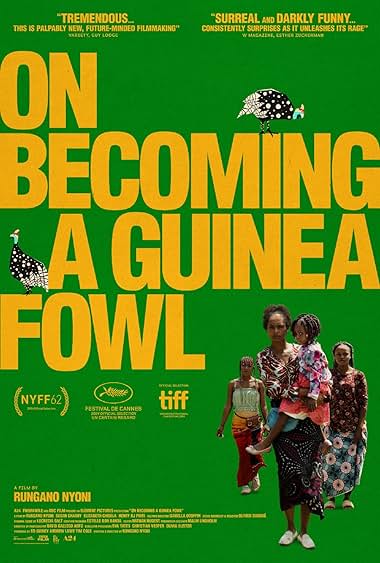

Believe the hype about “On Becoming a Guinea Fowl” (2024), director and writer Rungano Nyoni’s sophomore film that never slumps. After coming home from a costume party, Shula (Susan Chardy) notices Uncle Fred (Roy Chisha) lying in the road. Despite trying to return to normal contemporary life and distance herself from the funeral rites and family drama, her family sucks her back in through obligation and demand that she participates enthusiastically in mourning her uncle and act as if she has feelings. Shula starts off as resistant as stone then slaps on a veneer of obedience just to sneak away for stolen moments from the proceedings as more people arrive and fill the house and grounds. Eventually she thaws out and lets her true emotion arise. Be careful what you wish for.

“On Becoming a Guinea Fowl” is set in Zambia. Even though a lot of the dialogue is spoken in English, there are subtitles to translate the Bemba language portions and aid while becoming accustomed to accents. It is the kind of story where everything is unfamiliar because of the location, the unique story and structure, and unfamiliar culture if you were born in the US. There are oneiric sequencies—some dreamed and others real. If you find yourself asking why a scene is being shown or what is going on, have no fear because all your questions will be answered. Questioning your environment and the onscreen actions is the key to understanding the story, and the movie exercises that muscle so long after the credits roll, you can continue to develop it.

The onscreen family is well off. Shula is the kind of person who can whisk herself away to a hotel or reflexively and effortlessly dispense money whenever asked. She lives in her mother’s rural isolated house on a gated property with land and no close neighbors while her mother is in another city. Shula is a specific type of woman: professional, elegant and reserved while suppressing her authentic thoughts out of obligation, respect and habit. She is contrasted with her cousin, Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela), who is constantly drunk, but good natured, spontaneous and slow to anger—hiding her emotions underneath a layer of good humor. These opposites act as guides to this world since it is largely unfamiliar, especially as their family pressures them to follow an obligation that they clearly want no part of. It is not enough that Shula and Nsansa try to stand apart and move on. The women in their family demand that they enthusiastically follow assigned roles, and soon it becomes obvious that their different personas share the same roots—not family, but a childhood incident that is a silent rite of passage.

A lot of movies tell more than they show, but Nyoni’s film shows and makes you feel. The chief mourners are the older women in the family. They critique Shula’s performance and keep everyone in line. While watching “On Becoming a Guinea Fowl,” ask yourself questions. Which people are allowed to fall short and have their flaws overlooked? Which people must be perfect or have their perceived shortcomings magnified? Whose pain matters more? Which pain is allowed to be expressed? Which kind of pain is worthy of being expressed after death or shelved? What are people allowed to complain about? Who gets to rest and cry? Who must work and serve? Who benefits from the funeral? Why do people work so hard to comply with custom if they do not benefit from it? Which words get heard, and which ones are somehow drowned out and impossible to understand yet when it is silent again, still not given the floor? This movie would make a transcendent double feature with “Seven Veils” (2023) with this film being the superior of the two. Do not be surprised if your audience audibly reacts with outrage on behalf of the two women. Shula, just say no!

Chardy delivers a masterclass on how to convey a range of emotions while being muted and often inscrutable. Her collaboration with Nyoni’s visual language adds unspoken texture into the story that dialogue could not convey. A lot of scenes obscures women’s faces either by having them back the camera, through object blocking, wearing masks or light shining behind them. During these scenes, it can be obvious what the character is thinking, but Nyoni holds something back to communicate that some things are private to the individual, a mystery to even the person possessing those emotion, and cannot be empathized with even if there are attempts to lay it out.

The cousins’ turning point happens when they realize that they are a triptych of pain, drafted mourners. The third is Bupe (Esther Singini), a college student who needs a ride to get to the funeral but would prefer to stay in her dorm. Bupe seems to jar Shula and Nansa out of their coping mechanisms and radicalize them though there is a lag in the process. For Shula, it takes her on a journey to learn more about her uncle and his much-maligned widow, who seems to be bearing the burden of Fred’s sins. The Venn diagram between being kept busy so there is no time to think and a breaking dam of emotion would be a circle. Suppression never works, and the only way out is through when it comes to emotion. Keeping women busy and perpetuating that cycle while simultaneously loudly demanding that everyone must honor someone over themselves even in death is internalized misogyny.

Nyoni’s solution to breaking systems of oppression is not to run away. It is to find your equivalent voice in nature and imitate it. With a title like “On Becoming a Guinea Fowl,” this surreal resolution is unimaginable, and in lesser hands, would feel absurd and even risk undermining all the care that came before. Water is another natural symbol that emerges after encountering Bupe. A thick layer of water lines the dormitory building’s floors, but no one seems alarmed and just moves it around. It echoes the busyness of funeral activities at home. Was there a flood? Are they washing the floors, and it is just another routine? It is never revealed, but that water drills itself into Shula’s unconscious in dreams and floods her home. In her waking world, people sleep and dance in empty pools and fountains. It is about the damn breaking for some while others self-medicate to keep the truth from affecting them, but it leaves them leading an unnatural arid life. Water is destructive in certain spaces, ultimately life giving and can clean away the dirt. Without it, the structure is solid, but not functional, kind of like this family.

“On Becoming a Guinea Fowl” may feel like a daunting task when you just want to relax and watch a movie. It is a funny movie despite being about death and trauma, but more importantly, it is unique, stunning and surprising. A lot of great movies are coming out this weekend, but at best, they feel intimately related to a line of movies that came before or at worst, obliviously derivative and thinking that remixing parts makes a story fresh. Nyoni’s movie is hers and fresh. It is not often that moviegoers get a chance to see a movie that is unlike anything that came before.