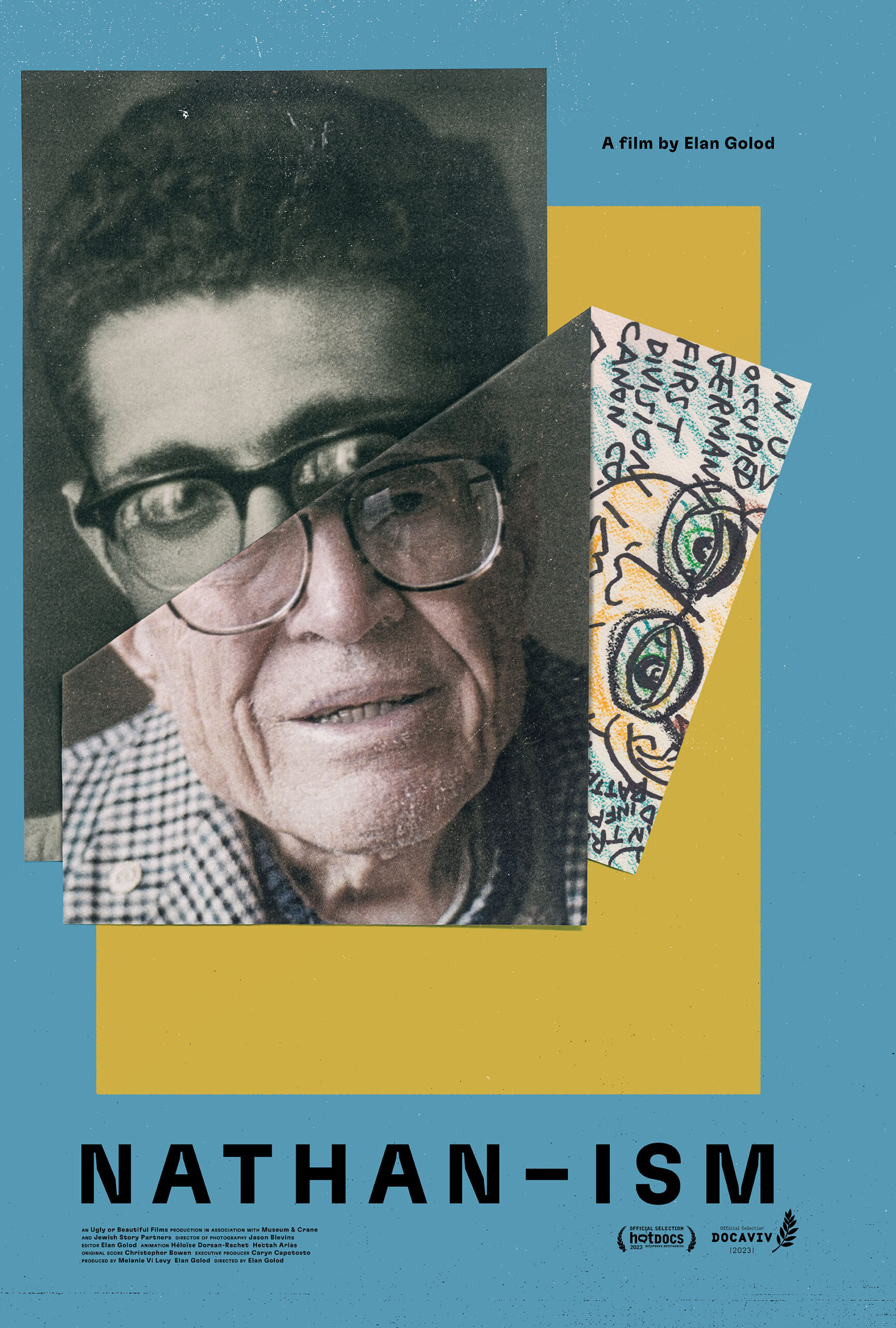

Shot from 2015 through 2019, “Nathan-ism” (2023) is a participatory documentary where first time feature director Elan Golod interacts with Nathan Hilu, a Syrian Jewish American World War II veteran who guarded Nazis during the Nuremberg trials. Golod also consults with others who are investigating the veracity of Hilu’s claims or are experts on that era. Hilu, an outsider artist who works in marker, crayon, Scotch tape, Elmer’s glue and other accessible drawing materials, is a willing participant in Golod’s film, but refuses to pin down the details of his accounts yet feels compelled to seek the attention. Where is the line between history and memoir?

Hilu is an unofficial director of “Nathan-ism” as he suggests additional scenes, which through editing, Golod appears to do immediately like his dutiful adult child surrogate, not like an average filmmaker trying to make his own mark. Golod films Hilu’s drawings, details of Hilu’s packed Lower East Side Manhattan apartment, which includes photographs from books and his personal memories, and the surrounding environment. He also animates Hilu’s illustrations, which Hilu dubs as Nathan-ism, which is a play on the artist’s first name and -ism elevates his personal style as if it is part of a movement like impressionism. Golod also uses archival film footage to flesh out Hilu’s story.

Golod does not just focus on interviewing Hilu or staying in New York but makes it a national research tour into veteran life and Jewish history. He treks to Washington DC to interview Eli Rosenbaum, Counselor for War Crimes Accountability at the US Department of Justice, who suggests that Hilu’s drawings are consistent with photographs from that time and explains that Hilu is the only guard who discussed his first-hand experience. Golod does not have to go so far to interview Laura Kruger, Hebrew Union College Museum curator, who reveals how she discovered Hilu’s work. Kruger gives an exclusive glimpse of how Hilu’s work is being stored for posterity and her goal is to give his work more exposure though she initially considered it “amateurish.” She raises Hilu’s sense of mortality as his motivation for creating art to commit his memory to an external document, and Golod ends the film at Hilu’s grave—the artist died on April 19, 2019. Art journalist Jeannie Rosenfeld reads excerpts from her work analyzing Hilu’s art. Rosenfeld shares Kruger’s desire to give Hilu his rightful place in the art world because his work is unique but noticed the wall that Hilu erects when he feels challenged.

