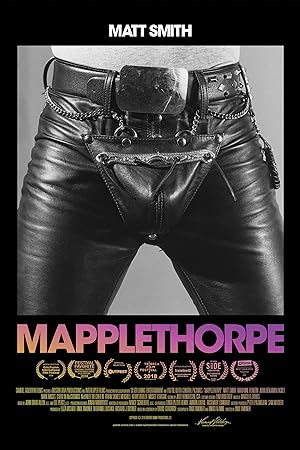

I was really excited to see Mapplethorpe. I loved the preview and was even planning on going to a special screening featuring the producers discussing this film, but life got in the way. After two weeks, it appeared that it was going to be pulled from theaters, which was not a good sign, but I was not deterred because maybe theaters and the public were wrong. Sadly they were not.

Mapplethorpe is largely a lackluster biopic starring Matt Smith spanning 1966 through 1989. Fair or not, I compare all biopics about notable gay artists with Tom of Finland to make sure that subconsciously or not, the film has not absorbed any latent homophobic tendencies and slipped into the tragic gay trope of being sad and alone then dies like Camille. If How to Survive a Plague could center people literally dying of AIDS and still have a sense of joy, exuberance and vitality about the person embracing their complete identity, then I don’t think that it is unfair to expect the same from a drama. To be fair, I’m not familiar with the titular character. Maybe he was a sullen, joyless drug and sex zombie near the end, and the movie is brilliant, but I just can’t entirely believe it. Creation of such beautiful work must be at least momentarily exhilarating even if it subsides.

It was entirely too late in the whole proceeding when I realized that what attracted me to the movie was Mapplethorpe’s photographs, which are fully displayed in this film. If the movie had simply been a one hour forty-two minute slideshow, it probably would have been better. There are numerous scenes depicting how the artist created the photos, but no matter how gorgeous the actual actors are, they are not the subjects in the photographs, and the movie can’t pull off making the viewer feel as if he or she were there at the time of its making.

Mapplethorpe succeeds at shooting the film in the same style that was used in that era, which is quite an accomplishment. I normally enjoy that stylistic choice, but it had the actual effect of constantly reminding me that I was watching a movie. It kept me at arm’s length, especially the early scenes from the 1960s and 1970s. I’m not sure whether or not when I saw that in the past, it worked because I was watching it at home so maybe this movie will do better with home viewing, but on the big screen, I never could get lost and forget that I was watching actors play a role while everything was being shot just so.

I’m not sure if Mapplethorpe’s problem lies in the film or the actor because the film did have two bright spots: John Benjamin Hickey, who plays Sam Wagstaff, his lover and benefactor, and Tina Benko, who plays Sandy Daley, a neighbor, artist and mentor who turned him on to photography. The movie actually came alive when they appeared, and I wanted the movie to ditch its subject and go on a detour. When Wagstaff started talking about serving in WWII, I thought, “When do we get a movie about that man.” Daley has some of the best quotes in the entire film, “You think that if Michelangelo had a camera, he wouldn’t use it.” I was completely absorbed in their performance and believed that they were their characters.

We’re told that people trust and love him, and his friends are the subject of these photographs, but Mapplethorpe gives us another impression. He feels as if he uses the camera to dominate them, and in one depiction, it feels vaguely abusive and manipulative. He generally feels distant from his subjects. There is consent, but not enthusiastic consent, or it feels reluctantly and resentfully transactional, and the film seems to question whether his art was actually fetishizing black bodies instead of glorying and elevating them. To put it in simpler terms, was he vaguely rapey and racist? It never occurred to me to ask that question after seeing his work, but after watching the film, I left with that concern. I hope that there are some documentaries about the artist that fully explore him in order to confirm or deny these details.

Mapplethorpe seems to be engaging in armchair psychology, which I have no problem with, and suggesting that he was compulsively replicating his father’s abusive behavior in his work and some of his personal relationships, particularly his brother, by denigrating their work or their character. (Big disappointing moment: the film shows his father seeing his work, but never shows his reaction to his son afterwards. Do they never see each other again?) Even though I doubt whether in real life, his friends and family drew such firm boundaries, I did appreciate how the film modeled for its audiences how to place oneself first, regardless of your affection for the other person, and not compromise your desires or identity to get crumbs in the relationship that you’re invested in.

I think that it goes without saying, but a movie titled Mapplethorpe is going to have nudity and sexual depictions if only because his photographs were graphic. For example, there is one photograph featuring fisting. The movie reflects Mapplethorpe’s attitude towards sex. As he gets more comfortable and less hesitant about being attracted to the same sex, we get more exposed to representations of it whereas early in the film, we mainly see him lying around with his girlfriend, Patti Smith. If you are not comfortable watching this progression, I would not get anywhere near this film because this should not be your first experience testing your visual limits. It isn’t worth it.

While I’m happy that I saw Mapplethorpe and applaud the filmmakers’ efforts, I did feel disappointed with the overall work and am open to suggestions of other documentaries or movies that did a better job portraying the artist. I don’t think that this film will be the definitive biography of this artist who is still having a huge impact. Has anyone compared his photographs of flowers with Georgia O’Keefe’s paintings? I would love to read an art analysis of that. Chop, chop art historians!