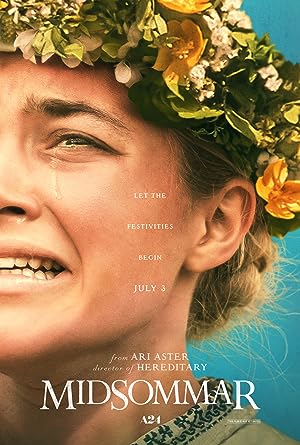

Midsommar is Ari Aster’s second feature length movie after Hereditary, and in this movie, he wreaks havoc on his characters before the opening credits even roll. Lady Macbeth’s Florence Pugh stars as Dani, a psychology student who experiences great personal tragedy, repeatedly chooses the absolute worst set of people to lean on, but still finds a certain type of happiness when she goes to Sweden to attend a nine day midsummer celebration, which we only see a few days of ceremonies (what happens AFTER the movie)! If you liked Hereditary, then you’ll enjoy Midsommar, but whereas Hereditary may have left you feeling utterly bereft, Midsommar can at least be seen as a happy ending for some of the characters.

If you never saw Hereditary, but are curious about Midsommar, imagine if Wicker Man, Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria, Gasper Noe’s Climax met Hannibal, the TV series, with a European medieval aesthetic, but we mostly got to experience how the cult sees themselves instead of purely seeing them as the villains. The whole story is still bananas, but if that kind of movie appeals to you, then you’ll want to see this movie immediately. Even though the movie is almost 2.5 hours long, it really flies by. I’ve heard people compare it to Mother!, a movie that I despised and regretted even seeing once, and if you don’t like the aforementioned movies, I can see detractors not being able to differentiate between the types of madness and chaos depicted in these films and Mother, but in terms of story, it is light years ahead. I think that the simultaneously closest and most distant soul brother to Aster is Lars von Trier, but I would brunch with Aster because I think that he is using film as therapy to work through real pain whereas I would avoid von Trier because he seems to get titillated from the pain and extremeness and seems content in wallowing in a self condemning, doomed place. I am alarmed by rumors that he wants to explore genres other than horror.

I’ve actually seen Midsommar three times. The first time was during its opening week, and I did not intend to, but I watched it completely as a viewer, unable to take notes lest I miss a single frame on screen. I was completely absorbed, eating real butter popcorn and into the movie even as I took mental notes because of my familiarity with Aster’s trademarks: abrupt cuts, head trauma, deformities in children with artistic ability, weird light focus, random symbols, distinct auditory association with the weirdness. An eagle-eyed viewer will be able to figure out everything that is going to happen if you’re paying attention to every detail in each frame. You may not believe what you’re seeing, but Aster has proven his willingness to go there, and he never flinches so don’t doubt your reading of the imagery. It is going to happen. After the movie, I enthusiastically dove into the rabbit hole to get others’ perspective of the movie because I hate being repetitive so if I’m not writing about it here, I probably noticed it, but it was written elsewhere.

I waited over a week to watch Midsommar two more times in the theater so I could really dissect what I liked about this film. The second time was completely devoted to note taking and observation, and the third time was a hybrid of my first and second viewing experience. In many ways, my viewing experience mimicked the experience of some of the characters on the screen. I think that on some level, Aster’s films are also cautionary tales for viewers not to get too absorbed or swept away by the spectacle even as we get swept away by the spectacle. Aster is really masterful at making sure that the viewer never feels superior to the main character even as we may mentally chide them for doing things that the viewer wouldn’t do because like the main character, we get absorbed in the setting regardless of how personally abhorrent we find it. We can’t admonish them for not walking away if we don’t.

Unlike Hereditary, I actually think that Midsommar loses a little oomph with repeat viewings in the theater without the benefit of closed captioning and/or translation of all the dialogue, which is deliberate, or the ability to freeze frame, rewind or zoom into an image if you already know the story, but then you get the benefit of noticing the audience’s reaction and how we as the viewers are just as manipulated as Dani and can compare and contrast the similar and dissimilar reactions of different audiences. I am eager to watch Midsommar at home if there is commentary to explain every image on screen. Literally everything on screen means something even if we don’t know it or can’t find it through research, but like the cult community, this film does not privilege knowledge over emotion. We are supposed to understand it on a visceral level.

