A character is essentially asked how he knew to leave before the wall was put up, and I silently answered, “I didn’t.” How can an over three hour, German subtitled film be so riveting and relevant that the title seems less like a threat and more like a description of how a viewer feels while watching it? I didn’t feel hunger, restlessness or need to take a bathroom break. Never Look Away is Germany’s answer to Guillermo del Toro, a realistic magical realism filled with the historical equivalent of ghosts and vampires that need to be avenged and exorcised respectively.

I don’t think Americans really appreciate what it was like to emerge from the Nazis in World War II only to be occupied by Stalinist Communists. How do you survive decades of oppression that demands enthusiastic suicide for the nation? The answer is that most people don’t. Never Look Away charts two people’s successful journeys through three political ideologies: Nazism, Communism and Modernism—yes, this movie presents art as a political ideology. Those two people are an artist and a doctor. When we meet the doctor, he is at the height of his career, and when the movie introduces us to the artist, he is a little boy. Because they live in the same region, it is inevitable that their paths will cross, and I fully expected when that would happen, but that is where my prescience ended.

Never Look Away never depicts the conventional resolution that feels set up in the tragedy of the first act. Instead it initially feels like a coming of age film with a historical backdrop threatening to overwhelm and dominate the individuals within the story, but eventually they take center stage in the story of their life. The tone shifts in this movie are gradual, but effective until a mood dominates and feels impossible to shake off. The closest analogy that I can make is that this movie leaves the viewer with the same sense of awe as A Prayer for Owen Meany strikes its readers. It creates a way for human beings to unwittingly become the hand of God and cast judgment on the wicked. It is an extremely Biblical movie referencing being naked and unashamed, Biblical principals of marriage with the husband clinging to his wife and being one flesh, murdered blood crying out. It has a very Davidic Psalm sense of outrage that the wicked often prosper and the righteous suffer.

Old Testament prophets had more in common with performance artists and other creators than most Bible thumpers would care to admit. I love that Never Look Away feels as if it nails what it must have been like to consume and appreciate art during the Nazi reign and Stalinist Communist occupation. How would you know what to like if you were constantly told that certain tastes are degenerate and wrong? I’m always impressed that people are able to ignore what they are told and imagine out of thin air the path that best suits them then breathe life into their creation. The instinctual denigration of modern art can be heard in less ideological terms now, but is still strikingly similar. It wasn’t until my twenties that my eyes opened, and I was even capable of being receptive to any art that wasn’t over a hundred years old. The movie does not flinch away from showing that not all repressive political ideologies about art are wrong. Sometimes art is about consumption, capitalism and meaningless. It viscerally helps us empathize with the artist’s problem: how does one express oneself once you finally have freedom? What is the value of art? Freedom can be just as dangerous and soul killing if it erases the self in service of anything that is not true. It is difficult for an artist to eliminate all outside influences. As Bill Cunningham wisely wrote, “This was to be the hardest lesson, that of throwing off outside influences and making definite designs of my own.”

Never Look Away suggests that art is at its most powerful when it is inexplicably true and on some level, biographical, even when the artist is not fully cognizant of the story that he or she is telling. The artist is subconsciously sensitive to a higher frequency, which is why those who are powerfully struck by a work often take away a meaning that the artist may not have (consciously) intended, but was transmitted nevertheless. The power of art as restorative for the individual who makes and consumes it resonates with me. This movie succeeds at depicting the impact that even the most seemingly nonsensical or benign image can have on its viewer and creator when it is unique and meaningful to the one that created it. The space inhabited by art as it is being consumed and created is holy ground, and even my fumbling attempts to explain the inexplicable are not as distant as I would like from the oversimplification and reductive dismissal by oppressive interpreters who seek to create a rational distance from the fear of God.

If I seem maddeningly vague about the story of the artist and the doctor, it is because I really want you to see Never Look Away, discover the story and judge for yourself then come back and read this review. A family relationship becomes emblematic of the Motherland abused by those who love themselves more than the natural duty owed to others and violate oaths until the very future of the German people seem close to extinction. Even though I am grateful that the filmmakers treated the viewers as if they were smart and did not spoon feed us dialogue to explain everything, I still have so many questions. It felt as if the movie cut a lot about the doctor’s wife and daughter or decided that openly discussing the family dynamic would detract focus from the central character.

Never Look Away vaguely reminded me of Nosferatu. I loved the depiction of a realistic vampire-dark, vain, prosperous, immune to harm, feeds on those closest to him, afraid of exposure to the light and incapable of seeing his true reflection. When he enters the West, he seems like an evil Trojan horse slowly worming his way through society and trying to infect it after he had already spoiled his own turf. There is a delight when he swans into the studio as if he owns the place. Like any devil, he is happiest when he is trying to destroy God’s work. “What God has joined together, let no man put asunder.”

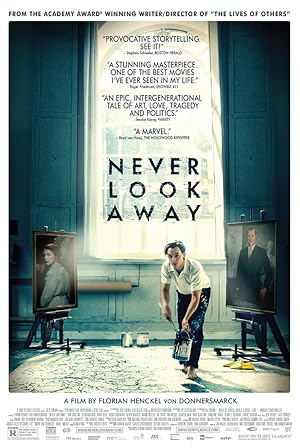

Never Look Away is heavily inspired by the paintings and life of Gerhard Richter, who despises the film. I am a fan of his work, and perhaps I would not have seen this film if I had known about his disapproval. The film never uses his name so you wouldn’t know until the denouement and only if you were familiar with his work.

Never Look Away was a transcendent viewing experience from a year full of amazing movies yet still manages to stand out from the talented crowd. I did not expect that a period piece about such horrible times could feel so redemptive, but if you hate modern art, you may not get it.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.