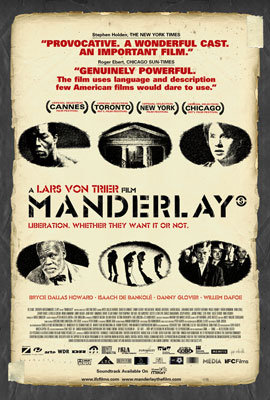

Manderlay is the second of Lars von Trier’s proposed trilogy, The Land of Opportunities films, which are supposed to be set in the US. It is the sequel to Dogville, and while I was even less enthusiastic to see this film than his other films, I still watched it because I am a completist. I watched Dogville and Manderlay in one sitting, an exercise in endurance that I would not recommend that the average film viewer undertake unless determined to watch one of the two films and was familiar with von Trier’s work.

Why was Manderlay the last of von Trier’s films that I wanted to see? On a good day, von Trier’s films have a misogynistic tone that is only diluted by his general self-loathing of men. He is from Denmark, which was a seat of resistance against Nazi occupation, and still managed to be willfully inflammatory in remarks about Nazis (watch for yourself and see Kristen Dunst desperately try to stop him from talking). von Trier writing and directing a film with a majority black cast sounds like a disastrous idea on multiple levels. It sounds like a dare to have a hard drug user paternalistic, misanthropic director who allegedly treats his actors like meat make a film about slavery using black actors-would the racism be accidental or deliberate? Most well-intentioned directors make egregious errors when addressing race so this seemed like a nightmarish scenario, especially since his films are already punishing exercises in excruciating film viewing except now with more offensive content.

It also did not help that Dogville’s Nicole Kidman who played the protagonist, and James Caan, who played her father, did not resume their roles in Manderlay while other actors who appeared in the first film played entirely different roles. Instead the batons were passed to Bryce Dallas Howard and Willem Dafoe who were cast in the respective roles. The lack of continuity was insurmountable. I liked Howard’s toughness and eagerness to wield power, which seemed like an organic reaction to Grace’s ordeals in the first film, but was haunted by what the movie would have been like if Kidman continued exploring her character. Also Howard on her best day is no Kidman, whom I begrudgingly have to admit is an actor deft at projecting genuine emotion at will, but I can’t blame her for giving this film a wild berth because she almost choked to death during the first film.

Manderlay starts soon after Dogville ends. Grace and her father have left the Colorado village and arrived in Alabama to discover a plantation where slavery still exists seventy years after its legal abolition in the US. Grace, fresh from her brush with involuntary servitude, decides to intervene with often disastrous results until she makes a horrifying discovery about the plantation. It is a shorter film than its predecessor, only two hours nineteen minutes. Like Dogville, von Trier treats the set like a play in a black box theater. The narrative consists of eight acts. Grace no longer seems like von Trier’s traditional women Christ like figures, but instead becomes Tom from Dogville, a leader who wants to create a world that reflects her ideals, but instead takes a path towards incompetence, turns democracy into tools of oppression and exploitation and revels in the stereotypes and dehumanizing fantasies that she claims to want to obliterate. It also would not be von Trier if he did not get to have a scene where Grace’s Mandigo fantasies turn on her, which I found distasteful, but am willing to hear arguments why my instinctual response is prudish. I saw Nymphomaniac so I am unwilling to be charitable on this topic when it comes to von Trier’s depiction of black men and white women having sex. It feels as if he has a prurient fascination with black men’s genitals mixed with a dash of his trademark sexual torture of women characters. Even consensual sex gets transformed into torture in his hands. He strains to make her father’s words at the beginning of the film prophetic. Grace never screamed during her incessant, multiple rapes at Dogville, but sex with a black man is an entirely different story.

I am one of the rare people who preferred Dogville to Manderlay, but I do not mistake that assessment for a complete dismissal of the latter. I feel ambiguous about this sequel. Manderlay uses slavery after abolition to tackle colonialism in the twentieth and twenty-first century. It is a thinly veiled criticism of American international invasions in places like Iraq, which is explicitly confirmed in the end credits when von Trier once again uses David Bowie’s The Young Americans, shows photographs of racism with a quick image of George W. Bush. It is von Trier’s most politically explicit film and least theological film. He punctures the delusions of the White Savior as ignorant and destructive, just as harmful as what came before. Intervention without knowledge is a different kind of tyranny not deserving of gratitude.

I vacillate between thinking that Manderlay’s denouement is profound and/or fundamentally derogatory. There are nice touches that von Trier uses to underlie Grace’s racism-her inability to distinguish black people as individuals, her use of blackface and her sexual harassment of those whom she claims to want to protect.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

The big twist is that the mistress of Manderlay was actually a captive figurehead, and the slaves used the disguise of slavery and discrimination after abolition as reparations to protect them from the racism of the rest of the world so they could create an imperfect society that most benefitted them. On one hand, there is some truth to this outlandish eleventh-hour twist. Enslaving another human being makes the perpetrator captive in another, different way, enslaved to a fiction that makes her a monster. Just turning recently freed people out of a plantation without the money and property still plagued with the attitudes that created their abuse is not really freedom. It is a provocative and clever idea to transform the very tools created to harm you into tools that will help you, but it also plays into the idea that racism and systems of oppression are simply products of a victim mentality, illusions and do not actually exist, and white guilt is not rooted in genuine wrongdoing. It perpetrates the myth that some people were sad when they were no longer slaves. It is offensive to imagine that anyone would willingly submit to such an institution, even as a cover story, in order to defeat racism. Even when it did happen in the real world, it did not last very long. People find it inherently galling to be seen as less than who they are. If human nature is inherently infected with original sin, an aspect of that sin is pride whether correctly rooted in inherent worth and dignity or a bloated sense of over importance.

I prefer when von Trier has a less specifically recognizable political agenda and is more broadly critical of humanity. By managing to avoid being a complete racist disaster, Manderlay feels like von Trier’s take on The Office if it was set in Jim Crow Alabama except not funny and still racist. The issue of race is already too potent a topic to effectively use as a metaphor for some other issue. I would not encourage anyone to watch it if you cannot handle cruelty to animals-a donkey got killed for a scene, which was cut, but was the horse on fire simulated or real? Only enthusiastic von Trier fans should watch this film otherwise a viewer will not get as much of a return on their investment.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.