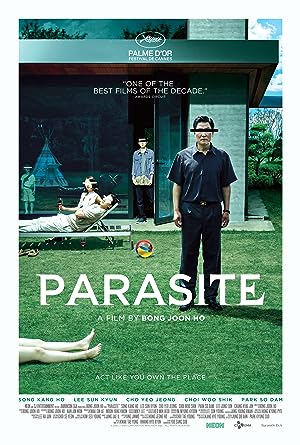

Parasite is the latest film directed by Bong Joon-ho, who is best known for Snowpiercer, Mother, The Host, Memories of a Murder and Okja, which I’ve been warned not to see because of my sensitivity to seeing animal cruelty. His work has only been getting better over the years so Parasite is no exception. It is about a close knit family of four whose fortune appears to turn after one of them gets a job with a wealthy family of four. By the end of the film, you will wonder who the real parasite is.

If I was planning a thematic film festival, and Parasite was the focal point, I would also show Shoplifters, Us, The Last Black Man in San Francisco and Burning, which apparently has the same cinematographer as this film, Hong Kyung-pyo. [Side note: Chang-dong Lee, who directed Burning, also directed Poetry, which I would pair with Mother.] It may be too much, but I would also consider showing Train to Busan although it is not at the same level of quality as the aforementioned films. All these movies address socioeconomic class issues in a visceral way that does not feel so removed, theoretical and intellectual as a professor lecturing to students about how economics and bureaucracies affect the average person’s daily life. These films set up a scenario that is familiar enough to be relatable but fantastical enough that a viewer can potentially reflect on the impossibilities of living an individual full, abundant life without noticing the impact on others. Movies create the illusion of omniscience so we can’t be oblivious to any plight but our own and also create enough tension for us to constantly hold our breath waiting for the other shoe to drop because we know that the characters’ existence as it is cannot be sustainable. The viewer has a few choices: pick a character, usually the protagonist, to empathize with and root for, empathize with no one, i.e. everyone is bad and had it coming, or empathize with everyone.

Parasite is a film with no single protagonist, and every character is unlikeable or flawed in some way. We are constantly shifting perspectives among the different characters, and it is not until a certain turning point in the film that the broader implications of these characters’ stories are grotesque because they are an extreme expression of the inequities in our world, particularly in South Korea. The signs were present from the beginning of the film, but were subtle because they are visually transmitted, not overtly a part of the dialogue. Joon-ho’s framing and camera movement throughout the film is excellent. Families’ status is equated with their perspective, i.e. the windows of their home. Our central family, the Kim family, is in a precarious position. No one would want their view, but at least they have a view. In contrast, the Park family live in a luxurious, sheltered house, implied to be high above their surroundings. Their employers’ view is full and spacious—it overlooks a garden, which has Edenic Biblical associations. They stand tall and can fully and comfortably occupy their space. The movement of the characters in the city is also key. The first scene on the street, the camera angle is tilted so the son is walking down to meet his friend, who is seated and stable. Our central family is in a precarious position, always going downward, rarely occupying the full frame unless huddled close to the ground. They are literally on a slippery slope.

As the film unfolds, Parasite demands that we question any aspects of our world that we take for granted. Parasite is more realistic and even more pessimistic than Train to Busan. There is no solidarity in oppression, only different levels of being dehumanized and acting as a living, breathing facet of an automated world that relies on your servitude and does not relate to you as a person with feelings, needs and ambitions. It also is a more pessimistic film than Snowpiercer, which at least created the possibility of creating a new system that could respect the humanity of the people within it by finding a way to break the system. Joon-ho depicts the most extreme moment of uprising that young adult men love to fantasize about when they discuss class warfare, but it only leads to misery for the have nots, not a redistribution of wealth. Soon the system returns to the status quo with no obvious indication that there was ever a struggle. It is easy to sweep things into the dark corners that are not illuminated by light, whether artificial or natural, if they are not wanted whether it is the undesirable history of conflict between neighboring family nations or unsuccessful people. The burden of guilt and responsibility rests on the shoulders of the Kims, the vulnerable, eroding symbol of the middle class.

Parasite feels like the neighboring sequel to The Housemaid, both versions, with a more suppressed sexual dynamic (if you prefer a more overt sexual dynamic, then the unofficial sequel would be The Handmaiden). There is no sexual desire for bodies, but over status and comfort. South Korean filmmakers are reimaging the gothic horror story by setting it in well lit, spacious houses, but instead of the supernatural, the real evil lies in the hearts of men. The most horrifying lines in the film is the telling of a ghost story in which the teller is completely oblivious that she condemns herself by subconsciously recognizing that her good fortune rests on the restless, trapped spirit of the less fortunate, and when her husband says, “We’ll call it love.” While the Kim family’s flaws are obvious and taken seriously, they, and other unfortunate characters, have a genuine love and a distorted sense of gratitude. The Park family seem incapable of genuine empathy and emotion for each other though they theoretically go through the motions. There is something spectacularly depressing about how the Park family gets their kicks when they are alone. They should be living fully, but they have no idea how to do so. This poverty of the soul is endemic to status. Those at the lowest rungs may suffer from Stockholm Syndrome, but they are capable of experiencing transcendence of the spirit and appreciating beauty, not just base desires that feed the body.

Parasite is not a perfect story. I found myself annoyed, but understanding at one character’s need to lie when it was unnecessary. I also had to suspend disbelief as the Kim family acted uncharacteristically two times. In spite of these cinematic contrivances, the entire two-hour twelve-minute movie is quite absorbing. The final wish of a member of the Kim family reminded me of a poignant sequence from Spike Lee’s best film, The 25th Hour. It is devastating because it will never happen, beautiful for its vision of a world in which redemption is possible and the resurrection and redemption, the defeat of societal death is a reality.

Even if you don’t like subtitles, I would still recommend Parasite. It is a beautiful, tragic and often horribly funny movie, but the outbreak of violence, though limited, is startling and stark. The dogs live. If you love South Korean films, you have to see it! Joon-ho is only getting better and is a real auteur.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.