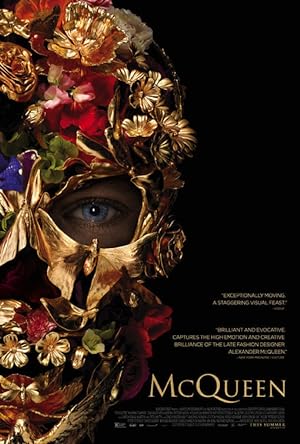

McQueen is a documentary about Lee Alexander McQueen, who ascended from being on the dole to an internationally notable fashion designer. It chronologically explores his life, professionally and personally. It is divided into five parts or tapes with a title borrowed from his shows. These shows were closer to performance art than a traditional runway fashion show and were autobiographical. They had the atmosphere reminiscent of American Horror Story, but actually explored his psychological journey and his inability to exorcise the demons of his past.

Even though I am into fashion, I’m not going to pretend that I went into McQueen knowing anything about him or had a long-standing appreciation of his work. In a vacuum, his work would not necessarily appeal to me. For me, being a New Yorker has the side effect that the more shocking someone is, the less attention that I give that person, and I tune the shocking out like white noise. I understand that objectively, for me to respond that way to this particular designer’s work means that I’m a Philistine, but shrug, I suppose that I am, but even he managed to puncture my force field with Savage Beauty, a posthumous 2011 art exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which I sadly missed, but my friends rapturously told me about, and I resolved to see if it ever came my way, which it never did. So when this documentary hit the theaters, I went to see it on its first day.

McQueen would be perfectly paired with Whitney as documentaries that provide broader socioeconomic and cultural context to artistic genius that ends in tragedy while still embracing the intimate details shared by those closest to the titular figure. The film uses home videos and archival footage. Instead of talking heads, we get perspectives from family, friends and colleagues about his life. Unlike Whitney, the documentary provides a rigorous analysis of the man and his work. He starts by gaining technical experience then gradually begins to embrace fashion as a way to tell a story while using external influences to craft that story. Also as he moves away from the streets of London to couture in Paris, he begins to soften his style, but harden his openness to life as he experienced rejection from those who thought that he was a yob trying to destroy Givenchy. He then brings couture back home and is able to strike a balance between high art and street sensation during his time with the Gucci Group. So for fashion Philistines, we get a guide in how to analyze the significance of his work on its own terms, creatively, internationally and in terms of objective market value.

McQueen may be a creative genius, but he was also a practical one even at the height of his despair. It struck me as unusual, and I found it endearing that even when he was committing suicide, he thought of others’ financial welfare and sought to provide opportunities to others like him, from humble, working class backgrounds by establishing a scholarship called Sarabande. He realized that this business affected the livelihood of others and respected the working class whom he employed because he never forgot his roots as a tailor. McQueen may have briefly embraced his Phantom Thread side, but he never really thought of himself as a king. He was even considerate of his models casually guarding their modesty from prying eyes. Unfortunately this literal and psychological burden prevented him from taking a break. As Banksy wisely wrote, “If you get tired, learn to rest, not to quit,” which is an extremely difficult concept to embrace when you suffer from mental illness whether it originates from trauma or inherit it. I was also impressed that he did not conflate his exhaustion with his profession and never discouraged others from pursuing a life devoted to fashion. He singlehandedly lifted his family out of poverty and gave opportunities to his nephew, which showed that while wealth and fame may have contributed to his downfall, as a person who always cared for others’ well-being, on an instinctual level, he never blamed wealth or fame for his eventual demise otherwise he never would have exposed those that he loved to it.

Similar to Houston, McQueen used drugs as an unhealthy escape and lost a sense of his identity as he cultivated a public persona, which he knew was not real. Like the pop star singing sensation, he surrounded himself with friends and family, but unlike her, they were willing to separate themselves from him financially and had his best interest at the center of their relationship. They were with him because they wanted to spend time with him, and they genuinely enjoyed the work. Just from watching their interviews, I could tell that they were able to cultivate a rich personal and professional life outside of him, which is why they tried to intervene. They had nothing to lose, but their friend.

In the end, just as his mentor, Isabella Blow, decided to exit on her own terms after suffering from cancer, McQueen took a similar route after suffering from bouts of ultimately terminal depression possibly brought on by childhood abuse. Instead of taking their lives, they gave themselves to death. While I understand that the documentary was trying to respect McQueen’s privacy by not delving into the details, I actually thought it was germane considering how his shows were considered misogynistic, but they were actually autobiographical. He saw himself as one of the models so we can fairly infer what happened to him. He seemed to draw a link between his personal experience of abuse and a heritage of abuse stemming from the “genocide” (his terms, not mine) of the Scottish by the British. As he got thinner and more elegant, he began to emphasize his Scottish heritage by wearing kilts. It does not seem as if it was only a way of embracing cultural heritage and pride, but articulating trauma. Unlike people like Shirley MacLaine, he does not simply reduce history to the glorious moments, but recognizes past pain as a continuum that stretches into the present.

McQueen was refreshing because his sexuality never took center stage or became a segment of the film. His former boyfriends share aspect of their lives in interviews, but there is no time devoted to the mechanics of being gay in a straight world. Instead it is a given, an aspect of his life although it could be seen as implicit considering the choice of his profession as contrasted with his father’ hopes that McQueen would adopt a more blue collar profession. It was just nice for his sexuality to be a characteristic of his life, a given, utterly normal.

While McQueen may have shared one personal vignette too many or showed one home video clip for too long, overall I highly recommend McQueen. While it was more depressing than I expected, it is one of the few times that I did not feel angry, frustrated or wrapped up in my own mixed emotions at hearing that someone died by their own hand. I think that the film effectively conveyed McQueen’s story, and it taught me a lot about fashion and his struggle to live. (Side note: if someone had just shown me photos of McQueen without the backstory, I would have considered him the living definition of glow up.)

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.