Thespian Rebecca Hall makes her directorial debut by adapting Nella Larsen’s novel by the same name, “Passing” (2021). Her choice made me silently squeal with delight because ever since I knew of Hall’s existence, I have identified her as a black mixed-race woman who may not identify as black since she was not born in the US. Filmmakers such as Woody Allen probably did not know about Hall’s heritage based on the characters that she played. The only way that I could have been more thrilled that she was coming out of the race closet was if she had played one of the two main characters in the film because she really can pass. I only knew about her heritage when I looked up her bio.

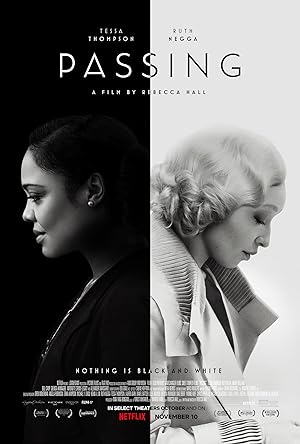

“Passing” stars Tessa Thompson as Irene or Rennie, a doctor’s wife and mother of two who temporarily passes as white while shopping. She bumps into a high school friend, Clare (Ruth Negga), who chose to do it full time and even married a prosperous racist white man (Alexander Skarsgard, Hall’s “Godzilla vs. Kong” costar). Irene ignores Clare’s overtures of friendship and disguises her reason as concern for Clare and her child’s safety but as they grow closer, Irene destabilizes and cannot quite face her own reasons for preferring that Clare sticks with her initial life choices instead of coming home.

“Passing” is a period movie set during Prohibition 1920s and the Harlem Renaissance. Hall chooses to make a black and white film, but unlike Todd Haynes’ “Far from Heaven” (2002) and “Carol” (2015), this film does not feel like a highly stylized, almost bloodless representation of an era. Instead black and white film is a visual metaphor for how Irene and Clare as foils are photograph negatives of the other woman. When Clare initially appears, it is as a blinding white light that shocks Irene like a sunrise, a glimpse of heaven. Irene’s world is visibly, literally darker-greys until the final scenes when it is night. Hall makes a deliberate, carefully crafted film. If her film is flawed, it is because Hall has too much faith in the viewer and leaves a lot to the imagination in determining whether Irene is an unreliable narrator. Viewers familiar with the original story will have an advantage of understanding the significance of her mise en scene and editorial choices better whereas those viewers who are not may be left puzzled until the end. Larson’s novel has an ambiguous ending, but Hall has a particular reading of the end and takes a firm stance on Irene’s actions.

Hall’s film explores every definition of passing. There is the common definition of people or objects passing each other, only briefly interacting and sharing a moment, which she depicts in the opening scenes. Passing can also be defined as time moving, which Hall also explores and begins the film in the summer with the blaring sun creating an overexposure effect, has an autumnal middle where the film begins to darken and children learn about death then ends with winter and the white of the snow like a bookend to summer. Passing can describe an action such as Irene’s children throwing around a ball or someone dying. Larsen was explicitly referring to the act of a black person whom white people could mistake for being white. The opening scenes feel more as if it is a spy movie with Irene hiding her face with a hat and constantly applying powder while keenly observing people to see if she is about to be spotted so she can make a quick getaway.

Hall implies another definition for passing: a person with a LGBTQ sexual orientation who acts as if they are heterosexual. Hall and Thompson portray Irene as someone sexually attracted to Claire. When Irene goes to The Drayton Hotel for refreshments, she sees a romantic couple and two silent elderly women. When Irene notices Clare, she looks at her legs first. During the fall sequence, she covers Clare’s legs. At a party, she lingers her gaze on Clare’s bare back and grabs her hand. When Irene says it is not safe for Clare to be there, it has a double meaning. It is not safe for her because she is attracted to Clare. After Irene’s initial encounter with Clare, she instigates a sexual encounter with her husband, Brian (Andre Holland), who is surprised. Later discussions reflect that Brian is dissatisfied with Irene’s prudishness. After her second meeting with Clare, while in bed with her husband, she cannot stop remarking on Clare’s beauty.

Irene exorcises her sexual attraction to Claire by acting on it with an acceptable person, Brian. When Clare and Brian first meet at their home, Hall depicts the scene in two ways. From Irene’s point of view in the mirror, their reflections seem inappropriately close, but as Irene looks at them and not the mirror, they are acting normal, which reflects that Irene is an unreliable narrator whose desires overpower and distort her view. She arranges for Brian and Clare to engage in activities without her as if she wants to vicariously enjoy Clare through Brian then later accuses Brian of being attracted to Clare. While suspicion can be warranted since Brian tries to hide when he talks to Clare without Irene before a tea party and other characters such as Irene’s friend, Hugh (Bill Camp), a white male novelist, notices Brian’s defensiveness of Clare, which is a huge change from his earlier ridicule before he met her, Brian notes that when Irene accuses him, he was not talking about Clare and has always been trying to leave the country, which is true. Irene’s main characteristic is to seem as if she is having a conversation with someone else, but she is only expressing what is dominating her thoughts—her own attraction and fear of jeopardizing her safety.

Even though Irene is the protagonist, Clare is a more interesting character because she is more open when she appears in “Passing,” which is counterintuitive considering that her character is living a lie. Clare’s presence is unintentionally disruptive. In addition to race, she disturbs class lines by being just as comfortable with Zu (Ashley Ware Jenkins), Irene’s maid, as anyone else and talking about her dad being a janitor whereas Irene wants more regimented divisions. Negga’s take on Claire transports us to the late 1920s as she utilizes her big eyes and transforms her voice and mannerisms to fit a dame from that era without going over the top. If placed in a room with Barbara Stanwyck, there would be no dissonance. Negga is historically the most riveting person on any screen from “Agents of S.H.I.E.LD.” to “Loving” (2016).

