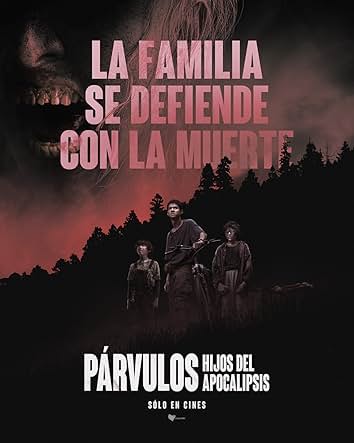

“Párvulos: Children of the Apocalypse” (2024) is a Mexican zombie film that could have been set in the same world as “I Am Legend” (2007), “Day of the Dead” (1985) and “The Walking Dead.” Three brothers, Salvador (Farid Esclalante Correa), nicknamed Chava or Caca when his brothers are angry with him, Oliver (Leonardo Cervantes), nicknamed Oli, and Benjamin (Mateo Ortega Casillas), nicknamed Benja, are surviving on their own in a cabin in the woods after a pandemic destroys the world. After Benjamin gets curious and disobeys orders, it changes everything for their family. This coming-of-age film proves that there is still life in zombie horror.

Horror films from South American countries are not for the faint hearted. Do not think that child actors will deter filmmakers from pushing boundaries and trampling taboos. The first onscreen death is killing a dog, and the dog is just an appetizer for the atrocities that lie ahead. The film implicitly asks what makes some worthy of love and others’ lives without value. Salvador is the oldest, a teenager frustrated with having to raise his brothers without privacy. Parentification is abuse, but it is a dystopia, so everything is toxic. Salvador protects his brothers from themselves, a band of men called the trumpets who kill other survivors, and the infected, who are technically not zombies because they are alive. Oli is the bookends narrator who sets the stage for the audience. There are only two consistent states: family and change. Oli is easy to forget. He mostly obeys Salvador but is closer to age and sentiment as Benji. Benji winds up being the de facto head of the family, but is still a child, which sets the family up for disaster. His sense of morality is tied to his heart: killing dogs is fine, but frogs are off limits. Because he is a kid, his older brothers indulge him, but spoiling a kid during a zombie apocalypse is only a good idea if you believe that people are inherently good. Spoiler alert: they are not.

Cowriter Ricardo Aguado-Fentanes and cowriter/director Isaac Ezban succeed at finding ways to reanimate the zombie horror movie. Just when a moviegoer believes that they know which direction the story is going, the filmmakers switch things up. The world gets adorable and heartwarming as the boys celebrate Christmas under gruesome conditions. When Valeria (Carla Adell), a young woman, appears, it feels like the family will be complete, and Salvador won the jackpot, but then the tone shifts again and becomes a moral quandary. When children are taught that only family matters, it has the unfortunate consequence of dehumanizing other people. While Salvador recognizes her as human because he was brought up in the normal world, his brothers do not. It is a chilling concept that these children are the only hope for the future of humanity. Their lack of a moral compass holds the seeds of their destruction and salvation. In a world that will show no mercy to children, maybe there is a slight advantage if the children are not burdened with ethics.

Even though the overall tone and scenario seems cheerier, funnier and less demented, “Párvulos: Children of the Apocalypse” may be bleaker than Yorgos Lanthimos’ “Dogtooth” (2009). There is a burden of family systems distorting natural instincts. This movie and “The Hole in the Fence” (2022), both Mexican films, frame the film as if it segues from the natural world to man as a part of that world, but man’s world is not natural. It is constructed. While they may live in an isolated place, the children are actually living in an overgrown resort area. Their lives are not natural, and neither are the burdens that they choose to carry. It is a complete perversion of life even if family love motivates them, and they are often relatable. It is not groundbreaking for zombie films to depict the human beings as the real monsters, but it is still shocking to see children in that light. There are no good guys in this film.

Cinematographer Rodrigo Sandoval creates a world that almost seems black and white so the flashes of color, particularly red, is more shocking when it erupts. Think “Sin City” (2005). Ezban is deft at establishing routine whether it is playing the one record, Helado Salvaje’s “Bizarro Sound” or watching the same movie, “The Congress” (2013), which is an animated film for adults. “Hansel and Gretel” is a fairy tale told throughout “Párvulos: Children of the Apocalypse.” It resonates with the children because of the idea of parents abandoning them in the woods, hunger and cannibalism. When the story’s trajectory shifts, Ezban shows it and masters montages conveying the emotional tone. He also threads enough mystery through the story to keep his audience invested: what are the noises in the basement, can Benja’s outlandish ideas work and why are the trumpets homicidal maniacs?

“Párvulos: Children of the Apocalypse” is set at Christmas time, but the kids are celebrating it as a secular holiday with no sense of religion. The trumpets are religious fanatics who stole some lines out of the Book of Revelation, the 144,000 righteous, to rationalize their new synthetic god, which is a neat plot twist and makes sense that their new deity would relate to their current circumstances. They also rationalize cruelty to children with the story of Abraham sacrificing Isaac. It is not the only religious allusion. The resort is called Jacob’s Cabin, and the slogan on the billboard translates to “fun for the whole family.” Ha! “Párvulos” translates to little ones, which also has a Biblical connotation based in Matthew 18: 6, “If anyone causes one of these little ones—those who believe in me—to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea.” Benjamin was the youngest brother in Joseph’s family whom everyone loved, which is saying something since most of the brothers wanted to kill Joseph. All these allusions are turned upside down. Jacob was not a hunter, but this cabin is full of death.

Even if you got tired of zombie horror, “Párvulos: Children of the Apocalypse” is worth returning to the genre.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Like Bub from “Day of the Dead,” zombies can be trained and are cared for like animals with chain leashes, kitty litter for their waste, taken for walks, wear muzzles and washed outdoors. They even have sex. The zombie virus expands into a metaphor of children sacrificing their lives and mental health to be family caretakers without the maturity and judgment to do so effectively. It is monstrous for children to take care of adults. During Christmas dinner, the zombies act like children spitting out food and playing with spoons. Considering that the last two years have seen a resurgence of hagsploitation with “The Front Room” (2024) and “The Rule of Jenny Pen” (2024), using zombies is a subversive and fresh way to examine the strain of age and declining health. It is not a surprise that the filmmakers return to the usual zombie storylines because the middle section is the most avant garde part.