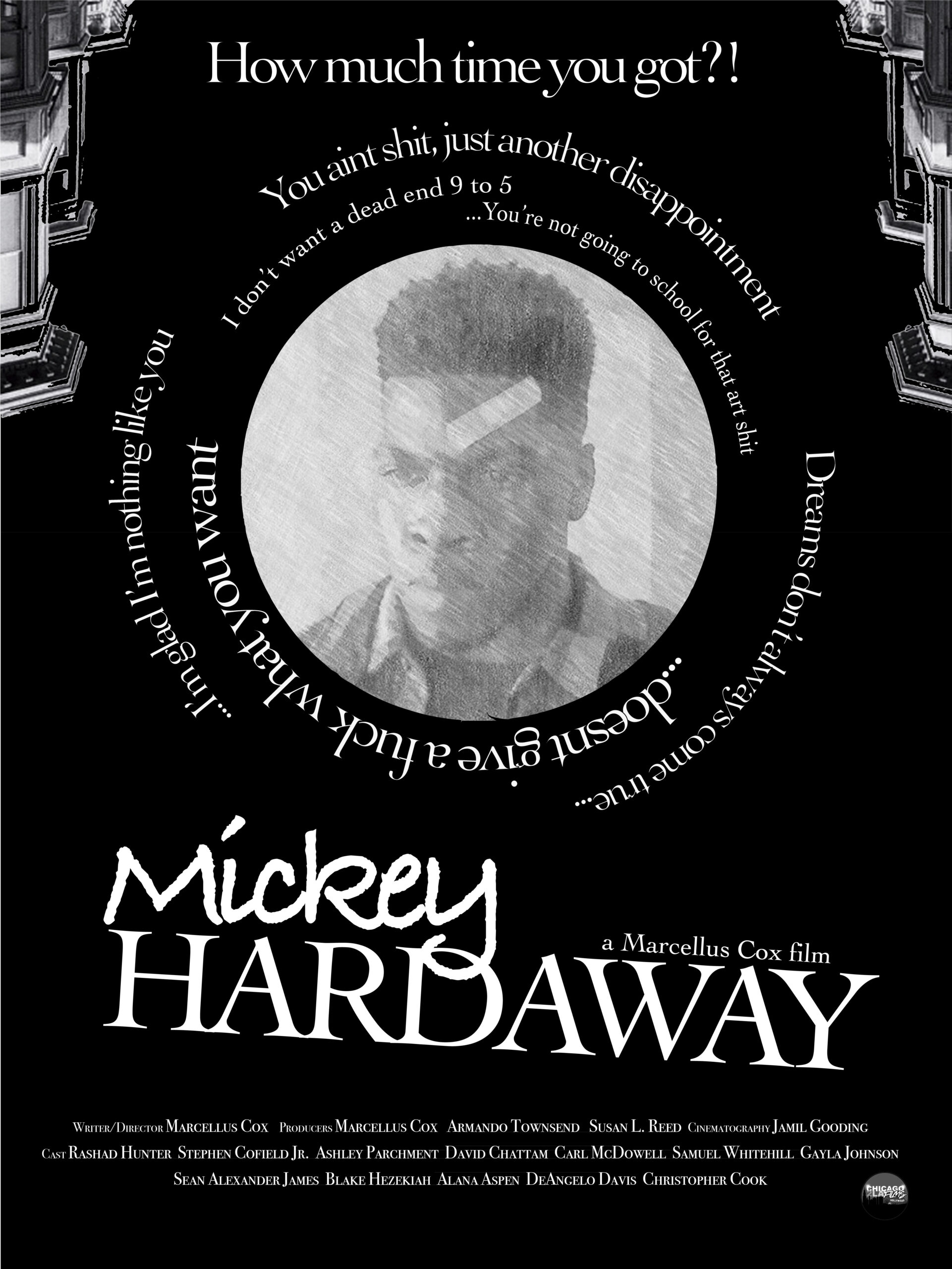

“Mickey Hardaway” (2023) is the feature directorial and writing debut for Marcellus Cox, who expands his 2020 moving nineteen-minute short. Cox’s first film feels like a contemporary reprise of Richard Wright’s “Native Son” without the misogyny or Thomas Hardy’s “Tess of the D’Urbervilles” if Tess was a promising young Black male artist in twenty-first century Los Angeles. The titular character (Rashad Hunter) is a sketch artist who decides to seek therapy from Dr. Cameron Harden (Stephen Cofield Jr.). During these sessions, flashbacks reveal the various events that contributed to how he wound up on the couch. Will he overcome or surrender to his trauma?

Even when armed with talent, an artist from a working-class background faces an uphill battle without the resources to provide security against failure, but Mickey’s father, Randall (David Chattam), makes it harder with frequent beatings and deliberate sabotage. To counter his father’s abuse, Mickey’s teacher, Joseph Sweeney (Dennis L.A. White), and guidance counselor, Mt. Pitt (Charlz Williams), try to encourage Mickey to pursue his dreams. With student loans weighing him down and without family support, Mickey is on the brink of despair until he gets a job with Nathan Hammerson (Samuel Whitehill) to publish his comics in his region’s newspaper and finds true love with his rec center art student, Grace Livingston (Ashley Parchment). Even with these bright spots, Mickey finds himself repeating some of his father’s mistakes. As Mickey faces new obstacles, he seeks therapy at Grace’s urging with Dr. Harden, who relates to Mickey’s struggles, but also establishes some firm boundaries, which Mickey resents.

