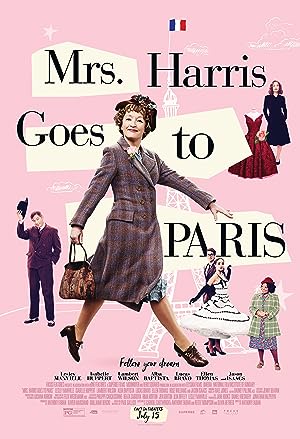

“Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris” (2022) is about the titular character, Ada Harris (Phantom Thread’s Lesley Manville), a London cleaning lady, dreams of getting a Christian Dior dress and travels to Paris to get one. What will she do if she achieves her dreams? It is the third movie adaptation of Paul Gallico’s novel, “Mrs. ‘Arris Goes to Paris,” but the first made for the big screen.

I wanted to see “Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris” for two reasons: the cast and the clothes, and though both were superb, I was still disappointed. I came to the movie with zero preconceptions, understood that I was signing up for an unrealistic fairy tale yet still was dissatisfied with the result. The film never got me to suspend my disbelief. I can buy that Mrs. Harris is the noble, selfless, salt of the earth working class who acts as a fairy godmother to anyone whom she encounters, which in turn, means good things will happen to her, Cinderella. She credits her “Eddie,” her MIA husband since WWII with the sudden change of fortune.

“Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris” sells its audience a fairy tale about class and race while reinforcing a regressive power structure through class and gender norms that often pit women against each other and encourages women to support men in leadership. Mrs. Harris is signaled as cool because she cheerfully accepts her place as one of the rare white women who shares spaces with majority of black, working-class immigrants on a bus early in the morning. She is cordial to a black bus employee, Chandler (Delroy Atkinson), and has a black best friend since WWII, Vi (Rev.’s Ellen Thomas). So the UK is suddenly a place with no xenophobia or racism. Well, maybe for Mrs. Harris so I will bite. The movie lost me when the Dior models were multiracial. In the early twenty-first century, black models were having problems finding work so while a fairy tale can be free of racism, since it is not free of all conflict, the film is making a choice about how it presents the ordinary world. It is not an aspirational image. The filmmaker is presenting the world as it is with dashes of fantasy, but the world is not effortless in its representation so it can be dangerous to act as if there is no racism.

It is puzzling that “Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris” can be a world with class conflict, but not race, however the class conflict is anemic. The numbers never add up. How can Ada survive with only three regular customers? Mr. Newcombe (Christian McKay) is framed as a jovial womanizer who has a series of “nieces,” a different younger woman every morning. Her other two customers come off less favorably: Lady Dent (Anna Chancellor), who introduces Ada to Dior, but never pays, and Pamela (Rose Williams) a struggling, oblivious, inconsiderate actress. How can she afford Ada? Why does Pamela know where Ada lives? How has Ada survived up to now with customers like these? The film clearly sees these women as low-grade villains who exploit the help. The real villain is Madame Avallon (Guilaine Londez), who is offended at Ada not respecting class boundaries and only seeing money as her right to entry. The film later reveals that her husband is the one responsible for Paris’ soiled streets and a workers’ strike, but it delights in showing Madame Avallon getting hurt from the fallout of her husband’s misdeeds. Therefore we see women as the chief ones responsible for societal ills. I want women to be accountable, but the film makes them the sole face of oppression.

One redeemable villain is Claudine Colbert, (iconic Isabelle Huppert, who must have bills to pay), as the House of Dior directress, Loulou to Dior or Bossy Boots to Ada. She acts as a gatekeeper who could shut Ada out from fulfilling her dream if not for Dior accountant, Andre Fauvel (Lucas Bravo) and Maquis Hypolite de Chassagne (Lambert Wilson). Men are depicted as benevolent and discerning judges who must check women for getting too big for their britches or permitting them entry beyond their station. Their flaws are to be pitied or are laughable, not damaging. When Dior decides to lay off workers, Ada gets the workers to strike for a hot five minutes so Dior will listen to Fauvel and save the business, but to do so, the directress must be excluded from the men’s only discussion. When she resigns in protest, Ada arrives uninvited to her house and urges her to stay. “Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris” lost me at this point. Ada advocates for weaponized incompetence, women performing all the practical labor but not having any authority or a right to make any decisions. Women do not own their labor, it is owed for the world to function even when they are not respected. I retroactively judged all the earlier moments of whimsy as deliberate ideological stances clothed in entertainment, i.e. propaganda. Bossy Boots is redeemable because at home, she is a devoted wife to a veteran.

Mrs. Harris gets checked when she oversteps her bounds by living above her station in ways that the film does not approve. When she takes a page from Pamela’s book by partying all night with the Maquis, she is late for a fitting. Monsieur Carre (Bertrand Poncet) rebukes her and the fate of the dress is in jeopardy. Then Maquis reveals his true intentions towards Mrs. Harris, and while we sympathize with Mrs. Harris, Maquis’ views are not condemned, but expected—how could we think that he could do anything else. Once chastened and returning to her station in the class hierarchy, either by working as a seamstress at Dior or terminating any socializing with the Maquis, does Mrs. Harris become worthy of our sympathy again.

Lest audiences dismiss the film’s winking at Mr. Newcombe’s profligacy, the Maquis’ extracurriculars are seen as good-natured fun, which it may be, but if a wealthy, French blue blood just likes looking and not touching, “Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris” truly is a fairy tale. To be fair, maybe I’m giving the Maquis a bad rap because of de Sade. He goes to Dior, not to shop, but to check out the models. He takes Mrs. Harris to a cabaret burlesque show. This widow may be pining over his loss, but he is also just fine.

Will the average moviegoer enjoy “Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris” if they are less analytical and cynical than I? Absolutely. It is a crowd pleaser that purveys in dreams, shows the reality that endangers those dreams then finds ways to save them and make them stronger than ever. It deserves some credit for centering the “invisible” and “nobody” though to be worthy of being seen, you must be as selfless as Jesus, which was a tall order for Jesus, who had a penchant for flipping tables and wielding a tongue as sharp as a sword. There is also the backdrop of Ada’s depression and delusion over refusing to confront her grief, which leads her friends to intervene and be concerned over her committing suicide. The dress is a symbol of how her refusal to confront her worst fears made her lose the best years of her life, and the journey to get her dress becomes a resurrection, a return to life in society.

Side note: I did not like how the opening of the film has some moments as if the characters just met each other. It only felt as if Chandler started going after Vi recently, and Vi goes from a solid no to together with him by the end. Also are we really pretending that Oscar Isaacs is an ordinary bookkeeper. Also for no reason at all than I associate them with each other, I was disappointed that this film did not find a way to pair Manville with Catherine Frot. They seem like sisters from other mothers.