SPOILERS AND TRIGGER WARNING: SHOULD NOT BE READ BY SEXUALLY AND HISTORICALLY SENSITIVE READERS. PSYCHOLOGICALLY DISTURBING.

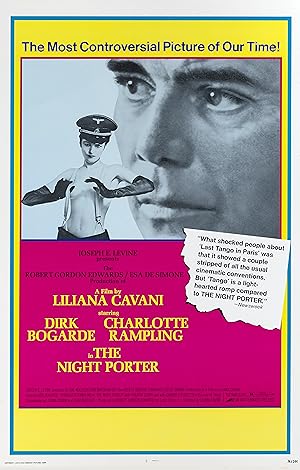

There are some films that you shouldn’t see until you are a seasoned adult with the ability to think reflectively and not get distracted by seemingly prurient and exploitive elements of The Night Porter. I decided to rewatch it soon after watching In the Land of Blood and Honey because I had very little memory of it except a vague sense that it was better than Jolie’s directorial debut. The Night Porter is a psychologically violent oneric film. This film starts off normal. Coworkers are engaging in their passive aggressive routine and duties, but as The Night Porter unfolds, I realized that words and actions that mean one thing in the normal world mean quite another in this Vienna. As we descend into one layer of this world, we discover that the hotel’s decadent guests and workers are trapped in their individual worlds of sexual fantasy and/or recreating the past which Max, the night porter, facilitates. As we descend to the next level, we see a tiny Nazi cabal discuss trials, but nothing like the Nuremberg trials. They are trials to examine what they did then eliminate the evidence-to be found guilty then freed. They don’t want to be found not guilty, but they do want to live the lives of the not guilty. Every one, except Max, wants and gets their moment in the spotlight or to perform on stage. He prefers to direct and stay behind the camera. He is like a vampire-he prefers the night and hisses at any potential exposure. When Lucia, which means light, a former concentration camp survivor, the daughter of a Socialist, one of Max’s former victims, and wife of a famous American conductor appears as a guest in the hotel, then you confirm that we’re completely through the looking glass. I think that the nationality of her husband and Vienna, the setting of The Night Porter and birthplace of Nazism, are important. Obviously German culture pre-1930s, especially Mozart, taken in its original context should not be equated with Nazism, but post-1930s, the association is contaminating. The co-author of a recently published book which I have yet to read, Stephan Templ states, “But the truth about our Vienna is that all the biggest attractions in Vienna were looted from the Jews.” If an American conductor enters an artificially Aryanized city with a wife who survived a concentration camp while playing German music in a vacuum of beauty without acknowledging even the possibility of a weight of history and prejudice inherent in his cultural and touristic activity, then that willful ignorance may mean that the American will be able to escape physically from the obvious terrors and traps, but those who can’t, which includes his wife, won’t-at least not without outside assistance, which never comes. He will suffer implicitly, but his suffering is not central and is unseen because it comes after nothing can be done. Once Lucia and Max meet, any sense of normalcy is eliminated, and if Chtulu appeared, he would be horrified. Initially Lucia tries to avoid this world, but even in the act of seemingly innocuous shopping, Lucia reclaims her role as Max’s then victim now lover. The Night Porter is interspersed with flashbacks from all the characters. Lucia’s longest initial memory is intercut with her husband’s performance of Mozart and her glancing at Max who sits behind her during the performance. Her fellow concentration camp prisoners are huddled and seated against the wall staring. The camera follows the direction of their stares to the center left where a naked Nazi guard is incessantly humping an unseen prisoner. [I am puzzled why most commentators claim that it is a male prisoner when usually Nazis segregated prisoners by gender, and everyone in the room who was’t a Nazi was female. I conclude that the prisoner being raped was female, but everyone else thinks that it is male.] The camera then pans to the center right where Lucia is lying in bed catatonically-she isn’t asleep, but she shows no emotion as she watches this horror. She has become inured to the horrors of camp life, but because of her position in the room, she can also be seen as waiting in the wings. Suddenly Max roughly touches her, makes her rise and leads her to the door. There is no question that he singles her out for rape, and that it is rape. In these initial flashbacks, her face registers reluctant acceptance but puzzled horror as she gradually realizes what is expected, but in this perverse world, to be chosen for a unique, individual and set apart torture as opposed to a mass, nameless, faceless torture is an honor. In Awful Normal, a documentary about a family of adult survivors of incest, one woman described the daily horror of her childhood, but also said that she had her first orgasm with her father. How does someone who survives such an abnormal adolescence as Lucia react when exposed to a seemingly cultured and civilized world that actually hides a seedy underworld of guilty exoneration? She chooses to stay. Even for this film’s insane Vienna, this action is too much, and incomprehensible even to Max’s Nazi fantasy bound friends. Why? Because Max and Lucia’s fantasy is much closer to the reality of Europe-instead of pretending that life is exactly as it was pre-1930s, Lucia and Max do not erase the collective madness of the 1930s and 40s. The Nazi friends and American conductor share one thing in common-they don’t want to dwell on the natural implications of what has happened while reveling in the past, but Max and Lucia want to continue on that road uninterrupted. What does it look like every day in a primal sense if you continue in the role of torturer and victim? They create their own prison. She punishes him by trapping him in an airless world that psychologically she never left. He is no longer the director of other people’s fantasies, but trapped in his own because he is now free to live the life that he always wanted to live. And as a Nazi who does not want to let go of his “little girl”-yes, he is a pedophile, and Lucia was clearly a young teenager when he picked her–or be free of his past and engage in a “trial,” he embraces her sentence and preserves the truth of his horror. She resumes this historical path for vengeance and pleasure at being seen, a living witness. When he says that their love is Biblical, he does not see Herod as the villain, but the hero. Words no longer have the same meaning that we are used to. Seemingly innocuous and tertiary characters suddenly take on the role as the Nazi friends’ enforcers to eliminate them. The Night Porter asks which world is more horrifying: a Vienna that wants to resume its pre-WWII glory by erasing or ignoring the historical horror or a Vienna that embraces its Herodian side.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.