Pain & Glory is the eighteenth Pedro Almodovar film that I have seen in my life. There are only three of his early films that I have not seen yet. It should be a requirement to see any of his films repeatedly before being permitted to credibly discuss how you feel about the film. The minimum number of viewings should be two. When I read a review of Almodovar’s most recent film after my initial viewing, I was horrified that it was more of a spoiler synopsis of the entire story without any warnings and without bringing any real insight to a reading of the film. I hope to do the opposite of that review. I will give a brief nonspoiler review then plunge into the deeper meaning of this masterpiece.

If you have only seen a handful of Almodovar’s films, or you have seen all his work, but you don’t “get” Julieta, I’m sorry, but you must not see Pain & Glory. You are simply not mature enough to understand his film, and you will be wasting his time and yours. It would be an insult to the soul of this man to watch it without being completely open to the experience and taking the emotional journey with no preconceptions until the lights come back on. Then you should reflect on it, see it again and think some more before uttering a word about what you thought about it. I’m not insulting you because I do all the following regularly, but see another movie even another artsy fartsy movie, a foreign film, a documentary or a popcorn movie if you are not prepared to fully digest and absorb this naked moment of the soul that he delivers on screen.

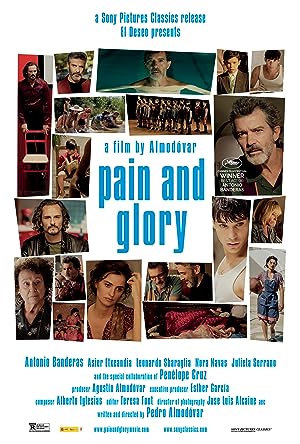

Pain & Glory is about a director, Salvador, played by Antonio Banderas, who can no longer work because of serious injuries to his body and soul so he is revisiting his first success thirty two years later, which takes him down a road that he does not want to be on, but he must travel in order to face his future. It is a colorful vibrant film that is more meditative and sober than the majority of his films. Banderas completely disappears and is reborn as Salvador. His physical demeanor is pitch perfect in the film. For a sapiosexual, on a superficial level, the living space of his character will fill you with joy. It made me think that it may be time to revamp my surroundings.

Whenever you watch an Almodovar film, you must ask whether or not what the viewer is watching is real or not. You must pay close attention to the narrative structure, transition points and the overarching thesis of the film. If you try to fit the story into well-worn tropes, you will miss the point so you should just stay home and watch a television show instead, which I enjoy doing so please don’t take this admonishment as a snooty insult. There is nothing wrong with that, but you should not be bringing that mentality to this story. This movie requires more of you because Almodovar had to give more of himself.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Pain & Glory is a secular come to Jesus movie in which the savior is work, i.e. cinema, and rock bottom is finally confronting the greatest pain and loves of your life. If you saw Destroyer, Almodovar employs an almost circular, ouroboros narrative structure, which is not obvious until the end of the film when you discover that all the scenes featuring Penelope Cruz are not actually memories, but scenes from a film, “The First Desire,” that he is making after he recovers from surgery and is prepared to start working again. It is no less shocking on an emotional level than the end of The Sixth Sense when you find out that Bruce Willis’ character is actually dead. The entire trajectory of this film shows how he was able to resume working again after he spends the entire movie dismissing calls to work again from two actors, his assistant/friend and his doctor. It is not a traditional love story. It is a story of the first and last film, first and last love/lust, but the real commitment is to himself as a creator and the ability of actors to be conduits to facing the truth about his experience as the creator.

Pain & Glory revisits numerous themes that Almodovar explored in other films: drug use, self- imposed exile from a parent because of sexual orientation, plagiarism as a potentially beneficial, life-giving act, difficulty in communication, the role of the city and the rural home village, bullfighting, filmmakers at the end of their career and mad men. Banderas is famous for playing some of Almodovar’s most famous mad men in Law of Desire, Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down and The Skin I Live In. Banderas as Salvador, who seems like a thinly disguised Almodovar, which I have never so clearly felt in any of Almodovar’s previous works, is one of Banderas’ most sane characters, but Salvador definitely has some deep unexplored issues and trauma. He only addresses these issues because of an event that occurs off screen: he sees a remastered print of his first successful film. We see two of four elements: earth in what appeared to be a tree trunk hanging next to a pool, water, which becomes a visual antonym of a baby in the womb, a scarred, floating Banderas. Because of an accidental encounter, the most crucial scene in the film, with Zulema, who holds the key to the film, “I can’t live without acting,” i.e. he can’t live without work, he would not be able to resolve his past with his present. Zulema is the key to living a full life as symbolized through her effective and rapid ability to facilitate communication. It is symbolized by her instigating their encounter, having everyone’s contact information, bringing people together. Without her, there is no movie.

