I generally don’t enjoy Lars von Trier’s films, but I genuinely believe that he is a sincere artist so I wait until the last possible moment to watch his films. I don’t think that I have ever paid to see one of his films and stopped requesting them on DVD even though I keep them in the queue because it somehow seems too affirming to physically bring his movies into my house. When they are available to be streamed, I put them in my queue and wait until they are about to expire to watch them. Sometimes I’m delightfully surprised with films like Melancholia, and other times I can appreciate the film while simultaneously finding it repulsive with films such as Antichrist. Otherwise normally I’m just repulsed and horrified with films like Breaking the Waves or Dancer in the Dark.

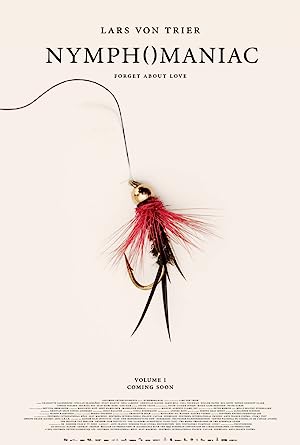

Being an almost compulsive completist has its disadvantages. A film called Nymphomaniac Vol 1 and 2 is daunting even for an artsy fartsy film lover as myself who has a high threshold when faced with shock value, but is also not a porn consumer except in circumstances such as these when a film comes under the radar as primarily an art house film, not for titillation. I can probably count those instances on one hand with fingers to spare. I waited over three years, until August 2, 2017, to see the theatrical version of Nymphomaniac Vol I and 2, which is three hours and 40 minutes and was dismayed to discover that there was an Extended Director’s Cut, which was six hours and twenty-six minutes long. I was unable to make myself watch the longer version until December 22, 2017.

Nymphomaniac is a conversation between Seligman, a man who seemingly rescues a beaten woman, Joe, who is a self-professed nymphomaniac. When she talks about her past, the movie depicts what happened, but as Seligman or Joe interject with tangential observations, von Trier overlays the depictions with their concepts or segues to depicting their imagination. If I began to grasp the deeper significance of the film during the initial viewing, my conclusions evaporated as the minutes dragged during the second viewing. Though I think the additional scenes give viewers a fuller understanding of the story, Nymphomaniac does not improve with multiple viewings, and I actually felt that the additional scenes completely altered my impressions of Joe from an unrepentant militant to someone hoping for a more conventional view of redemption. I’m not sure if this shift was intentional or a flaw in my recollection.

Nymphomaniac is more in line with von Trier’s pessimistic theology as originally reflected in his earlier films such as Breaking the Waves or Dancer in the Dark, but his later films have bucked against his instinctual impulse to make women the Jesus figures that die to redeem mankind. It is an oversimplification to say that he is a misogynist, especially since his later films reveal a John Updike disgust over men. His entire perspective is jaundiced, and women are depicted as more three dimensional than his men. His view of humanity and theology is distorted so to understand his work, the following exchange can act as a guide. Joe says regarding judging her story, “Perhaps according to a religion that doesn’t exist yet or a god that hasn’t manifested himself.” Seligman responds in slight horror, “Then you can imagine anything.” She proceeds to resume the beginning of her story.

Nymphomaniac reminded me of The Sunset Limited. Both films take place primarily in an apartment and involve two strangers, a Good Samaritan and an unwilling rescuee, who then debate whether or not life has meaning. In Nymphomaniac, the characters do not adhere to any religion. Although Seligman has Jewish ancestors, his home is filled with Eastern Orthodox icons, and his Bible is The Compleat Angler. Joe insists that she is a sinner, and her Bible is a journal whose pages are filled with leaves from trees, her Herbarium. They are eager to use fishing as a metaphor, and Joe is literally a fisher of men. She walks with her father. She experiences a transfiguration. On Christmas, she chooses the church of happiness by prioritizing her pleasure, which happens to be suffering.