Whereas Hereditary could support two readings, a supernatural and a scientific one, for a movie with a ton of rituals, the supernatural is mostly absent in Midsommar, which makes it more terrifying to me. Everything that happens is because human beings wanted it to happen though some may provide a spiritual veneer for their selfishness and dehumanization of others. The techniques of using people vary depending on culture and location, but it becomes so extreme that it is impossible to rationalize on a sane, rational level by the end of the film. Even though Aster has explicitly denied any connection between Hereditary and Midsommar (other than himself of course), I think of Midsommar as a spiritual prequel to Hereditary to explain how we got such a screwed up matriarch whom we never actually meet in the film.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

I love Aster for confronting people’s definition of family and not allowing it to just stand as a warm, fuzzy, good or positive aspect of life. He depicts three kinds of families in Midsommar: the inadequate biological family that Dani must distance herself from if she wants the potential to have a normal life, especially since she is not the focus of it as the comparatively healthy daughter; the chosen family as Mark characterizes them of friends brought together by a relationship, Dani and Christian, or anthropology studies, Mark, Pelle and Josh, but without any genuine enjoyment in the individuals of the group, but only for what they can provide each other; and Pelle’s “family,” which is a hybrid of both-you can be born into it or be adopted by it, but it is ultimately unhealthy, cannot be sustained without constant self-medicating, obliteration of the individual and dehumanization of anyone that doesn’t belong. Normally I would dissuade anyone from taking advice from How to Get Away with Murder, but every character in Midsommar needs to live by this quote, “It’s called adulthood. Everyone of us is alone all the time.” Each of these characters’ unwillingness to be alone or a whole individual who can stand alone without depending on another’s approval or conditions is the horror that underscores Midsommar.

Did Pelle and/or his “family” play a role in Dani’s family’s demise? Based on the opening scene, a linen quadriptych depicts the entire movie in four acts then parts in the middle like a theater curtain opening on a show, I would say yes, it was premeditated. Also the color scheme of Dani’s childhood home is yellow and blue, and the floral pattern of this home and her apartment suggests an aesthetic link to Sweden. Pelle classifies his family rituals as theater. It is possible on some innate level, but not explicitly logistically linked. Pelle can’t predict how people will react even if he was responsible for her family’s murder suicide in some way. He could only set the stage.

Midsommar has an explicitly backwards, regressive trajectory. Given Dani’s Swedish aesthetic before the trip, it could be theorized that maybe her family originated in Sweden then immigrated to the US. (If you know where her family home suburb is located or where she and the guys go to school, please let me know. I don’t think that the movie mentions it.) Dani’s journey is a kind of self-deportation, not just back to Europe, but back to a Europe that predates our cultural time. She has all this technology, but no authentic connection, so on some level, it makes sense to yearn for a past when everyone that could love you is in reach. When the characters discuss Sweden generally or the Hårga, the community Pelle is from, specifically, they ask how they get their women or keep up their genetic diversity, and this movie shows us how that happens. It attracts them to the concept of a simpler time, a rose-colored view of the past that did not exist which her ancestors probably fled from screaming.

No matter how much we empathize with Dani’s tragic journey to oblivion and enjoy Christian, her boyfriend, finally getting called out on his crap in the most extreme way possible, Midsommar’s depiction of this catharsis should not be conflated with something that is good. For me, the most terrifying moment in this movie is when Dani has a choice on whom she should lean on for support, a woman friend whom we never see, but is obviously genuine, healthy and understands Dani on a deeper level, or Christian, whom she should not have been dating, Dani chooses Christian, whom she knows is completely incapable of providing her with what she needs and worst, is always objectively and morally wrong. On some creepy level, Dani knows that she has overtly trapped Christian into staying in a relationship with her because to do otherwise would make him seem like a bad guy.

