“Wherever you go, there you are.”

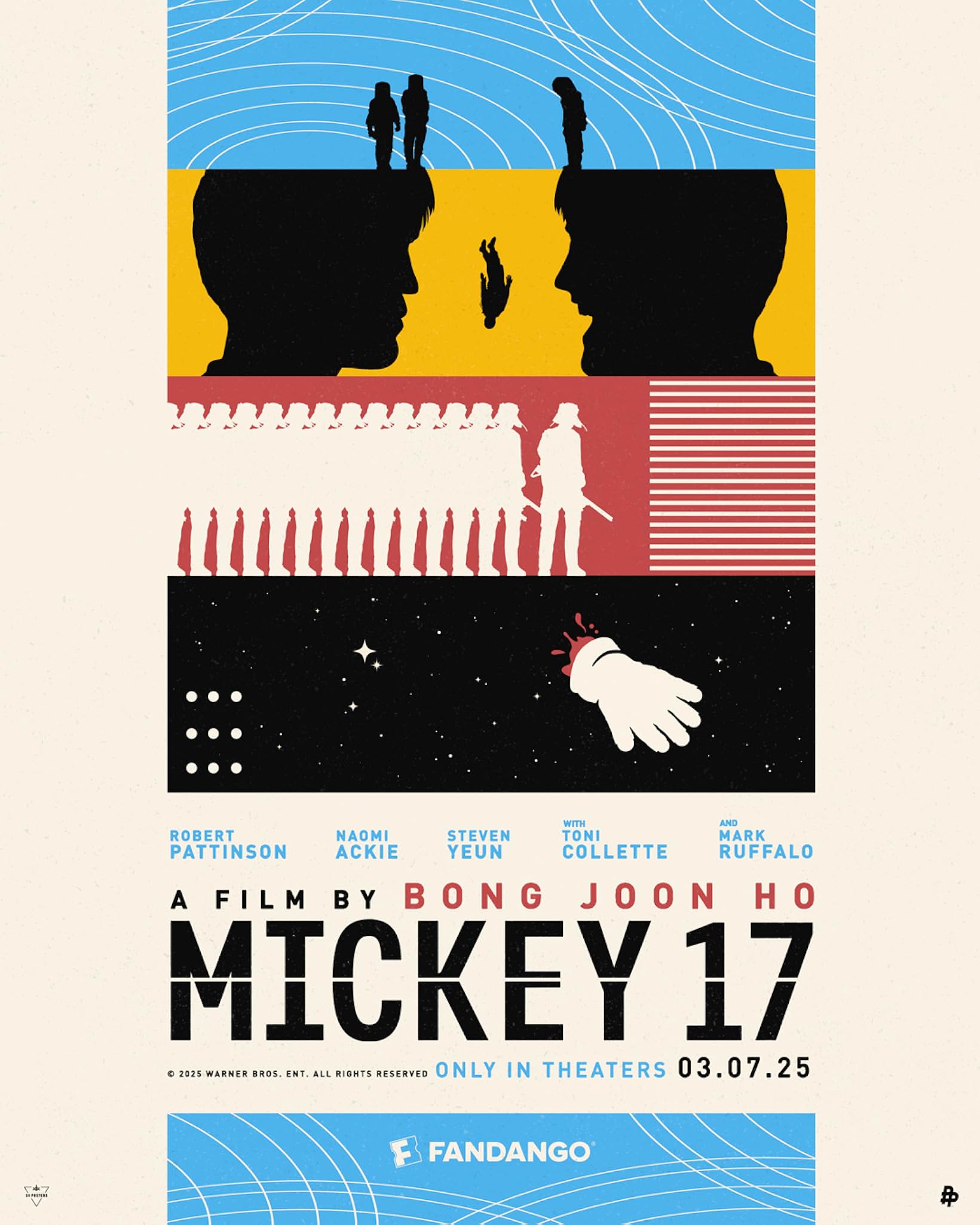

“Mickey 17” (2025) is an adaptation of Edward Ashton’s 2022 novel, “Mickey 7” and the latest film from one of the greatest living directors of our time, South Korean director Bong Joon Ho. It is Bong’s second English language film. Instead of staying and facing his problems, Mickey Barnes (Robert Pattinson), a gullible pushover, is like a lot of people in his time—he leaves Earth for a four-and-a-half-year voyage to a distant planet, Nilfheim. Without reading the fine print, he exchanges being in a lot of debt, which has the potential of leading to painful torture and death, to becoming an expendable, which is a guaranteed eternal life of torture and death. He permits himself to be cloned, i.e. printed (ink jet, not laser), every time he dies. His memories are backed up onto a brick like looking external drive to later be downloaded into his next body. Unfortunately, most people see Mickey, the lowest rung on the ladder, as the equivalent of a lab rat or crash dummy. When an accident keeps him away from the ship for too long, Mickey 18 (also Pattinson) gets printed, but multiples are illegal, and they will be executed with their memories destroyed. Mickey resists obeying orders and dying. What does it feel like to live?

