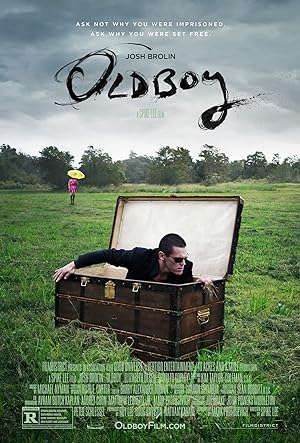

If you have never seen Oldboy and must see every Spike Lee movie, then I would recommend first seeing the American remake by Spike Lee then the original South Korean film by Park Chan-wook. Spike Lee’s Oldboy isn’t awful, but he has an impossible task. It makes more sense to remake a crappy film than a well-known magnificent one with subtitles.

Spike Lee’s Oldboy makes more movie sense. His main character is a bit of a bastard and loser. The television broadcasts during the confinement scenes had more American cultural resonance for me as a viewer: George W. Bush, Hurricane Katrina, Obama being sworn in, etc. The main character’s hallucinations and psychological suffering from being alone is more harrowing than the sequence of repeated failed suicide attempts in the original. His time in solitary confinement is more clearly fleshed out, and to apparently only me, it made more sense how this man can kick ass after he is free. The woman who helps is practically a staple of cinematic characters: the sympathetic woman who inexplicably decides to drop everything and help the mysterious man of action. Spike Lee’s Oldboy has more amazing colors, and the characters accessories and clothes are clearer markers of class and standing than the original. If the original cinematic Oldboy didn’t exist, Spike Lee’s Oldboy would be a solid psychological thriller and action movie that you would shock you.

I felt compelled to rewatch the original immediately after watching Spike Lee’s Oldboy, which suffers in comparison. The original story is emotionally and thematically richer and and more devastating than the remake. The characters are less like comic villains or heroes, but tragic figures in their own right. The action sequences are shot better. The original had me constantly questioning why the hell the woman kept helping the nameless main character, and their post-coital interactions hinted at their real relationship more convincingly than the remake.

SPOILERS FOR BOTH FLIMS

In the original, opposite sex, underage teenage siblings with little to no discernible age difference enter a consensual, but taboo romantic and sexual relationship with each other. The main character unintentionally spreads a rumor throughout the school about the sister’s sexual relationship with another teen. The sister commits suicide despite her brother’s best efforts to stop her. The brother wants the main character to know what it feels like to lose someone you love even if that love is wrong, but ultimately shows mercy by not revealing to the inexplicably helpful woman that she is the main character’s daughter.

In Spike Lee’s Oldboy, the situation is completely different. Even as teenagers, the villain and his deceased sister were eager and consensual victims of their wealthy father’s sexual abuse. The main character accidentally saw the sister having sex with an older man, didn’t know the older man was her father and intentionally ridiculed her around the school as a slut. Their father withdraws the siblings from school, kills the villain’s mother and sister, attempts to kill the villain then commits suicide. The villain wants the main character to know ultimate love then have it taken away with the awakening that this love was wrong.

If I’m feeling generous, the literal parallels in Spike Lee’s version make slightly more sense because the villain’s father and sister can be directly compared with the main character and inexplicably helpful woman, who are also, albeit unwitting, father and daughter. Unfortunately I’m not feeling too generous. Lee confuses taboo and shock with abuse. As repugnant as it may be to most viewers and as ill advised as it may be genetically, in real life, though (hopefully) rare, brothers and sisters have entered consensual relationships where there were no obvious unequal power dynamics such as age differences.

The same cannot be said for biological parents who raise their children and sexually abuse them. Not only is consent impossible, but the children are usually psychologically damaged and not enthusiastic about the situation even when they physically submit. Lee doesn’t understand what makes the original Oldboy tragic or the psychological profile of the original villain, particularly his pathology, so Lee fails when he attempts to replicate it and conceive of why the villain felt wronged and what the villain would consider a suitable vengeful act.

Most alarmingly, Lee inadvertently revealed that he fails to understand what abuse really looks like, which is why his definitive image of redemption, though satisfying in terms of a tidy ending, does not have the same impact as the original’s ambiguous and unsettling image of redemption. Lee goes for the Hollywood ending, but Oldboy is about tragedy.

Even if you didn’t know it, consensual or not, you can’t sleep with certain people and escape unscathed physically or psychologically. After the original main character discovers the truth, the original shows the main character’s body repeatedly shattering glass. He begs, abases and maims himself to appease the villain and in the end, becomes a mute with a memory that may or may not be altered as he shakily gazes into the sunset. Lee’s end feels more like a denouement as imagined by a Bond villain.

After watching both versions, I found out that the theatrical release differs from Spike Lee’s original cut, which was thirty-six minutes longer. Maybe the director’s cut is the equal to the South Korean original, but unfortunately, I just don’t know. Spike Lee’s Oldboy is a solid shocker, but lacks the depth and nuance of the original.