Dani is the fifty-two percent, which I did not originally mean in a political way, but as a socioeconomic example of how that demographic lives her daily life; however the filmmakers explicitly meant the story to be taken in a political way because apparently Sweden is also going through a return to fascism so they used the colors of the flag, blue and yellow, to depict horrific moments. Dani leans towards fascist values in her personal choices. Dani’s unspoken promise to Christian is to make him feel like a good guy when he isn’t if he continues to go through the motions of a real relationship. On some weird subconscious level, Dani defines her value on her relationship with a man, regardless of the quality of that man, and she will use the currency of her dead family and authentic trauma to keep him instead of actually tackling that real pain or fully exploring her chosen profession. It isn’t like she doesn’t know better. She is a psychology grad student.

As much as I may prefer and empathize with Dani over Christian, they’re both trash individuals, but because we have her backstory, I kept making excuses for her. Instead of just breaking up and going into the unknown with the possibility of happiness, they both lack the courage to call each other out and say that the other isn’t what he or she wants. Instead they’ve trapped each other in this relationship filled with passive aggressiveness, lies and obligation. They’re two sides of the same coin. We hate Christian for being a cheater in heart and deed, but Dani is completely open to sliding over to Pelle though she is concerned with appearances. They both would rather engage in their little trite relationship issues than develop as individuals or professionals. They both leech onto other people’s lives without any independent passion. They are both emotional manipulators of the people around them that they claim to care about and impose themselves on others, but it is more socially acceptable for Christian to do it. They don’t really love other people for who they are, just how those other people make them feel or how useful they are. They’re not capable of real love. They’re mentally children in the bodies of adults. We only see them take, not give.

Before Midsommar even goes to Sweden, I was experiencing the vicarious social embarrassment of the guys’ reluctant social charity. I would rather be alone than for someone to hang out with me who doesn’t really want to, but either Dani is oblivious or chooses to ignore that she isn’t part of the group. Never forget that she has at least one real friend who loves her and wants better for her than she wants for herself, but she chooses this group. During the first onscreen conflict with Christian, she literally begs Christian to move to the space where he comforted her after she discovers her family is dead. She wants to be there forever, constantly soothed and comforted, the focus of his attention, even if it is a place born from sorrow and gut wrenching pain. Maybe she is making up for the attention that she didn’t have because her parents had to focus on her sister more, but that doesn’t mean it is healthy. Why would you choose to feel alone in a crowd?

On the flip side, the first shot of Christian is perfectly composed. He is at the center of the table underneath a photograph cropped to only show the subject’s boobs above his head, which may as well be a thought bubble because he is incapable of dealing with a real woman, just woman parts. Mark is at the right side of the screen, and Pelle and Josh are sitting at the other side of the table. There is an innate imbalance from the beginning. Christian has no physical allegiance to his friends—he is literally not on anyone’s side except his own. I did not catch it the first time, but Josh, the earnest anthropology student who is black, completely gets Christian. Christian keeps busy so he doesn’t have to confront himself, a white sepulchre, a shining paragon of mediocrity disproportionately rewarded as an accidental congruence of biology and opportunity rooted in time and place. (So how did Josh and Christian become friends?) Christian is an expert manipulator in playing people off each other so they don’t recognize him as the bad guy, specifically Mark and Dani; however Christian is an amateur in comparison to Pelle.

Pelle is probably the most disturbing character in Midsommar because he acts like he cares, but he knows that everyone that he is inviting to his home is potentially going to die. He seems like the perfect guy, but he is like the mother in Get Out in the way that he deliberately triggers characters’ trauma and vulnerability to divide and manipulate them; however I can’t completely hate him because he is also a victim, an adult who never recognized that he was suckled at the teat of abuse and never escaped even when he left. He has never reflected on whether the life that he lives is a healthy one. I thought that the scene that explained him perfectly is when he tries to calm Dani down, tells his origin story and uses the Socratic method to tell her that Christian is a dreadful boyfriend. During this moment, he offers a substance to Dani to smell, which he uses first and desperately. Pelle is a good actor so maybe he was just pretending to need it to get Dani to use it, but everyone in the Hårga is incessantly drugged out of their minds to function as a unit. We never explicitly see Pelle do anything evil, but one minute he is gardening then we see a black leg sticking out of the ground days later. Strange fruit. There is no privacy, no individuality, no independent agency without consent of the collective, no dissent, no claim over anything as truly yours. Pelle never lays the blame for his trauma on the community that caused it, but credits them for making him not feel lost after the trauma. “Everyone does everything together.” That isn’t normal, honey.

