Set seven days preceding September 16, 1977 in Paris, “Maria” (2024) is the last entry in Pablo Larrain’s trilogy of biopics about iconic, mournful, elite women, which some call his “Lady with Heels” trilogy. The first, “Jackie” (2016), covered Jackie Kennedy after the assassination of her first husband. The second, “Spencer” (2021), covered Princess Diana’s 1991 Christmas, which was the last that she spent in a sham, unhappy marriage. This last film covers Maria Callas’ final days as she decides when to sing her swan song, and those closest to her try to get her to focus on her health and future, which means accepting and relinquishing her voice. Angelina Jolie plays the singer in her final days.

“Maria by Callas” (2018), a documentary about the opera singer, left a lot of room for a biopic to fill in the holes left about the singer’s life outside of the spotlight. Writer Steven Knight, who wrote “Amazing Grace” (2006) and “Eastern Promises” (2007), takes the delusional famous lady route to fill in the blanks as he did in “Spencer” and writer Abi Morgan did in “The Iron Lady” (2011) with former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The titular character, Maria, deliberately takes drugs, specifically Mandrax, to look back on her life and have an imaginary adoring interviewer, deliberately named Mandrax (Kodi Smit-McPhee), and a silent Cameraman (Kay Madsen) to help spur her on her quest to reclaim her voice and reflect on her life. A pharmaceutical induced vision quest alarms her devoted servants, housekeeper Bruna Lupoli (Alba Rohrwacher) and butler Ferruccio Mezzadri (Pierfrancesco Favino), who seek help from Doctor Fontainebleau (Vincent Macaigne). When she interacts with people who are not a part of her delusion, Maria gets easily frustrated and angered though she maintains a soft, calm tone.

Maria is a diva with most people but is considered such a consummate artist that everyone gives a lot of latitude to her. To be an artist, there must be some madness. No one considers how she is ruminating over trauma to marinate the music, so it has more flavor, but not getting over trauma puts her in danger of her imaginary life swallowing her whole. This trauma includes her mother’s off-screen abuse, which would leave her at the mercy of Nazis, unsuitable peacetime suitors and the loss of her voice. Art gives, but it takes. Her mental exercise, which is structured as if Maria is participating in the filming of a documentary, is a final act of autonomy over her life.