I’m not a Pattinson fan. After years of hating him, now that he has defied the broken clock rule, i.e. was good in more than two movies (“The Batman” and “Tenet”), I must let it go and admit that he is great. When you go to a screening, the only downside is not being able to see the movie repeatedly immediately. Mickey 17 is such a pathetic schlub down to his voice which sounds like a low level, ineffective gangster from a black and white film. He just accepts his circumstances with no resistance while the world around him is mostly indifferent to his endless suffering except the data that they derive from his pain. His “job” is basically to acquiesce to a team of scientists with Mengele’s to do list but the demeanor of a subservient, awkward screw up. Bong is more polished than Terry Gilliam, but the film has that screw up, distorted, comical vibe.

Dorothy (Patsy Ferran) is the only scientist who cares about her job and duties and attempts to treat Mickey and his bodies with a sense of dignity and respect. Matthew (Michael Monroe) is more like the average scientist and sees his job as busy work that can run itself while he entertains himself. Unbothered by the moral implications yet cognizant of them, Arkady (Cameron Britton), the chief scientist who reports to the leaders, Kenneth Marshall (Mark Ruffalo) and his wife, Yifa (Toni Collette), takes his job seriously. This team is indifferent to creating miracles or abominations of life, which is emblematic and portends how they will treat other forms of life. It would be almost impossible to watch the casual cruelty if Bong did not have a sense of humor and visual acumen to know the precise point to give his audience a break.

Only members of the elite security team, who seem to mostly consist of women, see Mickey 17 as a person and socialize with him. Zeke (Steve Park) is the head, but has a gentle, soft-spoken demeanor. Nasha (Naomi Ackie) is a physically impressive, irreverent agent. Kai Katz (Anamaria Vartolomei) is considered the ideal woman according to that heteronormative society’s standards in terms of reproductive selection but appears to be bisexual or a lesbian, which means that she is not the heteronormative ideal. In the middle of one of Marshall’s endless speeches, Nasha and Mickey 17 lock eyes and become a couple. Without one part of society seeing Mickey 17 as a human being, that society would be worthless, but they act as salt and season the community so it can gradually morally course correct starting in Niflheim and expanding throughout the galaxy. It is a story about colonization, and if the colonizers hate themselves, there is not much hope for anyone else.

Through these relationships, Bong gives a subtle blueprint for resisting fascism and dominant class cultures: know which orders to disobey and follow your natural instincts. Unlike most dystopian stories, “Mickey 17” sees the military as a source of hope and protection, not a colluding threat. Apparently before World War II, the principle of unquestioning obedience, i.e. top-down command, drove the military, but post-World War II, it is mission command, which means anyone in the military can disobey an order if it is illegal even if the order is coming from a person with a higher rank. No one can hide behind obeying orders for bad conduct. On a more elemental level, they obey their nature. They have sex, want to help someone if they are in pain and are unable to filter information through the demented Orwellian thinking of the ruling class.

Normally a writer would choose a protagonist from the security team group or at least someone who is brave and can fight. Mickey 17 has almost no admirable qualities and has been brainwashed into obeying the ruling class’ lessons about himself. He is plagued with guilt, sees life as a punishment and for much of the movie, his memories filter out or misunderstand kindness. Though replaceable, he is an individual and unique. For me, “Mickey 17” was a spiritual experience. Even synthetic generated life is unique and special, i.e. each Mickey has a soul, a personality. As human beings, you do not have to do anything for society to deserve to live, which means having the right to physical autonomy, appropriate work hours, being a spokesperson for society, being an accepted part of society, having a place to sleep, eat, not being abused, etc. Life is the miracle even if it is taken for granted. Mickey 17 is an accessible hero. If he can find a way to stand up against an oppressive society, anyone can.

Also, Mickey 17 is not masculine though Mickey 18 is and laudable in his own way almost like his angry side split off, but ultimately unsustainable. Mickey 17 follows the Biblical principles of husbands who are supposed to be devoted to their wives. He understands that Nasha is out of his league, but he does not try to bring her down to his level. Instead, he supports her as a powerful leader and enjoys his great luck because she finds him desirable. Mickey 17 appears to be a secret catch in this society because he has no need to feel dominant, but he also gets jealous and possessive without following that impulse to its natural conclusion.

“Mickey 17” works because it does not believe in perfect happy endings. The oneiric sequence is chilling and suggests that this desire to print our worse selves always lurks in the corner. Mickey 17 may survive, but everyone bears the mental and physical scars of trauma. There can be mending, but the feelings linger. It is interesting that Mickey 17 cannot resist and live until he meets living beings outside of his society who start that healing process and have an innate respect for life even when it is not reciprocated. Bong still has it, and if the man who made “Snowpiercer” (2013) and “Parasite” (2019) can make an optimistic, instructional film at a time like this, there may be hope for humanity.