Hårga is an interesting community, which I call a cult for their secrecy and this aggressive refusal of its individual members to evolve or interrogate their way of life. Their idea of home is warped. They go into the world, but are unchanged by it. They only go out to lure victims or recruit. They believe that their survival is dependent on mostly involuntary human and animal sacrifice. They lie or remain purposely vague to get what they want from members or outsiders: you’ll feel no pain or fear; you won’t have a bad trip; free sex; we dated or were friends. They thrive on feeding your paranoia or pushing your body to extremes then offer themselves as the solution to the problems that they exacerbated. When Pelle asks Dani if Christian feels like home, Aster immediately cuts to what Pelle calls home: smashed faces and burning bodies. Christian is definitely not home, but Hårga is not home either. As Simon would scream, it is fucked.

The entire community is based on a weird rhythm of division and embrace, assault (administering drugs or substances without consent), pushing people to physical and psychological limits (the midnight sun leads to natural sleep deprivation), making people feel accepted, loved and welcomed then abruptly withdrawing that love. The obvious external signs are replacement of relationships, change in dress and diet, chanting, games, isolation. The process only takes a few days as depicted in the film, which can then lead to loss of self. Instead of owning up to their flaws, they project them on to others and literally create scapegoats (or scapebears) to punish instead of doing better or reforming their community. Their blessings are repulsive-a bountiful table is filled with meat touched by flies. If you look closer at this community, you can almost hear the banjo.

Midsommar takes our cultural associations and flips them on our heads. We associate white, sunlight and brightness with safety, joy and goodness, not Lucifer. We’re socialized when traveling to politely participate and mimic what others are doing in ceremonies instead of asking whether or not we should want to be a part of that ceremony and whether the meaning of that ceremony is aligned with our values before participating in it. Instead of enjoying the process of becoming something bigger than yourself, you should be asking if it is worthy of you. I probably could have been tricked into going to Sweden and thought all those villagers were harmless because they are overtly friendly, but they would have lost me with the drugs. Would I have gotten killed early or been permitted to turn around since I didn’t actually see the community? Probably killed. It will be interesting to see how this film affects Swedish tourism.

The most realistic parts of Midsommar are how quickly the characters of color disappear because two of the three characters of color are the quickest to call the Hårga and their friend, Ingemar, on their crap and see them for what they really are, cruel. Simon and Connie refuse to go along with Ingemar’s story, but are not initially alarmed when he agreeably and abruptly changes it, also known as lying-something that Christian and every member of the cult frequently do depending on the information that they are confronted with. When Simon and Connie witness the senicide, it is the line that they refuse to accept spin on. There are less extreme ways to end your life if you choose to do so. This “family” is rooted in eugenics (hi, Nazis) disguised in religion and harmony with nature. When you’re old and a burden, you die to not be a burden and make room for additional members—the baby and Dani. Arguably the old man and women are the first two victims even if they volunteer. When you’re young, you have babies with whomever the elders approve, even if that person is a stranger, a fool or a close relative. People’s values and roles are reduced to their biology. Years of indoctrination have groomed this community not to interrogate, challenge and change their community’s values so it is not a surprise that the outsiders who do are the first to experience the abrupt withdrawal of hospitality. Ingemar’s invitation to the first two characters of color is possibly rooted in jealousy for not getting the girl and a way to get revenge even though he appears friendly. He knows what will happen to them, and their vocal disapproval only sped up the process. Dani expresses concern at their disappearance, but sees them as a foil—her relationship doesn’t measure up to theirs.

Josh isn’t like anyone else in Midsommar. He is the true anthropologist divorced from emotion while observing the community and apart, which is amazing because usually our image of an anthropologist is a white man studying a primitive culture whereas he is a black man studying a primitive culture. Primitive is usually associated with communities of color, but Aster has explicitly associated primitive with white communities who engage in religious practices. There is resistance to Josh’s existence. To Christian, he is a sudden unwanted rival because of ability and merit, which is rich since he only decided to study something yesterday. Josh’s intellectual curiosity makes him a danger to the community and their values because he is not emotionally vulnerable or open. They only see him as a human sacrifice regardless of how genuinely accepting and uncritical he is of their culture, and his intellectual curiosity makes him the proverbial cat. Before he dies, he is staring at a page in his notebook, and it looks like he genuinely figured something concrete out about the community. If you know what that page says, please let me know. I’m talking about the scene before he abruptly moves from the table to his bed right before he sneaks out at night. In the end, he forgets that anthropologists often die in the field at the hands of those that they are studying. Intellectual distance should not be equated with a force field of protection. Anthropology has explicitly had to tackle how women’s work is restricted by gender and concerns of safety, but Midsommar implicitly broaches that race could restrict it as well both within academia and in the field.