The first issue that really provides the momentum and unclogs his constipated psyche is displacement anger issues. The early tension of Pain & Glory lies in his estrangement from the main actor of his first hit film, Sabor, because he didn’t like the way that he played the character that he created, but now he thinks it was a great performance. It is later revealed that his anger was actually rooted in heartbreak that the love of his life caused by taking the same drug as the actor. So the actor becomes the safe scapegoat substitute for the boyfriend. The actor later secretly plays the director in a theatrical performance, which the ex-boyfriend attends, which leads the director and the ex to finally fully discussing their past and present lives. It is a beautiful resolution of a chapter in three men’s lives that was unresolved for thirty-two years! Once it is resolved, Almodovar never shows the actor or the ex again.

Almodovar depicts drug use in films as self-medicating tools for people who are unable to cope with the pain of life. In this movie, one character characterizes it as “slavery.” Instead of the director and the actor dealing with their problem in their first reunion, they take drugs, which delay frank communication. The drugs make Salvador reluctant to work, i.e. attend an event, but because of an unanticipated, impromptu speaker phone question and answer with viewers, all their issues inadvertently come to the forefront because of unguarded communication in each other’s presence that was actually directed at someone else. Because Salvador wants more drugs, he offers his work to the actor to continue getting drugs, which results in the actor getting work and not taking drugs so he can put on his one man show that leads to the brief reunion/resolution with the boyfriend and Salvador, which leads to Salvador wiling to confront his pain and stop taking illegal drugs. Work is life, and life is pain. Once one works or is willing to face pain through frank communication, Almodovar suggests that illegal drugs are no longer necessary, and these extraneous conduits to resolution such as inquisitive viewers and actors can exit the scene once you face the real issue can be faced. Art leads us to ourselves, even when the creator of that art. In many ways, Pain & Glory is a thank you film dedicated to his actors and fans for helping him analyze himself. He is trying to embrace oblivion, and we won’t let him.

The second issue that he has to face is his mother’s death, which sounds fairly straightforward until you remind yourself that he has displacement and delay issues in dealing with his anger. Seeing Julieta before Pain & Glory will really help you understand the unspoken, subtle issues regarding sexual orientation being confronted in this film. All the flashbacks that are actually scenes from his movie post-surgery address when that death really happened. “Real” memories are depicted during interludes of conversations that he has with his friend/personal assistant/agent, Mercedes, about his mother, who is depicted as an elderly woman, not played by the glamorous Cruz, but by Julieta Serrano, who previously played Banderas’ mother in two earlier Almodovar films: Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and Matador (thank you, IMDb)! In Julieta, an oblivious mom does not understand why her daughter became estranged from her whereas it is implied that the daughter couldn’t deal with being a lesbian and decided to immerse herself in conversion therapy.

It appears that Almodovar was unable to confront two things before Pain & Glory that were extolled and depicted as taken for granted truths in his earlier films, but perhaps fell short in his own life: a close bond with his mom without conflict and the restorative power of returning to your home village. From Volver to The Flower of My Secret, daughters return home with or to their mothers, and the mother is reinvigorated and restored to life. It appears that Almodovar is ready in fiction to confess that he used films to console himself with images of the resolution that he wanted, but was incapable of giving or having in real life. Because of the issues that he worked out with the actor and his ex, he discovered that there were some things that he would not give up for love: Madrid or work. They are inexplicably intertwined, but Madrid is poison and death to the love of his life and because of her health, he couldn’t practically return his mother to his childhood home, but he also doesn’t want to. He chooses to put himself before others. He survives.

He denies it, but in a depicted memory, not a scene from his movie, his mother accuses him of deliberately distancing himself from her. She isn’t wrong based on his later apology to her, “I’ve failed you simply being who I am,” which is heartbreaking. She never tells him that he is wrong to apologize to her. She doesn’t deny that she wanted him to be someone else. Even though it is never explicitly stated, she hates that he is gay. If a viewer uses that conversation as the prism through which you reflect on all the scenes from “The First Desire,” you’re not watching some rose-colored view of the past, but the beginning of an epiphany of himself as a sexual being and a professional, which leads to a change in his relationship with his mother. They are close to torn apart. He knows what he isn’t: a priest. It was only at the second viewing that I noticed that he locked eyes with his first crush when he and his mom first arrive at the village. During the first viewing, I thought that we were seeing scenes lauding his mom’s ingenuity at getting free home renovations, which she is, but she is also supervising the lessons between the builder and her son like a hawk. It is actually his second time with the builder, who is depicted as heterosexual. When Salvador first touches the builder’s hand in their third encounter, it is a moment, not for the builder, but for Salvador. In their final scene together, the mother’s marked coldness at the builder, her son’s sudden illness and her expressed anger that her husband wasn’t home to watch over them indicates that she suspected something about her son before he was fully conscious of it. No one ever openly discusses what happened.

