“Piety” (2022), “La Pietà” or “La Piedad” is a highly stylized film about a mother, Libertad (Ángela Molina), and her adult son, the pink-cheeked Mateo (Manel Llunell), who are unable to function without each other in 2011 Spain. When introduced, Mateo is content to spend every waking moment with his mother, which includes having dinner, watching news on the sofa, and cheering her in dance class while she sports a hanbok, a Korean traditional dress. North Korea dominates the television broadcast. Their reverie gets disturbed when Libertad confronts Mateo for ripping up a photograph of his estranged father, Roberto (Antonio Durán Morris). With illness and death threatening to separate them, Mateo finally decides to distance himself from his mother. Libertad reacts in extreme ways to keep him close. Will Mateo ever escape, and if he does, will he enjoy his freedom?

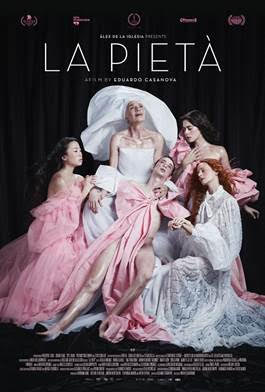

Writer and director Eduardo Casanova gives the “Phantom Thread” (2018) treatment to the love between a mother and son. Their world is a cross between a pink quilted Chanel bag and Gothic black, which represents the chasm, nothingness, death that Mateo experiences whenever he tries to separate from his mother. It takes twenty-one minutes before the title flashes onscreen, and Casanova recreates Michelangelo’s La Pietà, a sculpture of Mary mourning Jesus. Mateo faces an unspoken quandary: curiosity about his father, a feeling of betrayal because Roberto left when he was only a child having to satisfy his insatiably needy mother. Even though Libertad or Lili possesses such a domineering presence, Mateo is the real main character. During “Piety,” he goes through three stages: childhood, a rebellious adolescence and adulthood, which is signified in his reaction to his mother’s somewhat milder and campier impression of Kathy Bates in “Misery” (1990).

Molina is a legend in Spain, including some of Pedro Almodóvar’s best films, “Live Flesh” (1997) and “Broken Embraces” (2009), and recently appeared in “The Return” (2024) as the bellicose nurse and loyal attendant. She commits to a bonkers, monstrous character and remains sympathetic by mining the humor of the situation without being above it. Libertad conflates Mateo with herself while simultaneously terrified of the knowledge that they are two separate people. She even shocks herself at the lengths that she will take so they can stay together. Casanova parallels her to Kim Jong-Il, but the fascist world is vibrant though dangerous whereas the free world is drab and gray, a counter cultural parallel choice that defies the aesthetic of the classic 1984 Apple Macintosh Commercial but does feel like a homage to “Parasite” (2019).

The explicit parallels to the woes of a North Korean family hammers home Casanova’s point that abuse does not necessarily precede hatred, but adoration. It is the secular equivalent of the Biblical Hebrews escaping Egyptian enslavement then regretting the move. Arguably it is a heavy-handed way to make a point that should be clear in the leading Spanish portion of “Piety.” It also may be a controversial one. While the point of fiction, especially in such a surreal film, is to explore fantastical concepts without worrying about people confusing it with reality, North Korea is a real place, and the mourning of their leader/dictator happened. As Western outsiders, there is no way to know if that grief was a performance or authentic, which is how Casanova treats it. It is true that when North Koreans escape, their life can be harder—a reality that was the backstory of one of the characters in the first season of “Squid Game.” It would be interesting to know how Korean movie reviewers feel about the depiction of Koreans and North Korea even if it was intended to serve a metaphorical function.

As the denouement approaches, Libertad faces the natural consequences of her Munchausen syndrome by proxy and her need for control, power over others, not just her son. She confronts herself in an oneiric sequence and when she meets her ex-husband’s wife, Marta (Ana Polvorosa), who is Single White Female-ing her, it is the only time that she exists as an individual and not as a rabid guard dog for Mateo. She has the capacity to interact with others and see them. The end becomes an exploration of different reasons for women engaging in motherhood, and Libertad, whose name means freedom, starts to literally imitate and mirror Mateo as he used to do with her. Her change of heart and emerging selflessness feels like the least realistic aspect of “Piety,” but Mateo’s reaction to her decision is the rawest, most grounded emotional moment and creates the perfect ending. Somewhere Lars von Trier is jealous, and Casanova bests Almodóvar’s latest film, “The Room Next Door” (2024), in the way that it treats illness and mortality even if it is in an exaggerated way.

“Piety” is not a horror movie, but it has horror movie elements. While the air is fraught with Oedipal complexities, there is no incest in the strict definition of the term. The full-frontal nudity is not sensual or erotic, but clinical, incidental and blunt. Casanova comes pretty close though, but for all the distorted, graphic moments, I only had to look away over the pinky toe. Somewhere the “Game of Thrones” creators are puking. While Mateo and Libertad take turns being Jesus figures, and the theme of mother and son immortalized in art over the unnatural, brutal torture and subsequent death of a son before his mother in an orgy of immortalized grief is impossible to miss. It also feels vaguely blasphemous and reverent.

“Piety” is blasphemous for the contemporary take on the iconographic imagery, but reverent in the way that Casanova expresses an appreciation for the flawed ways that mothers exist in relation to their children, even when it is toxic to both, and obliterate their individual identities. It is an irreplaceable relationship, which underscores how important it is for parents to prepare their children to exist independently so they can save them long after they are gone.

On another level, though it may not be intentional, “Piety” could be seen as a political movie. Casanova conveys the allure of authoritarianism and its anti-life, abnormal repulsiveness. It is a Jonestown death cult for a party of two or a nation. With the global threat of fascism rearing its head once more, it is less controversial to make a movie about a demented mother and son relationship than an explicit critique of nation states turning on its people and demanding that they love their own obliteration. Allegedly free nations do not get off the hook easily in its callous indifference to emotion and individuality.

“Piety” is an extreme movie that will have some clutching their pearls and foaming at the mouth with outrage, and others will declare it to be the second coming of Peter Greenaway without a mean streak. Casanova swings big, and while his audaciousness does not always stick the landing, his commitment to his bizarre vision may make him one of the greats. Unlike Jacques Audiard, Casanova’s work is consistent, confident and daring without collapsing under the weight of undisciplined excess.