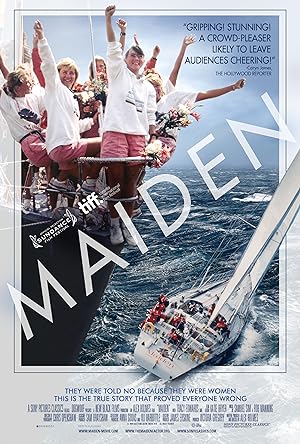

Maiden is a documentary about Tracy Edwards and how she assembled the first all women crew to compete in the Whitbread Around the World Challenge from September 2, 1989 through May 28, 1990. I am a sports atheist, but I’m amazed that I did not know about this story because I went to an all-girls school around the time. I’m still a sports atheist, but the power of the Internet compels me to know all about Megan Rapinoe and the US team’s victory in the Women’s World Cup Final. I do consider myself an armchair adventurer, especially regarding any stories related to the ocean, so the previews captured my attention immediately.

Maiden is the kind of documentary that you never want to end even when the ostensible mission statement has been achieved, and the race is over. Now armed with the knowledge that Edwards has written two books, Maiden and Living Every Second, maybe my curiosity can be satiated. Even though the majority of the documentary focuses on Edwards, it also interviews everyone on the crew, the journalists who covered them and some of their competitors. Even though you can find out whether or not Maiden won, I didn’t know going in, and I was literally at the proverbial edge of my seat wondering where they would rank so I would recommend that you keep yourself in suspense and don’t spoil the movie.

Maiden manages to make the viewer feel as if we are experiencing the race as it unfolds. The film is wonderfully edited and paced by intercutting between actual archival video, which there is plenty of, and interviews made for this film, but have the feel of a confessional. The competitive spirit of these racers has not flagged a bit over the years regardless of the gender of these sea lovers. There are several stories being juggled at once, but the storytelling is so seamless that you may not notice. You have Edwards life story as the overarching framework, which explains how she got interested in sailing and why she wanted to enter the race. You have the story of the race and the excitement and suspense of who was going to win. You have the individual stories of all the participants whether they are racers or journalists. You have the primal story of life on the ocean. You also have an older story that permeates each of these stories and existed before the start of the race and still continues long after the race was complete: sexism.

Sexism is a story that these women would rather not play a role in. They care more about racing. The men then and now (albeit somewhat sheepishly) admit that they rather enthusiastically and expertly adhered to their roles as chauvinists. One journalist from The Guardian thinks that he is giving Maiden’s team a compliment when he says, “They were heroines. Well, heroes. They were regarded as men at that point.” If you perform well enough as a woman, maybe you get to graduate to maleness, but you’re an exception, not an example of how women should generally be treated. If it were still up to them, they would not even have access to a path to achieve maleness and still be excluded.

There is another story that is explicitly a part of the story, but not as deeply explored and analyzed. There is the story of countries. These women are British sailors, but their nationality accords no benefits that a British male sailor may expect as a representative for his country with a huge naval history and reputation to protect until after the race ends. This naval history also intersects with imperialism. This race is just a shadow of the historical real race around the world that European countries engaged in to collect colonies and exploit them. While wealth is discussed, the source of that wealth is never examined. As an American viewer, you could be puzzled why the Belgiums are so good at this, but as a history lover, they were good at it then too. Just ask the Congo Republic.

One of the most taken for granted subversive acts in Maiden is how Edwards ultimately gets financing for her adventure. It is part happenstance, but also part of a broader tradition of (former) colonies treating British women better than they would normally expect to be treated in their homeland. As Letters from Baghdad quoted Gertrude Bell’s words, “I am a person.” Countries with reputations of being bad for their women in Western countries can swoop in and humiliate those Western countries by being more progressive and affluent than their former overlords. If it isn’t a deliberate, conscious act, it is a subconsciously subversive response to dominance and prejudice by using the energy of a system against itself. There is also a kind of subconscious solidarity between people who have had to exist under an empire without experiencing the full benefits as a member of that empire.

The reason that people fall so easily into these preordained roles of exclusion is because the entire sport rests on the unspoken rules of privilege for men, countries, ethnicities, skin color and wealth. This story is even bigger than sexism. The hate tree has many branches, and if sexism is involved, there are probably other elements. Edwards just wants to sail. She has the skill, but the skill is the last thing needed to enter the competition as insane as that sounds even with lives on the line depending on that skill to make it to the end of the race. She has the right nationality, but she is a woman and not wealthy. Any race using a yacht implicitly demands exclusion so while her astonishment, and ours, is understandable, it is also completely missing the point. To a certain degree, the point of this race is exclusion so she is violating the terms and conditions of the sport, and the reaction, though morally wrong and innately absurd considering its ostensible, explicit purpose, to sail around the world, actually makes sense if one considers the overall context of the race, which I actually know nothing about, but as a sports atheist, I feel as if I could look at a sport dispassionately and make associations that others can’t because they are so into the actual sport. They’re too close to it.

Maiden may not explicitly break down all the layers of the story in the way that I have, but it definitely touches on the role of how generational trauma, which in Edwards’ case stems from her mother’s life story, and environmental coping mechanisms such as alcohol and physical abuse carries over in unexpected ways during different contexts. The documentary definitely sees the overlap, but I’m not sure that as Edwards tells her story whether or not she realizes that at the time she was occasionally emulating behavior that she despised in others although her abuse of alcohol does not appear to have the same consequences on others as what she experienced.

Maiden is one of these uplifting documentaries that you want everyone to see so the viewers can leave inspired and hopefully be better people. So far it has taken the lead as the best documentary of 2019, but there is plenty of time left for it to be beat. I highly recommend that you see it with your whole family, especially the children.