This review was originally published on Roarfeminist.org

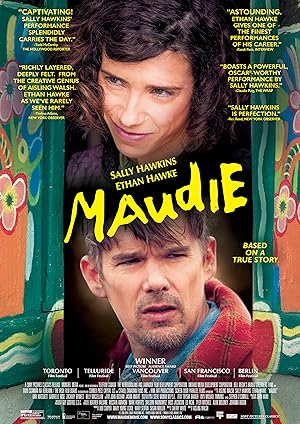

I trust Sally Hawkins. She starred in Mike Leigh’s Happy-Go-Lucky. She takes characters that others see as odd and makes them real. In another actor’s hands, her roles could turn exploitive or cliché. She shows us the corners of her characters’ minds and wordlessly communicates volumes with her glance. So if she thinks that she should star in Maudie, I think that I should see it, and I did the weekend that it opened in my city without knowing anything about the titular character.

Maudie is a period film set in the 1930s through the 1970s and an unconventional biopic about a Nova Scotia woman named Maud Lewis, an unlikely adventurer who finds her place and voice in the world. This journey is not like most adventure stories, and Maud is not like most adventurers. Maudie challenges us as viewers to ask ourselves how we see others and ourselves, why do we think that life should be lived a certain way, what is and is not acceptable, how do you become yourself, how do you become fulfilled as a three dimensional human being, and how do you know who your people are.

For the majority of the first half of Maudie, other characters only have negative interactions with her. They see her as a burden, damaged, an inconvenience, an embarrassment, a scapegoat, a wanton and shameless woman. Her first kind interactions are brief and with strangers: a customer and someone who works with her employer. Even though the film is based on a real life figure, Maudie had a Jane Eyre flavor in its depiction of Maud’s relationship with her family. She loves them, but flees at her earliest opportunity. Later revelations confirm that her instincts were prescient. Jesus knew that “a prophet is honored everywhere except in his own hometown and among his relatives and his own family.” Her family reflects society’s view of Maud, but they are ignorant of her inherent worth as a person. They deny themselves the pleasure of her existence.

Maud knows her worth and values her work. She sets clear boundaries with them without becoming bitter and values her autonomy more than security. Psalm 118:22 notes that, “The stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone.” Maud has an inner strength to not be defined by others’ unkindness or judgment and is self-possessed enough to know what she wants and needs, and then gets it. Hawkins makes her soft-spoken and kind, but also observant, clever and trenchant even in her deferential moments. Her actions are independent of others’ view of how she should live. She embraces her virtues and vices equally then guards both fiercely. She does not define herself by her obstacles. She simply and fully lives in the present.

Maudie does not depict her life choices through rose-colored glasses, and many of her choices are questionable. There was more than one occasion when I would have run screaming the other way, and many of her fellow characters urge her to do so. Many categorize Maudie as a romance film. Um, pardon me, I hope that is not your idea of romance. Don’t ask me out. Ethan Hawke plays his least Ethan Hawke-like character as her employer and later husband, Everett Lewis, a wounded and clenched grown orphan who thinks explosive, laconic derogatory abuse is the best way to interact with his live-in housekeeper, later wife, and provides early inspiration for Manson in his views of the hierarchy of living beings on his property. Maudie never flinches from showing Everett at his worst or excuses his conduct, but also shows him as a three-dimensional character capable of adjusting, responding to, nurturing and encouraging Maud. Even at his best, Everett still hides and when cornered, falls into his comfort zone of lashing out. He is afraid of needing someone else and not deserving love so he repels people before they can hurt him. I have never seen Hawke disappear into a role before this film.

People are not always perfect or awful. Maudie presents them as multi-dimensional, though severely flawed. When Everett turns his cussedness towards the outside world to create a sanctuary for his partner, she gets levels of support that most women would only dream of, including his rejection of any criticism of her work from the locals. His behavior is incongruous: he regularly says unkind things, but is stunned into still silence when she mentions unkind behavior from others. When he reluctantly abandons his need to be dominant and his insecurities of being unworthy or less of a man for loving an odd woman, they are their best selves. The film constantly asserts that life is at its best when we abandon our notion of how it should be lived.

I am not familiar with Aisling Walsh, the director, but she visually captures them as mirror images of the other in scenes where they look at each other through windows: initially dirty, then clear, then painted and finally empty. The happy pair are shown silhouetted against the expansive sky as he pushes her on a cart to their destination in long shots that communicate their togetherness. Her shots of the landscape during the changing seasons and the emotional intimacy of the pair reflect Maud’s real life inspiration for her paintings. Maudie is a lush film even during the barren, harsh winters. She wisely devotes the final scene to show a video clip of the real life smiling couple in their little, colorful home.

If you are fortunate enough to live near a theater showing Maudie, I would admonish you to go see it and be encouraged to live as bravely and boldly as she did.