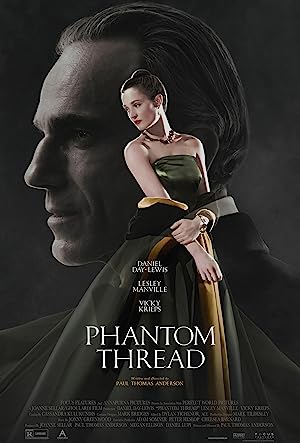

Even though I had no idea what was going on while I was watching it, Phantom Thread didn’t make me mad so it is definitely art. If you think of it as a film from a distorted perspective, it could help. The visually sumptuous movie focuses on three characters: Reynolds Woodcock played by Daniel Day-Lewis, Cyril, his sister, played by Lesley Manville, who seems related to Catherine Frot, and his muse, Alma, played by Vicky Krieps. The acting is seamless. The events seem based in reality until it couldn’t possibly be. Even though Woodcock seems to be the dominant force in this weird relationship, Alma is the narrator who frames and ultimately guides the direction of the story. Initially she seems like a willing blank slate to Woodcock’s whims and Cyril’s instructions, but Galatea is not as pliable as she appears and makes her presence felt in small and large ways until she becomes an essential part of their lives.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

There are two crucial moments that define the movie. The first is when Woodcock says, “It’s comforting to think the dead are watching over the living. I don’t find that spooky at all.” Phantom Thread could be a synonym for a ghost story, but should not be seen as a horror film. If the dead are comforting, then the ability to feel their presence is a type of communion of the saints, living and dead. Alma wields this power. The second is that what we are seeing is Alma telling a story to the doctor while Woodcock is ill and resting on her lap, consenting and alive, but not dominant. Paul Thomas Anderson’s movie is primarily her story although she is more inscrutable than Woodcock. They are different sides of the same coin, people with a warped view of life, love and death, but are happy in their dysfunctional kick.

On a more human practical level, as Woodcock dominated her on their first date and immediately introduced his sister, I kept hearing, “It puts the lotion in the basket.” Any woman who does not run after that first date has worst alternatives or is not too sound in mind and spirit. Alma is an immigrant of some sort. She goes from working class to skilled apprentice in one of the grandest fashion houses in Europe. We know nothing about her past. She seems to be connected to no one and has no life of her own so is able to seemingly give herself completely, but is not deferential if she does not like the way that things are playing out.

She makes her presence known with insignificant details that seem outlandishly boorish to Woodcock: the way that she eats, pours tea, insists on cooking with butter, winning a staring contest. She provokes Woodcock into disobeying his sister by invoking his pride in his creation. When he is at the threshold of calling it quits, she feeds him poison. He likes it. She creates a space for herself not given to her by Woodcock or instructed by Cyril. Kids, if you are dating a jerk, you are not allowed to poison him even if he likes it. He thinks poison is nourishing. He cannot accept love without ceding his dominance. He can only accept people who can hurt him.

What is wrong with these people? Superficially Phantom Thread occurs in post World War II London. After Reynolds and Alma marry, a woman stirs the pot by erroneously suggesting that his wife is busy flirting and not looking at him during the dinner party. He lets the woman make unsavory comments about her immigrant status without taking offense or defending her because she is expressing the hostility that he feels for the way that Alma intrudes on his life, his work. He is disgusted by having to participate in a vulgar marriage ceremony between a wealthy woman and a South American man who sold visas to European Jews as if that was a bad thing given the alternative, although it does suggest that the husband is a war profiteer, not a humanitarian. Woodcock is bothered by the imbibing, the lack of elegance, not the scandal. He seems completely unconcerned with politics, but roots himself in the eternal: wealthy families, royalty. He could not possibly have served during WWII although how he escaped such duties is elusive. How did his mother die? More importantly, he seems untroubled by his father’s absence and untouched by his stepfather’s father except his design of his mother’s wedding dress. He seems untouched by war perhaps because he has willfully retreated into routine to keep away from horror so he has no normal way of processing danger or only processes opportunity within the negative-as a creative challenge. Making a wedding dress for your mother is like a weird form of time travel to insure that you will be born. His sister is far more practical about how things function.

If Woodcock is a man who thrived untouched by the bombing and destruction of WWII, then Alma may be the opposite. She is flexible and does not think that he is so bad because she has fled worse. She is willing to go along and is not bothered by being stripped down, instructed and examined because it is not a new sensation, and she has an innate sense of how far she can go without being erased. Her sense of what is right and wrong is so damaged that it is reminiscent of Roman Polanski’s moral relativism after emerging from the horrors of Nazi occupation. I am not saying that she was even directly harmed by it, but she left her past for some reason, and her initial delight in their sexless domination game was reminiscent of The Night Porter even if he did not know that he was playing. Alma has a past, but she does not speak of it.

Anderson sees himself in Woodcock, the visionary who must always be in control and have things just so. He said that his inspiration for Alma is Maya Rudolph, his wife, whom he saw a look of adoration in her face while she was caring for him when he was sick. I obviously don’t know these people personally. Only a person with a big ego could see behind the scenes Alma in such a consummate performer and big personality as Rudolph. Does he see her as a person without a past, whose main identity is defined by her relationship to him? Does he see himself as a man untouched by the scars of his nation, only dominated by his work, so post racial that he literally cannot imagine race in his work so his imagination can only thrive in the London of Christopher Nolan’s imagination. Even while hearing assaults on his wife’s character based on her origins, he feels no need to defend her, but only sees it as an external manifestation of his negativity and how much he wants her to stop affecting his work while simultaneously tiring of his work and knowing that if he surrendered to her, life would become better. Cyril is more of a mystery, but my favorite character after her little dressing down of Woodcock, “Don’t pick a fight with me, you certainly won’t come out alive. I’ll go right through you, and it’ll be you who ends up on the floor.”

Anderson seems to be on the verge of an epiphany about his relationship to work and the women in his life. Phantom Thread acknowledges that his view is demented and damaging, but he is unable to cast off the sickness and function normally because it is more important to be special than a fully functioning human being. Please get therapy or keep making films.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.