Any description of Moolaade feels too reductive and sounds more like an afterschool special or a movie more devoted to issues than in service to the characters that inhabit the cinematic world, but you would be mistaken. It is simultaneously a very specific movie set in a particular time and an unfamiliar place that deals with an issue and practices utterly foreign to me, but is so engrossing that if you give the movie your complete attention, it is completely relatable and permits me to see the similarities in our experiences and conflicts. The story becomes universal by being so empathetic and faithful to a specific set of circumstances.

Moolaade unfolds in a village in Burkina Faso. The traveling salesman arrives, who feels like a sidequel to Sembene’s film, Camp de Thiaroye. The wives of one man are going through their daily routine. It is a normal day except a few girls run to one of the wives’ home for sanctuary. Colle is the only woman in the area that refused to let her daughter be circumcised so they correctly assume that she will protect them, which she does by using the title to create a superstitious barrier at the threshold of her house symbolized by a colorful piece of rope. Animals, toddlers and people easily scale this barrier, but it immediately creates a controversy that ends up being a battle of wills between Colle and Doyenne des Exciseuses, the women in charge of circumcisions, who then stirs up the men of the village against Colle. It mutates into a battle of male domination over women. Shouldn’t a man have absolute authority over his wife? This battle mutates into religion and tradition versus modernity, and men unwilling to toe the line face disproportionate backlash than even I expected. A formerly individual choice and act becomes polemic and a statement on the collective, which causes people to pick sides—people who were willing to compromise, tolerate and/or maintain the status quo. The entire village is plunged into conflict, and even the denouement of the film suggests that the conflict lines are sharper and more resolute, but ultimately unresolved and will spill over into other aspects of society. On one hand, it is hopeful because people are ready to be vocal and take sides. On the other hand, those who prefer the status quo, who would not have been personally affected if they had minded their business instead of imposing their will on others, have dug their heels in and are willing to resort to violence.

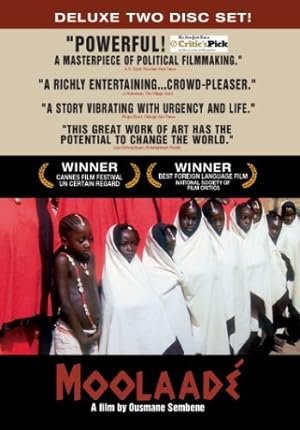

Most people describe Moolaade as a movie against female circumcision, which seems too reductive considering that it is inhabited by vibrant characters, specifically a host of black women. These women are permitted to represent the complete spectrum of humanity and don’t have to be beacons of progressive thought and perfection, but sometimes are brave, other times are as repressive as the fifty-two percenters while others are only interested in their own circumstances. Because this village is completely black, and while there are outside influences, because they are not depicted on screen, it subtracts the dynamic that we are usually used to, an expectation of perfection, and just makes them women, human beings. It also negates the need for solidarity of black people at the expense of black women. Remember that the director, Ousmane Sembene, is an African black man, the father of African cinema, whose first film was Black Girl and his last was Moolaade. His films have always expressed a concern that regardless of whether or not Europeans or Africans, Christians or Muslims dominate society, black women are the foundation, but are treated the worst. By focusing on the struggle of black women is like focusing on the canary in the coal mine—everyone will be negatively effected, but some get hurt first.

Moolaade is far more germane to our society than we may be willing to admit. It is how those who wield power and represent the status quo feel threatened when an individual’s choice differs from theirs. It isn’t enough that most people agree with them in deed and are complying. In this case, it is only four little girls and a woman, complete nobodies and the minority in this village, that disagree with the status quo, but they are not calling for solidarity or discouraging others from the practice. Colle actually fears that people will misinterpret her actions in this way. The disproportionate backlash to individual choice actually creates a boomerang effect and undermines the status quo more than any individual choice. When the individual refuses to back down and the backlash affects more people than the original dissenters, then it leaves them two choices: join in the backlash, which ultimately isn’t possible in the long term if the punishment hurts some aspect of your life that you cared more about than the original issue, or join the individual. It amplifies the power of the dissenters by increasing the numbers and moving the goalpost of approved and disapproved behavior.

When people talk about radicalized behavior, it usually starts with the reactionary, not the dissenter, who becomes radicalized in the face of dissent. Most people just want to be left alone to live life as he or she sees fit, not to become a spokesperson on some issue. Moolaade shows that the reactionaries accuse the dissenters, a woman and a handful of little girls, of doing what the status quo is actually doing—undermining the husband’s power, the man’s power. Colle’s husband was a happy man until other men told him that he was not. A group of men literally are telling another man what he should be doing in his home, whom he should be marrying and how he should act at home. It punctures the illusion that a man is the supreme ruler in his own home if other men can undermine that man’s original way of living, which shows that all of it was fiction. A man was never the head of his home since there is an authority over that man. They’re basically getting into bed with him and affecting him at the most intimate level.

Sembene takes it visually one step further. If you side with the reactionaries, you look like a rapist or worst, a pedophile. Initially one man pushes back on that characterization, but later has to concede. Moolaade uses mounds as cautionary tales of violating the protection-an anthill symbolizes a man transformed like Lot’s wife. That anthill bears a striking similarity to the local mosque and later a different mound that dominates the final frame. Even though Sembene does not explicitly equate the three, it is a strong condemnation of religion in society.

If I had one criticism of Sembene, it is his confidence that exposure to Western culture will automatically result in a rejection of the worst aspects of traditional village life. To be fair, his other movies do not always share that confidence, but it seems to be a prevailing sentiment because he was that person-a person who chose and embraced certain aspects of Western culture while adhering to and rejecting aspects of his birth; however as someone completely immersed in Western culture, I am sad to reveal that the most reactive elements of village life is actually universal though it may appear differently depending on the context. Moolaade is the final masterpiece of the father of African cinema.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.