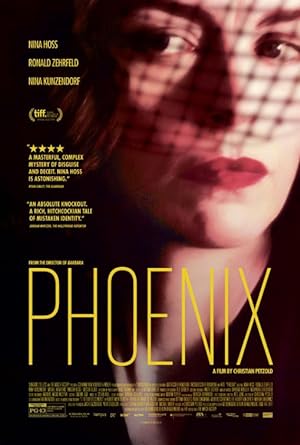

Phoenix is a German movie about a woman returning from Auschwitz to Berlin trying to recover from physical wounds inflicted during the Holocaust and psychological wounds which may have originated before the Nazis seized her. She suffers from an identity crisis since her reason for living may no longer exist. The movie’s central question is who are you after everything that you were externally is gone.

When I saw previews for Phoenix, I knew that I would not see it in theaters because I generally despise fictional films about the Holocaust, but I would have changed my mind if I had realized that it was made by the same director and actors that made Barbara. Because Nina Hoss is one of the best actors alive, I put Phoenix in my queue and was not disappointed. I would caution viewers to watch it when you have three hours and sixteen minutes to spare because I watched it two times: the first time to understand what was going on and the second time to make sure that I did not overlook any narrative detail.

Phoenix feels like a sci fi historical film. The first half hour involves facial reconstruction or recreation surgery that may or may not be based in reality and depicts her physical recovery. The main character, Nelly, suffers what should have been a mortal injury, but survives. It is medically impossible for her to look like herself, but she still ends up a beautiful woman albeit an initially shattered one. Once she is physically restored, the remaining hour depicts her psychological recovery as she begins to reclaim her external identity markers that make her recognizable to the people who knew her, her German friends and husband. In a shocking twist, it is her husband who unwittingly helps her to recreate herself in an effort to get money. We get to understand what Kim Novak felt in Vertigo, but with tremendously higher stakes.

The first time that I watched Phoenix, I was extremely angry with Nelly.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Nelly knew who were her real people and who were not, and instead of choosing Lene and looking forward, she runs towards the people who betrayed her and tries to rationalize the circumstances of her destruction. While she may be technically correct that she is not Jewish because she is not observant, her denial of her heritage coupled with her behavior is reminiscent of people who hate themselves and would prefer to identify with their persecutors than others who are actually like them even if they are better than them. Is there a word that Jewish people use amongst themselves like black people use coon to describe other black people who behave similar to Nelly? She abases herself to find her husband by running after every guy named Johnny even if Johnny could be the kind of guy that drags women into a dark alley and abuses them. She is so obedient to men. She stops when they tell her to stop. She barely notices when they touch her. She is only focused on one thing: finding her husband. When she does find him, she allows him to act like Pygmalion instead of being horrified that he seems more concerned about money than his wife. Considering that Nelly seems more troubled with the people who did not care for her than the ones who did, this behavior is not shocking. Betrayal may be a characteristic shared by the couple.

My initial impression of Nelly is not a complete profile. Perhaps her obedience is a side effect of trauma when life and death may be dependent on how quickly and unquestioningly you obeyed someone in the death camps. She cannot be expected to act differently so soon, but she is not as malleable as she appears. Nelly does rebel when she wants to. She transforms from a shrinking, trembling woman hugging the furthest corners of cars to a fearless figure shakily searching for her husband through the ruined streets of Berlin. Despite fear and physical weakness, she is like the lover in Song of Solomon 3:2, “I will get up now and go about the city, through its streets and squares; I will search for the one my heart loves. So I looked for him, but did not find him.” The only glimpse of Nelly during the war is in a dream, dressed in stripes, covered in shadows, watching her husband near her old hiding space at the beach house. Nelly’s motivation for living was her husband.

Nelly’s stubbornness and focus is a rejection of the fiction that Nazis tried to impose upon her life. She chooses to reclaim the life that she had before the war, not believe the Nazis’ claim that she has no right to Germany, Berlin, her career/her voice, her husband and friends. She resists others when they try to distract her from her goal: when Lene tries to get her to move to Palestine, when Johnny tries to get her to leave his flat, when Johnny chastises her for not being good enough. More importantly, she rejects attempts to erase her more recent past, the reality of her trauma. The only time that she considers harming Johnny is when he is about to see her arm. She does not want him to see her tattoo, but she is also disgusted at the idea of removing it. The lack of interest in her story after the Nazis take her is the real betrayal. She gradually begins to recognize that they never saw her even before she was shot in the face.

There is the fantasy versus the reality of reunion. Nelly visibly flinches when her husband accurately states that people shrink away from survivors, and no one will ask her what happened in the camps. Even Lene never asks, but considering that she volunteered and worked on nothing but what happened in the camps, Lene’s reticence is tact, not selfishness or rejection of guilt in the complicit destruction of fellow Germans. People untouched by trauma want people to emerge from trauma as if they never experienced it and act as silent receptacles for their tales of loss and memories. They don’t actually care about the survivor, but how the survivor makes them feel. They actually don’t care about the survivor. Nelly wants to be old Nelly, but she also wants people to recognize her. When she introduces herself to her husband, she chooses the name of a friend who did not survive, Esther. She wants to be old Nelly, but she also has no desire to erase what happened after old Nelly died. She may reject being Jewish, but she claims a more Jewish identity to represent the person that she became in Auschwitz.

The last hour of Phoenix is reminiscent of Memento without the hyperstylized editing. By the end of the film, we finally know who Nelly is, which is one reason why I wanted to watch the film again. Now that I finally understood what she wanted and how she saw herself, I could rewatch the film with a more perceptive eye. She is not some weak woman who cannot live without her man. She merges her traumatized self with her past self instead of living a fractured life where she refers to her past self in the third person. It is only after she reclaims her identity and her life that she is able to confront the quality of that life and decide whether or not to move forward.

Without an emotionally violent response, she simply stares in disbelief as her friends, some of whom shunned her during the war, warmly greet her. She receives them stiffly then silences them by singing “Speak Low,” which is heard at various times throughout the film. It is their turn to stare in shock at her, and she simply leaves. She gets her dream to come true: to sing in Berlin with Johnny. The song choice indicates that she knows that the dream is over. The end is haunting because we don’t know what Nelly will do next. She literally has no one, including Lene, who gives in to despair. Nelly and Lene arrive at the same conclusion. They leave these trash, inadequate people who do not deserve them, not even their anger.

It is a testament to Ronald Zehrfeld’s talents that he is able to play Johnny without making us want to punch him. Hoss and Zehrfeld worked together in Barbara as a slightly more hopeful pair. They seem to be the iconic fictional historical yet human faces of Germany in times of trauma, which is a lot of weight to put on actors’ shoulders, but they never break under the weight. Many of the scenes in wooded areas or on bikes reminded me of Barbara. Is the director, Christian Pezold, going backwards in time with his films? Will post WWI be next? Pezold deserves high praise for tackling a horrific historical subject in a fictional context without cheapening the past, alleviating the burden and authentically communicating emotions.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.