I am notoriously hard on Christopher Nolan. While I enjoy many of his early films, he began to lose me with the dreckitude visuals and eyeroll inducing “Inception” (2010), which influenced “Doctor Strange” (2016). I recognized that “Interstellar” (2014) was just a reboot of “Contact” (1997) within the first five minutes and was resentful and bored as I predicted every plot point of the punishing remaining runtime. “Dunkirk” (2017) works in a vacuum but any basic understanding of history and Nolan’s objectives made it a failure according to his own definition of success. According to Kenneth Branagh, even World War II vets thought the movie was louder than the war. While I enjoyed parts of “The Dark Knight Trilogy,” I despised Nolan’s sound design and was done. In April 2022, when studios announced that “Barbie” (2023) would be released on the same day as “Oppenheimer” (2023), it was no contest. I would pay for “Barbie.” When I was fortunate enough to get a screening invite to both, I was receptive, but expected the worst.

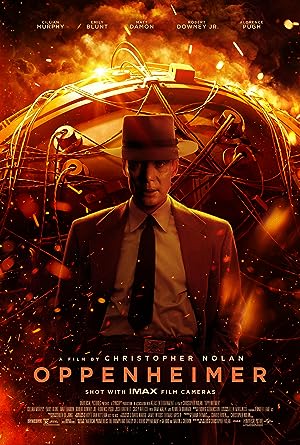

“Oppenheimer” is Christopher Nolan’s best movie. After going to the screening, I paid to see it in theaters again—a first for a Nolan film. I usually wait until I can get it for free from the library or on a streaming source that I already subscribe to. I even thought that the sound design was perfect and moved the story forward. It is a film adaptation of “American Prometheus,” Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s biography of the titular physicist, which I am now interested in reading. The film chronicles events that impacted J. Robert Oppenheimer’s adult life, including the Manhattan Project, a top-secret World War II project that developed the atomic bomb, which was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and his professional relationship with Lewis Strauss, who offered Oppenheimer a job at the Institute for Advanced Study. The two men later worked together at the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission.

“Oppenheimer” is a conventional story told in an unconventional way, which includes rejecting a chronological account. Nolan described the black and white section, called “Fission,” which means dividing something into two or more parts, as objective reality thus borrowing the aesthetic of a historical lens by mimicking older film footage for viewers to accept it as fact. The 1958 Senate hearings on Strauss’ nomination to Secretary of Commerce dominate “Fission.” Nolan also revealed that the color section, called “Fusion,” which means the process of joining two or more things together to form a single unit, is subjective, which is obvious since it often uses impressionistic images and distorted lighting to depict Oppenheimer’s inner life. “Fusion” focuses on the 1954 United States Atomic Energy Commission closed hearing which revoked Oppenheimer’s security clearance. Both hearings do not adhere to the rules of evidence or due process; thus, do not have the veneer of being fair and impartial, which is why the characters refer to the hearings as kangaroo courts. The decisionmakers have already jumped to a predetermined conclusion about Oppenheimer and Strauss. Both sections contain flashbacks because for each man, the hearing forces them to justify their life.

If the alternating film stock sounds familiar, it is because Wes Anderson’s “Asteroid City” (2023) used a similar technique, but Anderson’s story is fictional and experimental, not a cohesive story per se. Anderson’s film explores narrative structure and emotion whereas Nolan’s film tells a few conventional stories. It features the Hey, let’s put on a show trope. The Manhattan Project, which is the film’s focal point, is the show, but not the destination for this narrative’s journey. It is a character study of Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) and Strauss (Robert Downey Jr. embracing his inner Jeremy Irons), but the dominating trajectory is a character assassination story. Before I heard Oliver Stone praise the film and explain that he refused to adapt the biography, “Oppenheimer” felt reminiscent of “JFK” (1991) in the way that it examined all the seeds of destruction weaved throughout the timeline, retraced certain events, and flashed multiple events in different sequences to reveal the conspiracy. The character assassination storyline only becomes obvious in the last hour and felt like a more grounded reprise of “The Prestige” (2006).

