This review was originally published on Roarfeminist.org

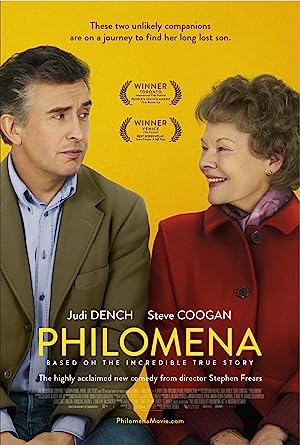

Philomena is an adaptation of a book based on a true story about Martin Sixsmith, an unemployed government adviser, played by Steve Coogan. While trying to find his bearings, a waitress approaches him to ask for help investigating her mother’s story. He isn’t interested until he is and ends up irrevocably emotionally invested with the mother, who is the titular character and played by Judi Dench. They try to find her son, who was stolen from her or given up for adoption depending on your perspective.

When I first saw Philomena, I unfavorably compared it to The Magdalene Sisters. I was frustrated that a lot of my questions did not get answered or certain details were not highlighted more, but explained with an almost indiscernible moment such as Coogan on a phone call, and the viewer could only hear his end of the call then like magic, information is suddenly available. How did she get out of that place? Why was the husband so against seeing her? I understand that it was probably a dramatic choice that gives her a moment to take control instead of being passive, but it is still inexplicable.

There is literally no story without Martin, but during the initial viewing, I was annoyed that he was the central character. If he is going to be the focus of the plot, then we needed more details about his life. His disgrace needed to be more spelled out then simply alluded to or referenced as if we already know what happened. There is a moment at a cocktail party when he corrects someone about a public misunderstanding, and I suppose that we are supposed to just assume that this story explains why the administration let him go, but when it comes to government, I assume nothing. His wife is cool with him just disappearing for a long stretch of time and spending all the money? We see her for a few minutes at the beginning of the film then she just disappears. We see his editor, Lady Stark (!), more often. If the story was not based on real life, I would think that there is a British odd couple trope of a middle aged, fussy, intellectual man paired with an older woman from a less privileged socioeconomic class, which I saw previously in The Lady in the Van and is also based on real people.

If I didn’t like Philomena, then why was I compelled to watch it a second time? Sure, I wanted my questions answered, and some of them were. I was still frustrated that a lot of information is given in blink and miss it moments. I think that fifty-three minutes into the initial viewing, I realized that I was not judging the movie on its own merits because it suddenly felt absorbing and amazing. Philomena is actually a sophisticated piece of work that manages to feel light and funny as it interweaves overarching themes that span decades and privileges an emotional portrait that requires two characters, not one, to show the spectrum of appropriate responses to these conflicts. I still think that my early criticism of omitting or speeding through certain details stands, but the movie is like volleyball. If you take the time to explain the moves, the ball drops. Spoilers to follow.

Philomena is about dealing with one’s powerlessness and trauma from dealing with casual institutional exploitation and cruelty from the government and the Catholic Church. These stories keep happening. Because both Philomena and Martin are dealing with something that personally happened to them, but also able to focus on something that happened to someone else, her son, which suddenly gives them permission to be emotional instead of just resilient or unquestionably accepting the situation. To advocate on behalf of someone is to learn how to advocate on your own behalf. Martin definitely has some church trauma because at the beginning of the film, he walks out of a Christmas service, the most innocuous of services, but we never find out the source of his anger. Regarding the loss of his job, he tries to be accepting and understands that it is the nature of the business to have a scapegoat whereas Philomena admonishes him that his friends are not his friends. His new running routine is akin to her confessional. Philomena goes to church even though the church almost killed her, did not give her adequate health care, enslaved her, sold her baby for profit then kept them apart. He challenges her loyalty, and for the first time, she decides that she cannot bear to be in church and leaves abruptly. The interplay continues in the son’s story: he works for three Republican administrations and dies of AIDS.

Why do people feel compelled to show loyalty and allegiance to institutions that hate and destroy them? How do you distinguish between institutions and the ideals that the institutions uphold? While Philomena’s way of coping is more acceptable and “Christian,” Martin’s sense of outrage is also acceptable. Jesus flipped tables in a temple. I appreciated the idea that the only thing that changes about institutions is the surface. Early in the movie, there is this idea that the Catholic Church is not as stark and brutal as it was when Philomena was first imprisoned at the orphanage. They offer her tea. They are solicitous. By the end of the film, we know that nothing substantial has changed. The new church is the old church with better PR people. The individual response to institutional abuse is ultimately irrelevant if the institution is unchanging.

There are a lot of class issues that are used for comedy relief. Philomena is astonished by all the comforts that Martin takes for granted whereas Martin is slightly unmoored in economy class. His disdain for human interest and certain forms of entertainment are characterized as an emotional arrested development whereas Philomena’s openness and joy in cheesy entertainment is viewed as adorable. While Martin is abrupt in his relationships, he later recognizes it and learns to be patient and empathetic. I think that the film’s criticism and growth of Martin’s character is fair, but the film missed an opportunity to help Philomena grow.

Maybe because she is seen as the victim or people like to excuse old people like they do children, Philomena overlooks this potential for character growth, but children get instruction when they make a misstep. Stop coddling older people and dismissing it as charming or adorable! Her relative sophistication regarding sex and sexual orientation suggests that she is capable of more and only needed a gentle nudge in the right direction. She was casually, unintentionally racist. She tries to engage the Mexican omelet chef in a discussion about nachos, and he politely and cheeringly ushers her off with more food, but I am sure that if the camera lingered longer on him, he would have rolled his eyes. “The little black man pretending to be a big fat lady” line insured that I was not going to pay to see it in the theaters.

Philomena may be a flawed movie, but it intrigued me so much that I will read The Lost Child of Philomena Lee.