“Meek’s Cutoff” (2010) is loosely based on the historical events of 1845 when a Westward bound group of Americans decided to follow Stephen Meek with dire consequences. Kelly Reichardt directed this film, and it marks her second collaboration with Michelle Williams after “Wendy and Lucy” (2008). Reichardt’s films are sympathetic to the characters, but have pitiless, stark plots with sparse backstory.

“Meek’s Cutoff” is the kind of film that is better viewed in a theater on a big screen than in home with distractions. The film is a reasonable length, one hour forty-four minutes. The dialogue increases proportional to its proximity to the denouement, but even then, the most crucial character revealing moments could be missed if the viewer is not rested and attentive. Do not watch this movie purely for entertainment purposes. If you want to watch this film to learn about American history, it would probably be a better idea to switch your focus from history to sociology. Reichardt is less interested in recreation than exploring how gender, race and relationships influence power dynamics in a vacuum, a wasteland, where survival should be the only goal. The events in the film feel more like a reimagining of untold history than a chronicle.

“Meek’s Cutoff” depicts a tension between reality, which is visual, and imagination, which is words. Reality is uncompromising: day or night, water or dry, cracked ground, live or die. It is as unclear for the viewer as the characters whether they are nearing their destination, especially during a time lapse sequence early in the film. Sometimes it seems as if they are retracing their steps, but their existence in the present is unequivocable. It requires hard work that may not be rewarded but is the bare minimum to survive.

The imagination in “Meek’s Cutoff” is a broader category that contains words and assigns meaning to reality. Treasured memories embodied in belongings soon get discarded as burdens. Stories are told. The Bible is read and recited. Descriptions of hell entertain a child—it is filled with hills and bears, the obstacles of prior emigrants. For these emigrants, the film asks a silent question: how would their reality influence their image of hell? They are aware that if they survive, this experience will become a story. Societal rules are also stories to entertain adults: race, religion, wealth, status, and power.

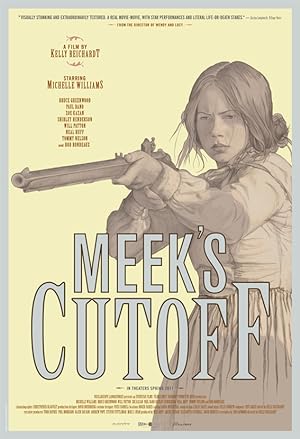

The opening scenes of labor puncture the myth of protecting white women. They are working as hard as the men and appear to have longer hours since the men’s labor includes making life and death decisions, which requires a lot of tongue wagging, but no sweat equity while deliberating. Reichardt shows the women outside of this sphere of influence hoping to hear what their fate will be, without a vote, which has made people classify this film as a feminist Western. When the women talk, they exchange information gleaned from their husbands, which is the only way that viewers can infer the health and nature of the relationships that we have seen without any explanation. The Tetherow marriage seems to be the one closest to our image of a functional relationship though it is a May December match between Soloman (Will Patton) and Emily (Michelle Williams). Emily may be young, but she expresses herself freely compared to the other wives. She also appears to have at least one practical skill over the other women and most of the men as the poster art demonstrates.

When the women talk, their first two discussions are about race and rumored deliberations about punitive justice and race. “Meek’s Cutoff” presents this absurd dilemma of execution, a theme throughout the film with different targets. When survival seems doubtful, the emigrants seize control by considering taking away another person’s autonomy-the single person is always vulnerable. The first potential victim of this frontier justice is the titular Meek, Stephen (an unrecognizable Bruce Greenwood). He is a braggard who enjoys the sound of his voice. Lack of results do not quiet him, and at least one or two of the male emigrants still listen to each word as if it was gospel in terms of wealth and adventure. He correctly senses that the women tolerate him. Emily questions the source of his errors: evil or ignorance, but the result is indifferent to and unchanged regardless of motive. For these characters, the superimposed narrative dominates their mind. The second single person is a Native American.

Race, which should be irrelevant in this context, becomes a much-discussed commodity. The emigrants’ innate, undeserved arrogance and entitlement makes them resentful when they must work like “n” (a line that Shirley Henderson delivers in her unique, instantly recognizable, chilling voice) and their imaginary fear of Native Americans is absurd when they are the ones trespassing and committing crimes. It is one of those moments when as a black viewer, you are happy for the lack of representation of all races. Happy to sit this one out. When a Native American man gets introduced, he becomes the emigrants’ lightning rod for their fears and hopes though they don’t understand him (literally they do not speak his language, but shared knowledge would not help this crew). Meek does not pay forward the mercy that he received though incompetence does not warrant implementation of the death penalty. While Meek’s prejudice is period appropriate, there is a subtext that this nameless man poses a threat because he may displace him as the guide.

My favorite part of Reichardt’s approach was not creating a gender moral divide. In many ways, the women are more biased than the men. While Emily is more reasonable in her interactions with the Native American man, she is not some fount of progressive enlightenment. She is practical and uses kindness like an investment by giving him food and mending his clothes. She makes the same bet as her husband. If this Native American man can survive, they can survive by following him.

“Meek’s Cutoff” gives time to Ron Rondeaux to create his character. He is not fooled by Emily’s kindness and seems amused when one of her plans backfires spectacularly—it is the only moment when she seems defeated during this journey. While he is not the evil mastermind that most of the emigrants imagine, he is not rooting for them either. He is like them-exhausted without help or with no guarantee that he will survive this journey. Unlike them, he did not make a stupid choice for wealth. (One character is named Millie, and by the end, I called her “Miss Millie.” If you know, you know.)

“Meek’s Cutoff” feels as if it ends too soon. When Emily takes a definitive stand regarding the group’s destiny, everyone looks at her differently. I was transfixed at the idea that all these men decide to kidnap this man without consulting the women, but only Emily has the stomach to follow through on their plan. They treat her with suspicion, and I would have loved if Reichardt explored that more, especially its effect on the Tetherow’s marriage. The fear of the other is stronger in most of them over the fear of death, and it is the only point when most consider turning around.

If you do not like ambiguous endings, you may not appreciate “Meek’s Cutoff” though I do not consider it ambiguous. It is history. You can find out with a simple Google search. Reichardt’s ending presents a better decision-making system than the one that got them into this mess. The women get a vote, but now Emily and the Native American man will get the blame if their plan does not work out. Millie openly objects to her subjective terror. What if they succeed? Even this slight improvement holds no staying power once they reenter society.