Mark is the first victim who is not a character of color. He is Christian without the intelligence to try and appear like a good guy. He is also what he thinks Dani is, completely needy and out of place. He is the stereotype of the ugly American tourist, culturally insensitive, reductive and objectifying in the crassest way possible regardless of context. He breaks an unspoken rule, but worst, doesn’t understand why he was wrong after Pelle explains how he violated that rule. After he died, he literally reminded me of Michael Myers’ mask. Shudder. He is also the only character who unwittingly pegged the community perfectly. He called it Waco.

When Dani compliments an older member of the Hårga for his outfit, he cites the hermaprodite qualities of their community, which suggest that the rituals have a yin and yang kind of complementary pairing that requires a woman and a man. Superficially it appears that Dani is rewarded, the only outsider to survive, and Christian is the final victim because he dies a brutal death, but Dani dies as an autonomous individual with a moral core and happily embraces oblivion by accepting the values of the cult. She finds out the twist in The Stepford Wives or Get Out, but instead of fleeing in terror, she enthusiastically signs up.

Dani and Christian’s reactions to witnessing traumatic events is interesting. Dani notices the disappearances and is appalled that Christian doesn’t. She knows that something is up between him and Josh, but unlike a normal person, never asks either of them what is going on. The drug use and senicide trigger memories that she can’t possibly have of her family’s death (she wasn’t there-only we saw it unless she saw crime scene photos). Christian only sees the senicide as something cool and flashy for his career and instead of comforting her, he rushes through a trite rationalization for leaving her (“take some time for yourself”), runs to Pelle for permission then Josh to metaphorically kick him in the balls. Unlike Connie and Simon, the trauma drives a wedge between the couple. Connie and Simon try to stop the rituals. Dani and Christian continue to participate. Dani’s continued participation is especially puzzling considering how much it disturbs her, but is explained when you realize that for staying, she gets rewarded with attention from Pelle, then the Hårga women who call her beautiful and finally the entire community that crown her their May Queen. [What happens to the May Queen after that day?] She is being love bombed. She is more appalled that Christian does not care what she is saying than the substance of what she is actually saying otherwise the “family” would repel her. Like any good fifty-two percenter, she has centered herself in others’ tragedies. It is really all about her. I particularly found it odd that now among strangers, she found comfort with a group of women and embracing traditional gender roles, which she rejected when it was genuine, beneficial and carried the potential as a catalyst for personal development. Hårga rewards her, but unlike the average final girl, she does not defeat evil, she becomes it by accepting the embrace of this “family.” It is horrifying how happily Dani embraces her destruction. Throughout Midsommar, her auditory POV is depicted as dissociative, checked out, but tuned in when something emotionally threatens to throw her off balance, but during the dance, she is in a completely heightened sensitive state that amplifies the sound of the music whereas Christian hears in it in a less resonant way.

Christian initially seems to be rewarded for being a jerk. Maja is interested in him (how old is she), and everyone in the Hårga encourages it. He gets permission to write about the community and is treated like Josh’s intellectual equal, while setting himself up to benefit from Josh’s work by calling it collaboration while offering nothing in return. Even though he clearly is sexually interested in Maya, because he was drugged, I kept asking if he was actually raped. It takes place in the same spot where Josh was killed, the place where all the sacred texts of the oracles are kept. Afterwards he runs off in terror recognizing that he is alone, and the Hårga show that they’re fans of Wes Craven’s The Serpent and The Rainbow because they rob Christian of the two things that make him a person: his ability to move and speak. He becomes what he is substantively: nothing. He is helpless in a chair, but Dani seems just as helpless, smothered in a pyramid shaped gown and crown of flowers. I don’t recall either of them speaking during the end of Midsommar after her discovery and after he feels sick at the table.

