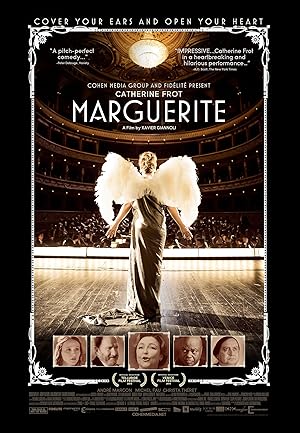

Marguerite is a French film starring Catherine Frot, whom I adore from Haute Cuisine and The Midwife, as the titular character. Florence Foster Jenkins is the real life inspiration for this film. Marguerite was made and released before Meryl Streep’s Florence Foster Jenkins. I decided to watch both films and a documentary, Florence Foster Jenkins: A World of Her Own, in one sitting to explore what aspects of this real life figure resonated with so many people at this particular period of time over seventy years after her death paying particularly close attention to the fictional parts, which the filmmakers crafted to further whatever point that they were trying to make.

Marguerite feels like a film in need of a better editor and/or writer and succeeds in spite of its structural flaws. It is divided into five chapters, but a better term would have been acts because one of the characters envisions Marguerite as the tragic heroine in an opera, and the film seems to agree with his characterization based on the trajectory of the plot. The majority of the film feels like a slapstick comedy, especially with the husband’s repeat interactions with his car, and a joyous journey of fulfillment and self-discovery for the dreadful singer, but in the final act, there is an abrupt shift.

Marguerite is set soon after the Great War, a time when France was emerging into a modern era strong, but also reeling from a lot of death and destruction, which creates social upheaval. She seems to act as the soul of France-being used by those in power, betrayed by those who should love her; being unwittingly used by those without power who are somewhat mocking, but also present an opportunity for her to live a fresh, new active life instead of just continuing in the same, stultifying fashion. People struggle over her and try to take the country in various directions when all her efforts are to win the love of her husband through singing, which is impossible because her singing is dreadful.

People in her class tolerate Marguerite because she sticks to her lane by limiting her ambitious productions to her home, financially supports and socializes with them. She does not notice that everyone is lying to her. It is only when someone crashes her world, the younger generation, that she gets exposed to people outside her bourgeois world and begins to interact with the fringes of society: leftists, younger people, people who do not adhere to traditional gender roles, etc. She is invigorated by this change in scenery, but still does not quite understand her place in the world or how her actions will be interpreted by those that supported her. She unironically asks, “Aren’t we free to sing the song of freedom,” unaware that the song of freedom does not include everyone and by simply singing it sincerely, but badly, she is telling a truth about the failed promises of France to its people, including the colonized. She unwittingly breaks a social contract with the bourgeois while simultaneously still upholding unquestioningly the patriotic beliefs of her nation. Her life becomes a battleground of conflict though she is oblivious to it. She is a sincere, enthusiastic, but incompetent innocent; however this exposure to the broader world makes her vulnerable to the truth, which threatens to completely shatter her world.

Marguerite lives in an upside down world. Those without talent get accolades and have money, but those with talent do not and struggle. Initially the film feels as if it is creating parallels between Marguerite and a young, beautiful, gifted, but poor and unsuccessful singer to make a broader point. A journalist writing a story about Marguerite is naturally drawn to the young woman, but becomes a part of Marguerite’s life instead. The parallels are largely abandoned, but sporadically revisited. There is supposed to be a comparing and contrasting of young love with a marriage of convenience, but it goes nowhere and probably should have been completely omitted.

Most people do not want to destroy her so they protect her, but she is also impervious to criticism. It does not hurt that you get rewarded with tons of money. However one of her fiercest protectors has his own artistic agenda, and while I won’t spoil it, I was asking myself throughout the film why there was only one black character and why was he so invested in her projects. In retrospect, even though he is French, I wonder if he is supposed to represent the colonies—devoted servants, but to what? If there is a villain in Marguerite, Madelbos is it because he understands and supports her, but not out of love for her. They do not have the same goal though they are entwined in the same project. While he may not be the cause of the denouement, he celebrates and anticipates it in a way that none of the characters, including those responsible for it, do.

While I considered him mean as I watched the movie, and I’m not wild that the single black character ultimately becomes a sinister figure, I did appreciate the reality that as a servant and a black man, an invisible man, the man behind the curtain, he would see more than anyone else, even those who claim to be rebels, but are just as complicit in creating the lies that prop up Marguerite’s world. Their assumption that he is doing it, like them, out of love and kind feelings, is a crucial mistake. He is a servant to a buffoon, not a guest. He is doing it out of survival and out of his own agenda. He is creating her world with a subversive goal. “If it can be destroyed by the truth, it deserves to be destroyed by the truth.” He becomes a director figure reclaiming his work and understanding the truth in a way that no one else can bear to do though they all claim to want it. He really lives in the world of lies in a way that most of them don’t—they can escape and take breaks.

Marguerite’s dramatic tone shift is the most surprising element of the film after one perfect moment of transcendence when Marguerite achieves all her career and psychological goals, but it can’t last because all of it rests on a lie. There is an idea that tragedy could have been prevented and talent could exist through the power of love, but it is too late. Her confrontation with the real world exacerbated by this lack of love is ultimately out of anyone’s hands.

In the end, like the soul of France, when confronted with the reality of her talents, her relationships, her delusions, she is shocked by the truth. Her inability to fully see herself was necessary for her to exist as she is. While Marguerite is just a movie and cognitive dissonance does not generally have such a ridiculous deleterious effect on people, I think that it works on a symbolic and operatic level. If you confront the reality that wanting to be great and devoting all resources to a goal may still mean that you’re a failure, what does that mean for a person unwilling to imagine any possibility outside of success? If France’s delusions about itself as a nation on the world stage, as a place that treats all of its citizens, including the colonies, with liberty, equality and fraternity, that it is beloved by its people are suddenly shattered, what does that mean for France or any country or political, socioeconomic system not rooted in merit, but in a belief that is not rooted in reality and irrationally believes in its superiority and fails to look at its failings and accept them? Marguerite shows that love, even well meaning, protective love is destructive if it isn’t true.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.