“Mickey Hardaway” is not a story told in chronological order. It starts in medias res with a scene that occurs later in the film then rewinds to Mickey confiding in Grace that he has reached a tipping point. Unfortunately, that means that from the beginning, the audience already knows which side of the scale will be heavier. The movie consists of three therapy sessions, which leads to flashbacks chronicling each blow on Mickey’s psyche. The buildup to introducing Randall works as people talk about him ominously, and when he finally appears, Chattam’s performance ensures that Randall lives up to his fearsome reputation without erasing his humanity. Cox consistently balances humanizing and sympathizing with monsters without excusing them—a rare gift. Randall is punishing his family because he feels as if they held him back from pursuing his dreams.

Scenes set in the present felt as if they did not carry as much weight as the past, especially the dynamic between therapist and patient, which felt underdeveloped and more like a narrative device. When Mickey keeps trying to get Dr. Harden to relax his rules and prove that he cares, it helps to explain Mickey’s later grievance with him, but does not pack the same punch as the flashbacks. It could be the point that Mickey no longer needs a specific grievance to develop resentment, but then his rage would not be limited to a therapist or mostly men; however the short seemed to signal that the therapist patient dynamic was going to be the central focus as a redemptive, alternative relationship that would act as a fraternal like bond to reassure Mickey that his relationship with his father and his career would not always feel like such a dead end.

Even those viewers who enjoy a bleak film will find “Mickey Hardaway” challenging. The plot is realistic to a point as the friendless Mickey faces bullying, physical child abuse, career exploitation, and poverty, but the story also neglects some natural consequences. For example, there is a shocking scene where a physical battery in the first act is met with no reprisals. There is no ineffectual Department of Children and Family investigation even though the teachers know that Randall is a menace to his family. The cops only appear when Mickey does wrong as an adult. If realism would favor Mickey it is omitted, but if it further tortures him, the pile on will continue. The older brother, Travis (Christopher M. Cook), evaporates after one scene and is curiously missing for the rest of the film, but he seemed to be Mickey’s first champion. Initially it felt as if Mickey’s mom, Jackie (Gayla Johnson), was going to be a verbal abuser and undermine young Mickey’s self-worth, but Cox makes her an ineffectual, passive presence who encourages his talent without protecting him. She is a woman character who feels flawed and more three dimensional than the other women characters. The initial interaction between Mickey and his boss is a battle of wills, but when Nathan finally convinces Mickey to work for him, the dialogue needed more revisions to reflect the exact persuasive moment and phrase that was convincingly different from earlier.

“Mickey Hardaway” is dialogue heavy, which raises the same question that moviegoers may have when watching a film like “Daddio” (2024): could this movie be a play or is something about it cinematic? It could easily be a reprise to August Wilson’s “Fences” with the son taking the spotlight. There is nothing wrong with a play being adapted for the big screen so more people can be exposed to the work since the theater can be cost prohibitive and inaccessible to most, but this movie is not like that. Cox uses black and white film for most of the movie but shoots in color when Mickey finally feels joy. It is a brief interlude that could have been used more when Mickey was sketching and mentally was transported out of his discouraging surroundings, but then would run the risk of feeling gimmicky. Also, the black and white is crisp and clear, not muddy and with loss of quality in images, which is a rookie mistake that Cox avoided and is harder than it seems if one looks at early black and white experimental films with less definition. Also he has the advantage over “Game of Thrones” for making his film’s nighttime scenes crystal clear, and the film looks the same regardless of the size of the screen. The visual quality does not diminish proportionate to scale.

If “Mickey Hardaway” has a fatal flaw, it is the inadvertent dissonance of a movie, the ultimate, risky and glorious creative act, telling a story where Mickey’s actions validate his father’s fearful judgment about the life of an artist. While the intent may be to sympathize with Mickey and boldly tell a story about the practical problems that artists without resources face, it feels more like a Sid Davis cautionary film warning children about the dangers of art and how it will lead to nothing but heartbreak and disaster. Upon repeat viewings, it is the people who encourage Mickey who deliver him to this fate, and his father’s discontented grumblings sound prophetic. For instance, Mr. Tate informs Mickey of some seemingly good news, which motivates Mickey to finally stand up to his father and strike out on his own. Mr. Sweeney introduces Mickey to his sinister boss. Therapy ends up being another place where Mickey feels thwarted and may have exacerbated the situation. There does not have to be a happy ending, especially since the world is filled with people like Florence Ballard, a former member of The Supremes whose label kicked her to the curb despite her acclaimed voice, but the denouement seems excessive with an ambivalent tone. If Mickey’s actions are justified, there should be a smidge of catharsis regardless of disapproval. Instead, it feels like a tragedy.

If given the choice between “The Photograph” (2020) and “Mickey Hardaway,” which is like comparing apples with oranges since both films will appeal to different segments of society and have contrasting objectives, but share an intersection of romance between two Black fellow artists, the latter feels more rigorous and organic in its willingness to acknowledge that being an artist and finding love are not only glamorous and swanky, but are often the byproduct of pain and trauma, which sow the tares beside the wheat. America may have found its version of Lars von Trier in Cox, but hopefully he is not plagued with as many inner demons as the Danish filmmaker or his protagonist.