In contrast, Thompson’s character is more cryptic and has a harder job since Irene is probably a bit of a mystery to herself. Because Thompson is so well known as a bisexual cis woman known for playing powerful roles, a viewer such as myself bringing that knowledge to the movie cannot say whether she failed to convey other notes through her body language and emotions projected on her face though she did with her voice. Towards the end, Thompson becomes Joan Crawfordesque, but something about Thompson seems rigidly twenty-first century. While Irene is wedded first to her black community, which makes her find Clare somewhat revolting, and repulses her husband’s efforts to consider leaving her “home,” “Passing” depicts her as socializing more with Hugh and Felise (Antoinette Crowe-Legacy), an Amazonian black woman who plays a more physical, protective role in the denouement than any other character. Even though Irene identifies as a mother and wife and socializes in majority black groups, other than her family, she spends more one on one time being herself with white male characters or statuesque black women. She accepts gender normative roles, but seems to breathe easier outside of them. When Irene appears to be losing it, it is during the times when her husband and sons form a unit without her while she is exiled to the borders performing more traditional woman duties such as housekeeping. Claire is also not present at her times of heightened emotional disturbance though Irene blames her for the disruption. Breaking the teapot could have multiple meanings.

I had tremendous difficulty immersing myself in “Passing” because I could not stop asking myself if Thompson and Negga could pass as white. Is it because they are famous or because I am black that I could not suspend disbelief that they could be seen as white? Negga never seemed more black than as Clare, especially as the movie unfolded, and after she started getting closer to Zu. Thompson only seems black to me.

I wanted more Zu. She seemed frightened of Claire then was later friends with her. Zu is an intersectional figure because while she is a black woman working for a black woman, Irene relates to her more as a convenience than a person with a full life. Because we are seeing the film from Irene’s perspective, we don’t get to see Zu as a three-dimensional figure, but Jenkins does her best to inject as much into her onscreen moments as possible.

“Passing” is the kind of film that will benefit from repeat viewing. It is a gorgeous, thoughtful film that begins to lose momentum as it approaches the denouement, but when it ends, you will want to watch it again to catch all the moments that you may have missed. I look forward to Hall doing more work behind the camera.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

I have no idea if Hall intended to make “Passing” as a horror movie, but with repeat viewing, Irene reminded me of Norman Bates from “Bates Motel.” While Clare acknowledges that she is ruthless when it comes to her desires, Irene is as well, but just hides it under an affable mask. Irene tends to snap at anyone who threatens the stability of her home in a way that she is not entirely conscious. When Norman feels sexual attraction or is threatened, he takes on the persona of his mother, a person whom he views as strong, ruthless when it comes to defending her child and sexual in a way that is not open to him. Norman is not conscious of this shift, but Clare is more premeditated and disturbed by this aspect of her personality. Instead of becoming her own mother, she takes refuge in her role as a covert terrible mother.

In “Passing,” her first victim is Clare, but it could easily be anyone whom Irene perceives to threaten her children and her relationship with her children. She gets most agitated when Brian introduces the children to “the race problem,” i.e. lynching. Because she can’t single handedly murder all racists, she disagrees with her husband. She is also opposed to Brian’s desire to leave the country because like Norman, her identity seems to be tied to the house in a way that is not explicitly addressed in the film. Without Brian, she cannot maintain the house so she blames Clare, the source of her sexual frustration, but if not for Clare, Brian could have easily become her first victim.

When we meet Irene, she is already in disguise as a white woman and willing to transgress boundaries for her children, which then segues into indulging in lecherous glances at women. The cover story for transgressing is for her sons, but she is really fulfilling her own desires. She is not just vigilant and watching people to protect herself, but because she is surveilling people. While Clare watches Irene out of recognition, Irene’s gaze is more voyeuristic and later predatory. Before Clare appears, Irene is shifting her identity and experimenting with her children as the veneer. Her hysterical laughter upon hearing Clare’s racist husband’s joke is a touch too hysterical for an ordinary black woman trapped in an uncomfortable situation.

She enjoys opening windows, breaking things as opposed to small animals, dominating Zu and not seeing her as human, has considered the price for murder, capital punishment, which would take her away from her home and her children so is unacceptable. Long before Clare arrived, Irene had been contemplating these things, but Clare just amplified them. Hall may not have intended to imply that Irene was experimenting in a way that was not just a benign response to societal pressures, but “Passing” becomes a portrait of escalation from harmless transgressor to murderer, Irene’s journey to overcome societal barriers over to criminality. Because we do not have many portraits of women murderers, it is only in retrospect that a pattern emerges. While watching Irene, it is easy to rationalize moments as casual, accidental, or normal, but Clare is the antidote to those assumptions. Clare is normal in comparison because she pretends to get what she wants to make her life easier whereas Irene pretends to be normal-a black, heterosexual woman and mother. Clare is oblivious that she is blowing Irene’s cover. Irene is not normal and would do anything to get what she wants. Clare jokes about killing. Irene does it. How did she get that house? Did she inherit when a relative died? If there is a sequel, Irene finds a way to kill Brian. Unfortunately it plays into a psycho queer trope, but because the psycho part is so understated and unexpected, a real plot twist, I’m wondering if “Passing” is an exception.