parents, but she is resentful of the process. There is some tension regarding whether she will find them, and even if she does, will they reciprocate the feeling. Even when her father (Oh Kwang-rok) and his family are repentant and embrace her, it is not a happy ending. The source of her identity crisis predates her existence with a change in the environment that created a chasm between her father’s family and the ocean/their livelihood. Tena acts as her initial interpreter, and her father’s family’s love is suffocating and demanding as if they are asking her to pretend there was no separation and resume life as a normal South Korean woman, which would erase her French/Western identity. She refuses to disguise her discomfort or reassure people when there is no way to reassure herself.

Even as she is clear about drawing boundaries, it is easy to see the family resemblance as she loses herself in alcohol and celebrates as if everything is fine when she returns to partying with young South Koreans. Afraid of intimacy in friendship and romantic relationships, she defaults to connecting through physical intercourse. Also rejection of authentic concern and love is a way to protect herself, play out the rejection that she felt in the beginning of her life without feeling the emotions that it provoked and having some control over the painful past in the present and create a familiar dynamic in an unfamiliar place. In each sequence, as she loses genuine people, it is painful to witness her throw away evolution instead of healing though understandable and human. She is demanding that this experience will be hers, not someone else even if well-meaning like her adoptive mother, who wanted to accompany her, Tena, who wants her to not throw away the Korean part of her life, or her family, who want her to know that they did not reject her.

When “Return to Seoul” jumped to the second time period, my armchair psychology radar started beeping, and I wondered if we were watching a normal reaction considering the circumstances, alcoholism and/or borderline personality disorder-change in appearance, profession and location, impulsive behavior, constant reinvention. Please call me out if I am incorrectly pathologizing normal behavior, but it seemed like a lot for one night. I thought it was a provocative choice for a Korean French person to feel more at home in Tokyo, especially considering Japan’s imperialistic rule over Korea. It is a strange compromise between France, another colonizing superpower, her Western side, but one that she cannot disappear in, and South Korea, which is as alien as it should be familiar yet also an inseparable part of her. When Andre, a French middle-aged hookup, calls her a Trojan Horse as an international consultant in Asia (I read it as a backhanded compliment like Oreo) and says, “You have to be able to not look back,” Freddie embraces the tough girl, cosmopolitan, world traveler image, but Park shows a flash of being wounded and unseen, alone even with company. She cannot help but look back, and even told Andre that, but her birth and adopted nation have hijacked her identity again. I also thought that it was interesting that her coworker friend was like Tena except not as wise at recognizing unhealthy coping mechanisms in their relationship dynamic. She is a perfect foil for Freddie as she discusses what a normal reunion with birth parents looks like. I also wondered how similar she was to her mother, a woman who preferred city life. The only moment of authentic connection is the next morning on a distant rooftop. It is the closest that we see to Freddie having a routine and seeming as if she has a home and can be at ease.

The third period is heartbreaking because we see Freddie in her dry drunk phase. It seems like she has finally gotten her act together, and even found a person whom she could connect with and act as a bridge with the past, but she understands that if birth connections can evaporate, even the most meaningful connection is temporal. All the stories that she tried to tell herself slip off as if they were ill-fitting clothes. When she gets her happy ending, Chou shoots it as if it is not solid, but keeps Freddie in the foreground as she experiences catharsis. Happy endings are also temporal.

The final act of “Return to Seoul” was bittersweet, but optimistic. It is everything that the earlier periods are not: foreign and solitary. The fact that Freddie can finally be alone with her thoughts and not divert herself was a beginning instead of an ending. We have no idea if we are seeing her or another phase, but the fact that she could create in that moment was energizing. It is a great bookend beginning and ending. She goes from talking about music to playing it. It is easy to forget that talking about something should not be equated with doing it.

Even though independent films usually do not have sequels, I want to revisit Freddie forever.