I am not Jewish and was brought up as Christian fundamentalist, which I am not anymore, but part of my journey away from my roots was an emerging awareness of unintentional appropriation out of admiration. If I stray into this territory because of this interpretation, please feel free to call me in. Neither Nolan nor Murphy are Jewish, but Downey Jr. is in part. The story felt very Jewish because Oppenheimer and Strauss are Jewish and exhibit that aspect of their identity in different ways. Strauss is an active, open and proud Jewish man who identifies with a particular synagogue whereas Oppenheimer is secular, but identifies as Jewish, which is why he is so eager to join the fight against the Nazis and willing to sacrifice his other principles. He even notes with a measure of pride that the Nazis deride his scientific practice, quantum physics, as “Jewish science.” Here is where Strauss strays. When Oppenheimer first meets Strauss, he asks Strauss if he ever studied physics, which Strauss did not. An implicit divide is that Strauss has neglected an aspect of his identity by siding with politics and power, not physics.

In contrast, Oppenheimer respects Leslie Groves (Matt Damon), who is not Jewish, because of his educational choices, and Groves rewards Oppenheimer by protecting him from the Boogeyman (if you know, you know). I do not think that it is an accident that the character is based on a Russian descendent who literally killed Bolsheviks. I am not suggesting that the real-life person engaged in pogroms—or that anything discussed herein is referring to actual people that these characters are based upon, but when people fought against the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, it often acted as cover for pogrom-like activity, and many Russian Jews were killed. The subtext feels as if Groves recognized that Oppenheimer needed to be protected for a variety of reasons.

“Oppenheimer” felt like a journey into assimilation for Oppenheimer. Isidor Rabi (David Krumholyz), an avuncular contemporary, describes Oppenheimer as a prophet, and visually it makes sense. The “Fusion” portions show Oppenheimer’s visions, which resembled madness that he could suppress through action and community. Biblical prophets would often engage in bizarre behavior that hid a deeper meaning so when Oppenheimer breaks glasses and stares at water, he is theorizing. As he exposes himself to more of the world and verbalizes his theories, the visions disappear in the movie. Engaging with abstract art, going to different countries, learning different languages, working with internationally renowned scientists, and promoting political positions displaces his visions and anti-social behavior. His opponents later list these activities as proof of Oppenheimer’s communist leanings.

During their first meeting, Oppenheimer tries to deflect Rabi’s concerns about anti-Semitism and being accepted by asking if Rabi is referring to “physicists,” not the implied true meaning, Jewish people. When Oppenheimer befriends Ernest Lawrence (Josh Hartnett), Oppenheimer tries to get Lawrence invested in integration and unionization, but Lawrence succeeds in getting Oppenheimer to abandon his interests and “associations,” which includes his brother for a time. Guess what Lawrence does when Oppenheimer is in the hearing. Conditional support is always temporary.

To serve his country and fight the Nazis, Oppenheimer gives up a huge part of his community and a stabilizing, moral core to his life because it is deemed Communist, other, dangerous, anti-American. There is never an explicit moment that equates communism with Jewishness, but the Venn diagram between anti-Communism and anti-Semitism is explored in academia—the myth of the Jewish Bolshevik, which the real-life Strauss spoke against when it happened in Poland in 1919. While Oppenheimer is energized with his new work community, the foundation is predicated on shifting sand. Once the Manhattan Project is complete, he no longer has the stabilizing forces that made it possible for him to function in the real world and begins to experience dissociative auditory issues and visions of destruction. It is not just guilt, but a common phenomenon known to entertainers at the end of a theatrical run or prophets after engaging in a huge miracle such as Elijah after calling down fire from heaven in a competition against Baal’s prophets (think dance off for God vs god).