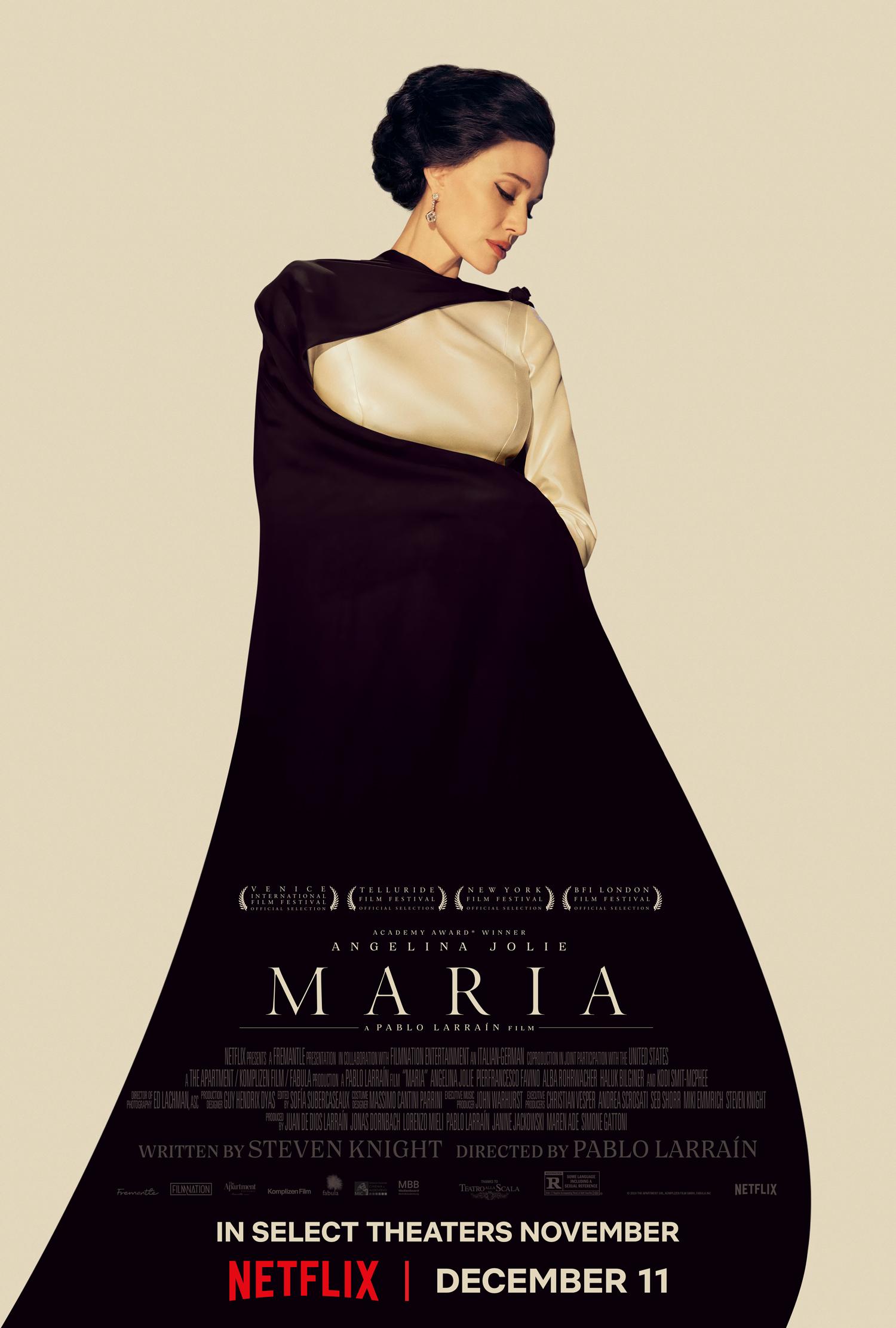

“Maria” is a gorgeous film whether Maria is walking through an early autumn Paris, gliding through her stately apartment or singing in an empty hall. The flashbacks take two forms: recreated excerpts from archived footage of the singer or black and white crisp memories. While it is more structured than the documentary, it still feels fragmented and incomplete. These films prioritize the Callas of collective memory by wisely leading with Callas’ singing voice instead of an inadequate substitute and recreating her opulent looks as if offering a live action glossy magazine. It is almost as if there is something about the real-life Callas that makes filmmakers reluctant to stare at her directly as if they risk being blinded. Like Stewart as the People’s Princess, Jolie’s real-life star power and controversies add an extra, subliminal layer to an already mesmerizing performance about a lone diva comparing her image to the reality and finding herself inadequate. Her acting fills in the script’s blanks, and it feels long overdue that Jolie finally gets a prestige product as opposed to the middling crap that never dulled her shine, which apparently includes a tumultuous marriage.

The strongest scene is between Maria and her sister, Yakinthi Callas (Valeria Golino from “Rain Man” and more notably “Portrait of a Lady on Fire”), the only person who can approach Maria as an equal and a human being. It does not hurt that it is a scene in which the dialogue spells out Maria’s internal conflict during the imagined final seven days. In the end, Maria transforms into another opera heroine who dies, but on her own terms—the triumphant and literal ultimate curtain call. No one let Celine Dion see “Maria.” There are too many uncomfortable similarities between the two singers who lose their voice, which Dion detailed in her equally sumptuous autobiographical documentary, “I Am: Celine Dion” (2024). When a person feels as if they exist to serve one purpose, whether it is a person or an audience, it feels like a tragedy, but is relatable. The capitalist mindset is not just limited to money and incudes worth related to usefulness.

“Maria” feels like an unofficial sidequel to “Jackie” because of the role that Aristotle Onassis (Haluk Bilginer) plays in both women’s lives: Callas’ lover and Jackie’s second husband. Caspar Phillipson plays JFK in both films too. Portman does not reprise her role as the famous first lady, but her presence is felt. Like Jackie, Callas was married when she met Onassis, so she knows his schtick, which he does not hide from her, but openly flaunts. JFK approaches Maria as if he intuits Onassis’ intentions, wants to confirm them and perhaps recruit Maria into a little revenge. It is one of those scenes that speaks to the character’s dignity and self-awareness of her superstar status in society, but also feels as if it needed elaboration or to be omitted entirely. If “Jackie” was about the betrayal of widowhood and “Spencer” was about the betrayal of marriage, then “Maria” is about the drawbacks of freedom and accessibility, which leads to opening oneself to the boorishness of Onassis, trying to rid himself of Maria so he can pursue his next conquest, and JFK, trying to stock and protect his stable. JFK offends more than Onassis, but the movie never conveys Onassis’ appeal.

If there is a root problem at the heart of “Maria” and “Spencer,” it is the fact that Larrain and Knight’s biopics seem fictional even when they contain accurate details. Callas did have two devoted servants who were Italian, but with the piano moving antics, it is easy to believe that no one would stick around for long. Onassis allegedly enjoyed drugging his conquests, including Callas, and Callas seemed to fear, not adore, him. Because there is little general knowledge about Callas’ life off stage for those who are not seasoned fans of the opera singer, anything sounds vaguely right and is so ephemeral that it floats away just leaving an impression. While biopics are not required to accurately depict its subject, it would be nice to get a more substantial film than something that could easily be cut into thirty second spots and work just as well as a commercial for a perfume or some other luxurious product.

Jolie is a triumph who puts meat on the bones of a thin sketch of an iconic woman, but both Jolie and Callas deserve a biopic that will stay with its viewers more than a few minutes after the lights come on. You will still leave with plenty of questions. Was she really called “The Callas?” Were her final moments as devoted to giving love to the masses as Larrain would have us believe? How was she different from her contemporaries and how did that make her special and doomed to meet a curtailed end? “Maria” may be a success if it inspires moviegoers to learn more about Callas, but none of those answers can be found here.