These conversations with Mercedes leads Salvador to another discovery: a portrait of Salvador as a child by the builder that his mom never gave him. It is implied that he is not only his first crush, but the builder is the first person that he directed and inspired to create. It is another delayed communication. Even though it is unspoken, Salvador intuits that his mother is an obstacle to his sexuality and his artistic ambitions. While she says that she doesn’t want him to be a priest, it is hard to discern whether her friendship with the “pious lady” is purely mercenary to get Salvador a better education, or if she drank the Kool Aid and was pious too, a barrier between his true church, the movies. She certainly is into rosaries at the end of her life, whereas the narration in his movie and the one-man play confess that prayer and love are ultimately inadequate in a way that work isn’t to address pain in the real world. This latest movie is his attempt to exorcise the pain of death-the death of their bond and her literal death. The one scene that is depicted two times in the movie is their closest moment in an empty train station. The first time it feels like a memory, but we don’t see the child’s point of view. The second time, we do, but we also see adult Salvador’s point of view, that it is a movie, not a memory. The child’s point of view is the framed sky showing fireworks, but it isn’t the first time that we see his point of view though it is the first time for the child. The first time that we witness this epiphany, a child seeing a framed sky, is when he enters his childhood family home, a cave, which has a frame of the sky in stone, which brings to mind the idea of Plato allegory of the cave and the projection of images, but instead of it falling short of reality, it is better than reality. Isn’t framing the sky like capturing heaven, and isn’t capturing heaven the spiritual feeling of a blank screen to project a film on? It is for me. The one man act that Salvador writes and gives to the actor is dominated with the idea of a wall to project movies on. The second time that the viewer sees Salvador look at a framed sky is as an adult in a hospital waiting room before he is given more hope. This final scene not only reveals a wistfulness of his former closeness with his mother and mourning her the minute that he began to lose her, but his first discovery of primitive film, the love of his life.

There is so much more to discuss about Pain & Glory, but I will devote the rest of my time to further epiphanies that Almodovar seems to be on the verge of reaching, but doesn’t. Salvador’s success comes with a lot of benefits that he takes for granted and misses the fact that it makes others’ lives more difficult. He wakes up Mercedes in the middle of the night to arrange his doctor appointments when he decides not to have drugs. His epiphanies are usually at the expense of someone else’s discomfort: the actor’s career may have suffered, his viewers did not get him to deliver his promise of appearing, his pupil never finds out that his art inspired him. This last one hurt me the most because he dismisses the idea of looking for him as ridiculous, but considering that his girlfriend ridicules his pupil’s artistic pursuit, if he was still alive or even if he wasn’t, for his family to know that his work mattered to one of the most important artists in Spain and perhaps the world, would have made a difference. Adulation is such a part of the air that he breathes that he takes it for granted and fails to recognize that many others never have that moment. Someone give him Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun to add to his library. A piece of art touched him, and he should not have scoffed at the idea of saying thank you in the real world. Others gave him life through his work, and he should pass it on.

Here is another depressing thought. What if you have the pain, the loss and no satisfying work? Salvador never commits suicide, but it feels like a possibility based on one book that he reads. Death definitely seems like an option, and by the end, the renewed home reminded me of The Farewell in many ways. He gets hope through his work whether inadvertently by someone else such as the actor putting in the effort to bring his words to life or directly by making films again. Maybe it isn’t Almodovar’s story to tell, but “without filming my life is meaningless,” and I would be interested if he can envision a story with no hope, a life filled with pain, no love, alone and no meaningful work. How does that movie end? I don’t think that he can. Someone always catches Salvador when he falls. He doesn’t do that for others.

I could relate to how Salvador lives in his head. I would randomly contact someone that I hadn’t spoken to in ages and act as if we had just spoken yesterday because I was inspired by a reminder of our last interaction. Yes, I know that it is weird AFTER it is pointed out to me how much time has actually passed, but at the time, it makes sense, and I think that the other person will recall that last interaction too instead of thinking WTF. He can do that because of who he is. Regular Joes and Janes should reject that impulse and become hermits. Sorry to bother you.

While Pain & Glory may not be my favorite Almodovar film, it feels like his most honest. Visually his transitions were seamless: piano playing, water, sleep. His narratives are like novels, which are making them more difficult to digest for newcomers or people expecting pure entertainment without a lot of intellectual heavy lifting, but old fans such as myself are intrigued by the continual evolution of his work. He always knows how to keep us guessing while working with familiar themes. I hope that he is far from making his last film.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.