Here is where the Einstein connection works well. Oppenheimer asks, “How long have you been British.” Einstein replies, “Since Hitler told me I wasn’t German.” Oppenheimer is American until the US does not find him useful just like Strauss is only protected when he serves others’ interests, i.e. his country, not his ambition. Diaspora stories are fascinating and different. Even though Oppenheimer is multilingual, and Strauss appears to be wealthy and connected, they are less willing to move or blame their problems on a system of power that they did not create, but benefited from in part. They do not see their rejection and condemnation as a continuation of anti-Semitism, but attribute it to individuals, which is a reason why the US has fewer class solutions than Europeans. Americans consider problems and solutions as an individual failing and burden, not systemic in need of a collective solution. Oppenheimer and Strauss’ stories are two sides of the same coin. They are the scapegoat, the other, that can be cast out and characterized as the villain in any story even though they never acted alone.

After I saw “Oppenheimer,” I read how the last scene shocked everyone: a fearsome, deft rendering of Oppenheimer’s spirit possessing William Borden’s body in a B52 to witness Oppenheimer’s worst-case scenario of the Manhattan Project. Because I am a child of the eighties, “The Day After” (1983) and the Terminator franchise made a nuclear holocaust feel imminent, so it was not the denouement scene that I found most chilling. It was Einstein’s prophecy/warning to Oppenheimer of what would happen to him one day. As a story of power, the real horror lies in how the system discards the talented then forces them to participate in the horror of politeness as if they were never harmed.

Critics may not realize that for Nolan, “Oppenheimer” is his most revolutionary movie. The Batman trilogy was regressive AF, but the scary communists are mostly ineffective, powerless talkers who attend endless meetings. The jump scares are reserved for the anti-communists when Oppenheimer gets startled after noticing a cop looking at license plates, vague visual allusions to possible murders, a sequence showing all the people exiled from their proper work and of course, The Boogeyman. Nolan at least acknowledged that the US took Native American land, featured people of color in the background as extras and had a few women as scientists. The film allegedly represents Oppenheimer’s perspective, so it is horrifying that Native Americans are more theoretical to him than the quantum universe, and Hispanic Americans do not even exist. He fancies himself a modern-day cowboy and continues the myth of Westward expansion, Manifest Destiny. He acts as if the land is unoccupied, and he is its sovereign. It is gross and may be hard to stomach for viewers with a close, exploited connection to the Manhattan Project. While Nolan’s latest film does not pass the Bechdel test, and the two women in Oppenheimer’s life come off as emotional trainwrecks, a charitable interpretation could be that their antisocial behavior and self-medicating could be a result of being a woman in such a restrictive, gender normative society that did not value their brilliance, only their relationship to Oppenheimer. Kitty (Emily Blunt, who is very Sarah Paulson in this role) gets a couple of terrific scenes.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Strauss had multiple grievances against Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer is a class snob who remarks on Strauss’ humble shoemaker origins. The film implies that Oppenheimer came from more affluent origins. Oppenheimer also was passing and a bit uncomfortable when a fellow Jewish person remarked on his origins. The educational divide sealed the deal with Oppenheimer in the lead, but Strauss was unwilling to accept the L. That gap in education leads to their disagreements about isotopes and H bombs. Overall if Strauss hated Oppenheimer, it was because Oppenheimer rejected Strauss’ social rules by openly disagreeing and ridiculing him. The most devastating line for Strauss is considering that he is unimportant. Nolan’s film was accurate that all the women and lawyers would warn Oppenheimer when he transgressed on this rule. Strauss plays as if he can handle slights with good humor, but he is stewing the entire time.

A lot of the tension and suspense in “Oppenheimer” is derived from the health of the relationship between two people. For viewers unfamiliar with the story, it is a plot twist that Strauss hates Oppenheimer. During the testimony, the film teases the possibility that Kitty will throw her husband under the bus for cheating on her, but she rides to his rescue and has a victory of sorts over the board. David Hill (Rami Malek), a Chicago based scientist working on the Manhattan Project, whom Oppenheimer behaves rudely to during every encounter, surprises Strauss by testifying against him and siding with Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer chides his lawyer, “A fool or an adolescent presumes to know someone else’s relationship.”