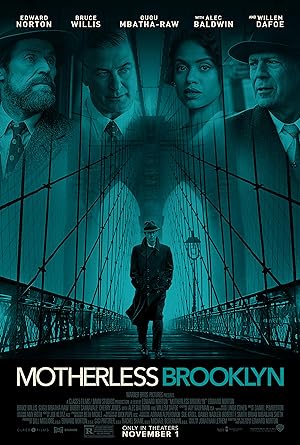

Edward Norton wrote the screenplay for, directed and starred in Motherless Brooklyn, and it could be argued that at one point, he contributed to the soundtrack, but great actors do not necessarily make great filmmakers. A passion project could just be another phrase for vanity project, but I am happy to report that Norton has come a long way since Keeping The Faith, which I think that I saw, but don’t remember. He made a solid movie that will probably improve with repeated viewings. It is entertaining if you just go to the movies for a good story, but won’t spend a lot of time reflecting on it later. It is a textured movie with a germane message without being preachy, clunky or eyeroll inducing.

Motherless Brooklyn is a story about a man who decides to find closure after a loved one’s death and what life will look like thereafter. I went in knowing nothing about the film other than the renown cast, but basically knew that it was a detective story, a film noir, a period piece. I like classic Hollywood films, but for me to enjoy one, I have to like the actors in it, and I’m not wild about modern twists on the genre. I’m not really into mysteries and occasionally lose interest in the story. Even at his most indulgent moments, I never experienced that distraction during Norton’s film. In many ways, it is several kinds of movies in one, and I liked all of them.

Motherless Brooklyn is in many ways a coming of age movie. When we are first introduced to the protagonist, he is an older man dressed like a newsie. As the movie progresses, he tries on different hats, literally and figuratively as if he was a kid trying to decide what he wants to be when he grows up. He is not a detective. He isn’t a person who works for a detective. He is a man on a journey trying to figure out what kind of man he will be: a follower, a power broker or a crusader.

Motherless Brooklyn uses the traditional film noir structure to interrogate masculine gender norms, which the protagonist never fits though he can look the part. Visually Norton favors the Edward Hopper palette when capturing New York, and while he succeeds at creating a period piece, he also finds ways to also visually subvert the way that a film noir is shot. There are occasionally a lot of cuts to punctuate a completion of movement between characters as they physically get closer, or Norton will move the camera to follow the movement of a character in the frame. There is a visual connectedness in the space, not isolation, even if we don’t know what the narrative connections between the characters are. Our minds intuit it even if we may not be conscious of it. He also injects modern visual language to interpret his character’s internal thought process. If someone used that technique in the classical era, the audience would be confused and think there was a technical difficulty whereas we take it for granted. He can also ratchet up the tension effectively at the end of the film.

Motherless Brooklyn also found a way to be about the city that does not sink the viewer into disgust, horror, apathy and helplessness. It is the anti-Chinatown without being unrealistic and saccharine. I’m from Manhattan so I instantly recognized the villain, played as only Alec Baldwin could play him, and was riveted by what appeared to be a delicious unauthorized biography of a well-known historical figure, which I did not expect and evoked The Devil in the White City vibe. The hero, if there is one, and his foil, is Gabby Horowitz. They are polar opposites, but are epic foes, and every other character occupies some part of the spectrum that falls under one of their shadows, including the protagonist. Their public battles are reflected in the quotidian effect that they have on other characters. It makes sense that there is a theme of World War II vets and existing in the city as the equivalent of being drafted into a war that you did not even know that you were waging. “I leave Guadalcanal without a scratch, and I get shot with my own gun in Queens!”

I was unaware that Norton’s Motherless Brooklyn is an adaptation of a novel set in 1990s Brooklyn and Robert Caro’s The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. Most people can’t adapt one book, and here is Norton adapting two well while changing the time period and probably more important narrative elements that I’m unaware of. If rumors that Norton is difficult to work with are true, then apparently it is because you bored him and did not give him enough to do! I’m impressed, and now I want to read Caro’s book. (No offense, Jonathan Lethem, remember, I’m not into mysteries.) Piercing, I’m looking at you.

Motherless Brooklyn is a period piece that uses the racial, socioeconomic problems of the past in the same way that horror movies use the fear of the villain as a metaphor for us to safely reflect on the problems that affect us today. In many ways, we can be judgmental about how people acted then, but if you leave the theater thinking that things have changed that much, then congratulations for recently leaving the rock. You may want to crawl back under it after getting a look around.

Motherless Brooklyn gets points for being set in New York and having black people. The protagonist has Tourette’s and is treated better in the black community than he is in his own. If you’re not a fan of its oneiric sequences, it could be because they either feel like what the character suffers from because I was left with a nagging feeling that I recognized the visual reference that Norton was paying homage to, but couldn’t quite put my finger on it, or because they do feel unnecessarily ripped off from other movies such as Jordan Peele’s Get Out’s sunken place, which is a way that he escapes from his disorder. To exist in his community, he has to go there, which is really messed up. I’m a fan of Gugu Mbatha-Raw from Belle, and she manages to escape the trope of the dame in distress. Her character, Laura, feels like a real person. Intellectually and based on their respective personal histories, it makes sense that the protagonist and Laura would connect. I loved that their relationship was clearly romantic, but on obvious levels incredibly innocent and genuine, which is a huge contrast with other characters who discuss their liaisons. It creates a gut punch when a character simply relates to the protagonist more because of his white maleness than her, whom he reduces to her sex in spite of so many other shared qualities.

If there was a flaw in Motherless Brooklyn, it is the transition between what happens at the night club when she approaches him afterwards. It feels as if something crucial is missing in the dialogue. Did she not know what happened? It is the only part that doesn’t flow. I also wondered if the protagonist was a black man with Tourette’s and the potential love interest/dame in distress was a white woman, would it be as readily accepted by audiences? Also WHAT HAPPENS TO THE ORANGE MARMALADE CAT?!?! The movie is two hours twenty-four minutes long, and you couldn’t give me an update on his cat!

Motherless Brooklyn is a great second film, and Norton should be brimming with pride. The cast is superb, and I think that it is definitely worth a trip to the theater.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.