If the religion does not exist yet, then they are desperately trying to discover it, and Joe may be a leading figure in its story, another of von Trier’s Jesus figures who rejects sacrifice. They use stories and knowledge to impose meaning on their lives, which mirrors the apophenia of the viewer. Seligman seems to provide sober, objective reflection on reasons why her behavior is not sinful, but Joe is annoyed by his excuses.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Joe only has a handful of real relationships: with her father, who dies, her friend B, who rejects her, and Seligman, who betrays her. I found it intriguing that even though she is instinctually hostile to psychologists, she eagerly shares her story with Seligman. For me, the most shocking moment of the film is that Seligman is actually awful, and all those hours are just an act for him. Despite all his words, he does not see her as a human being wronged because of her gender and sexuality. She is an available vagina. Even though very few people would cosign Joe’s extracurricular escapades, she still has her autonomy, but Seligman’s attempted rape is the most shocking moment of a film that relies on excess because it is a profoundly depressing moment, and it reminds us that the perspective of the men in her life may be similar thus detracting from her power. If Nymphomaniac is powerful, it is how unswerving it is in sharing her perspective and belief system, which reduces the men to pieces of meat who are exploited. To remember that the world does not work that way is an abrupt clash of wills, which she naturally wins. There is a triumph, but it is a pyrrhic victory. It is almost as potent as her throwing a Molotov cocktail like a guerrilla in an unofficial battle of the sexes.

Joe is alone, cannot rest and has lost the sole comfort that she was able to retrieve that night—at least she isn’t a murderer. To be fair, I don’t think that she is a murderer in the truest sense of the word. She acted in self-defense. von Trier and Paul Verhoeven are very adept at defining what is and is not consensual. Even in a film filled with unsimulated sex and a nymphomaniac, rape exists. I wonder if this film is vaguely anti-Semitic in the way that Seligman is an unexpected sinister figure, but I’ll defer to others on that issue. Somehow it is even worse than the brutal and demeaning attack in the alley, which while excessive, is understandable since she did attempt to kill someone though resisted temptation and on some level, probably accepted the physical abuse given her dabbling in masochism, and it was her last chance at contact with the people that she loved.

Nymphomaniac is consciously derivative of his earlier movie, Antichrist, and reminded me of films like We Need to Talk About Kevin and Suffragette in terms of Joe’s relationship to her son. Charlotte Gainsborough is one of the few actors who has worked with von Trier in multiple projects, but this film is so stylized and long that I can’t conceive of deriving anything other than intellectual pleasure from it except the scene where they are in the movie theater, and she is disgusted by everyone pairing off, which did make me laugh. There is a neat triptych towards the end of the first volume. I had problems taking Shia Laboeuf seriously. Other than being her first, why would anyone be into Jerome? I loved the scenes between Gainsborough and Willem Dafoe, and out of context, it seemed like a natural visual conclusion to her early days with The Little Flock. Christian Slater’s performance was surprisingly touching, but the accent kept threatening to take me out of it. I loved the concept of a soul tree and suspect that mine is a banyan tree. Connie Nielsen clearly has a lock on disapproving, cold and distant mothers. It was interesting to me that neither Seligman nor Joe noticed the similarities between Joe and her mother once she became a mother. Also Jerome becomes like Mrs. H on Christmas. Jamie Bell’s performance was an unpredictable, but solid mix.

For the most part, the film repulsed me for all the obvious reasons. Poor Udo Kier in Melancholia and Nymphomaniac. Those aren’t your spoons! The main reason that I am reluctant to see Dogville is because von Trier already has a demented view of humanity so adding race to the mix may make me give up on watching his films entirely. He already has a fairly bleak view of the world so racism would be the cherry on top except not. The dangerous men are dangerous because? Oh, they are black and foreign. Who actually physically hurts her? If your reply is every thing is awful, yes, it is, but now it is getting dangerous given the world that we live in.

Nymphomaniac is mostly numbing and tedious, but I did feel something for Joe despite her flat inflection. Even though I understand how she got here, I actually don’t. Her relationship with her father shows that she is capable of relating to people in a healthy way, but on some level chooses not to. Is it really possible not to be a functioning nymphomaniac? She has zero relationships with women. I don’t think that we’re getting the whole story by just focusing on her lifestyle or her addiction depending on your perspective. von Trier made that choice, and I don’t think that it worked as opposed to the other movies in the Depression Trilogy, in which the suffering characters are set in a broader, objective story outside of their despair. If Melancholia is set during an apocalypse and Antichrist is set during a supernatural horror second coming. I don’t think that Nymphomaniac adheres to same standard and suffers because of it. If I had to theorize, she is the second coming, a reprise to Antichrist, the one who can face the gynocidaire and win. Or it can all be a bunch of crap that I mistakenly believe is art.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.