Do the Hårga manipulate Dani into discovering Christian’s infidelity? It does not matter since they are complicit in it. What kind of family encourages a sister to cheat with another sister’s man? A family that wants the sister angry at the man by making him the focus. They were going to kill Christian anyway, and Dani made a choice even if she was psychologically manipulated and drugged to do it, but now she and the cult are forever bonded by this choice. Dani never gets angry into being manipulated into taking drugs without her consent. Does she ever get her blessing from Siv or was it a one-time offer? Will she get punished for deviating from their tradition later? We don’t know, but I wouldn’t be surprised. When she spits out the herring, they treat her like a stubborn baby, amused by her antics, but to be fair, in their eyes, she is less than a day old since she only became a member of their “family” during the dance. Dani continues to regress by discarding her crown when she gets upset and being soothed by a group of women like a baby. The Hårga take “mourn with those who mourn” (Romans 12:15) to all new empathetic lengths. Only one thing is certain: Dani is genuinely happy at the end because she is the center of attention and special. She isn’t the May Queen. She is the Mad Queen. At this point, she knows what happened to Connie and Simon, Mark and Josh, and what will happen to two men who are alive. She has seen them wheeled in with Christian, whom she has sentenced to a fiery death for infidelity. Dani doesn’t care because, as one of her new sisters cheers, “You are the family now.”She doesn’t seek to punish the community for encouraging his betrayal. Side note: Is it just me or isn’t it interesting that in 2019, we have two Danis who reach their climax as a character by giving in to her worst impulses and chose burning? Midsommar wore it better.

When Midsommar ended, I was left with so many questions. I’m assuming that Pelle never returns to the US because eventually he would be questioned about the disappearance of at least three students although given his affable demeanor, anyone would believe his story. Assuming that Dani is still a member of the “family” and survives the ritual, she would never want to leave the Hårga, or she would start suffering from withdrawal of drugs and love bombing. Also she would have to face what she had done, and it would not be as easy to rationalize her actions in the outside world. Mark doesn’t seem to have close family ties so maybe no one will be concerned that he did not return to school, but what about Josh and Christian’s families?

Earlier I noted that the supernatural was mostly absent in Midsommar, but not entirely. There is talk of “The Source,” “unclouded intuition,” and “The Influence.” We maybe see its effect when Dani suddenly speaks Swedish. On the other hand, she is high and can’t be trusted objectively. I only speak English; however without being high, as a child, I have actually had moments when I was unaware that someone was speaking to me in a different language until I responded correctly in English to their inquiries and the person caught themselves and realized that they had slipped into their birth tongue by accident then asked how I understood what he or she said. Shrug. I don’t necessarily chalk it up to the supernatural just something inexplicable. It does remind me of the Tower of Babel. Dani does seem to have some precognitive connection with her biological family (she knows her sister’s email is different) and the “family.” She seems to anticipate what will happen before the elderly man and woman commit senicide. She has a vaguely prophetic dream during her third night there. None of these moments are inherently supernatural. If you’ve been taking drugs and traumatized, your brain may process things in an unusual manner.

There were certain images that struck me after repeat viewings: the red tops of the spaghetti masks reminded me of the MAGA hats mashed together with KKK hoods hiding the identity of the torch bearers; the torches in the yellow temple reminded me of Nazi rallies. The Nazis were really into the occult while happy to cloak themselves in Christian drag, which some Christians happily cosigned and betrayed the teachings of Christ because it benefitted them in this world-their identity, their ego, their inadequacies, but ultimately Christian, who betrays his name, his friends and his girlfriend, is ultimately betrayed by lying down with the very forces that will destroy him. He is THE fool.

Ultimately the lesson of Midsommar is NOT to be like Dani and Christian. Don’t make a deal with the devil because you’re the only one who will get burned in the deal. Learn to be alone so you won’t accept anything as a community. Withdraw from community that thinks you’re too much. Be honest in your relationships and recognize what you can and can’t offer another person in terms of support. Be comfortable with the full complete emotional spectrum in others and yourself. Imagine yourself as the villain and reverse engineer and avoid those steps if possible.