While Hilu was stationed at the Nuremberg trials, Golod waits until later in “Nathan-ism” to definitively verify the details of his account, which include stories about high level Nazi officials such as Hermann Goring and Albert Speer. Hilu delights in letting these Nazis know that he is Jewish, and it becomes a respectable revenge story about living well and having power over the people, including socializing with German women, who hurt people like him. Hilu credits Speer, whom he believes (erroneously) was repentant, with inspiring Hilu to tell these stories. The archival footage verifies Hilu’s accounts such as Goring’s obsession with Rembrandt. Hilu’s work is about elevating and equating his life with history, not subjective and subject to human memory fallibility; thus, why he is willing to give away his art, not use it as a stream of income, though he was employed as an artist at Bookazine for fifteen years to document Jewish life. His interactions possess a conversational veneer with his art as the conversation starter, but it is a one-way street as shown in his exchange with Rabbi Avias Bodner, who is limited to words and sounds of assent. Megan Harris, a Research Specialist at the Veterans History Project at the Library of Congress, states that Hilu submitted his work for posterity. As a folklore/memoir project. Harris equates Hilu’s art with the average veteran perseverating and telling the same story so it would not be scrutinized as like a primary historical text.

The main fact checkers are Gustavo Stecher and Lori Berdak Miller. Stecher, an art book designer, wanted to make a coffee table of Hilu’s work, but could not verify his account so lost funding. Miller, an archival researcher at St. Louis Public Library, verified Hilu’s service at Nuremberg, which was challenging because the authorized military record storage facility burned down in the seventies; however, Miller debunked one of Hilu’s prison guard tales. When Golod gently brings this information to Hilu, Hilu reacts as if Golod attacked him and starts complaining about his health, which spurs Golod to back off. Hilu recovers once Golod relents. Lest one think that Hilu is just a manipulative attention starved man, Hilu’s written account, which appears in a 1970 magazine, proves that his earlier recollection aligned with the records so he was credible, but his later artistic interpretations reflect that his memory changed and contradicted his more youthful account. In a world with Holocaust deniers, the transmogrification of memory with age does not just affect one man, but history. How do you balance allowing someone to tell their story without jeopardizing credibility and preserving humanity?

“Nathan-ism” does not have any solid answers and is essentially a post-modern film that prefers to examine the phenomenon respectfully instead of being concerned about the broader impact. Golod’s respectful positioning and acceptance of his position as the deferential child who exists to validate and listen, not challenge, is a humanist, aspirational stance, but perhaps falls short in telling a complex, nuanced story in a way that will hold up with viewers who move through life with sharp elbows and tongues. A good lawyer always leads with the negative to take the wind out of the enemy’s sails so starting with the talking heads analyzing the veracity of Hilu’s account compared to the objective facts could then segue to a section devoted exclusively to Hilu’s monologuing, obsessive drawing interactions before doing what the film fails to do.

“Nathan-ism” misses out on truly analyzing and showcasing his work. It is almost as if people value Hilu and his story more than the art, which is fair because he lived during memorable times. Jewish art is a challenging subject because as Hilu points out, he is not supposed to replicate people’s image, so it was only possible for him to memorialize Jewish cultural life and history because of his lack of formal training and inability to depict reality like a photograph, which is an amazing, unexplored parallel with the nature of his account not being accurate. These parallels are provocative and perhaps unnoticed about the nature of survival of minority groups, particularly a persecuted religious group. To survive, it cannot mimic the establishment’s aesthetics or standards because it will always be lacking in comparison.

Hilu’s work is very similar to a deconstructed comic book, and Jewish American artists are renown for being famous cartoonists. Pulitzer Prize winner Art Spiegelman is a graphic artist who addressed the Holocaust in his graphic novel, “Maus.” In addition, the use of permanent marker may remind one of graffiti art and some of Hilu’s style may remind one of Keith Haring’s more two-dimensional style. The physicality of Hilu’s people may feel like an antecedent of Robert Crumb’s way of depicting the body in an unglamorized, realistic way. If one compares photographs of a young Hilu with how he sees himself, Hilu appears more nebbish than he does when accurately depicted. Hilu’s style is anti-commercial, expresses his perception, not the reality, of his subjects and tells a story in one large frame, instead of multiple cells. Though Nathan-ism as a concept was supposed to explain how his art defied classification, it also may have been a disservice that keeps his art at arm’s length from truly entering the art world and receiving the attention it deserves.

“Nathan-ism” is not for viewers looking for a historical account of World War II and the Nuremberg trials but is about getting to know people and supporting them without requiring perfection. It also offers a lesson that Hilu and others did not learn but could have benefited from: do not be afraid of being challenged. In the end, scrutiny revealed the truth of Hilu’s experience though not every story. It does not detract from him that as he gets older, his brain, like his body, is changing. Such accountability can lead to a deeper knowing and belonging than a monologue. In the end, Hilu did tell the truth, but did not experience the true relief of being seen freely without fear. His reach can be broader in death because he is no longer rejecting analysis. Sometimes one wants too little for oneself, and by fiercely protecting that aspect of one’s identity, one can miss out on so much more. It is terrifying to think of losing one’s mind or sense of reality, but if it is accepted as a natural part of life, even death cannot win.