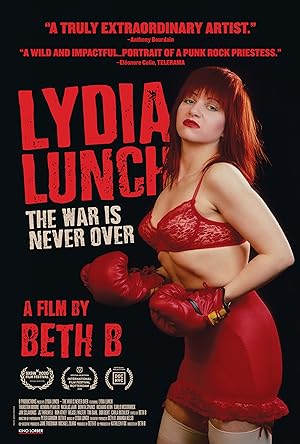

If you do not know Lydia Lunch, but want to become immersed in the life of a young woman who lived in Manhattan as a punk icon during the 1970s and 1980s and remains as irreverent and brash as she was then, check out “Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over” (2019), a one hour fifteen minute documentary. Lunch is still a singer/musician, spoken word artist—think stand-up comedian without a funny punch line to make the truth palatable, writer and actor as filmmaker; however this documentary is not for those with delicate sensibilities.

While I would have never watched “Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over” if it was not assigned to me to review, I do not regret that I did. I love learning about angry women and anything related to New York. Lunch and this type of documentary is very niche and not for the average viewer. Lunch has collaborated with Beth B, the director, before in dramas, but this film is their first documentary. Beth B’s documentary reflects the titular artist’s style as she wildly stitches together a retrospective of Lunch’s career in a willfully discordant fashion, but it is predominantly chronological so following along will not be a problem.

“Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over” intersperses montages of photographs, interviews with the artist and her contemporaries conducted specifically for this film, and archival footage of Lunch’s performances. Trigger warning: some of the archival footage is pornographic from her autobiographical collaborations with Richard Kern, another underground filmmaker. The sexual content of her films may be therapeutic for her, but triggering for viewers as she uses sexual trauma to become metaphorically homicidal, not suicidal, a way to get power and turn the tables to paraphrase her own words.

“Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over” would have been stronger if the film focused on the artist recalling her life and career since she is an amazing raconteur. Her discussion of trauma and going to extremes to discover her own definition of normal and survive was my entry point into the film. Because Lunch is political and sees herself as a product of her times, Lunch remains timeless. If a woman in her sixties can still rail against the hypocrisy of the industrial war complex dominated nation that seeks to outlaw abortion and it still is germane, either she is like a modern-day profane prophet and/or things never change. Lunch explains, “The sixties failed us,” which is as relatable as she gets.

Lunch’s outrage and anger are delicious, but “Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over” is really for those hard-core fans who will be thrilled to hear from other famous figures from the No Wave period cosigning Lunch’s artistry. If there is a major difference between neurotypicals and neurodivergents, neurotypicals derive value from validation so Lunch’s coolness is derived from the fact that so many people whom they deem cool like Lunch. I wanted to know if Lunch was cool on her own terms. Because the other people were equally unknown to me and not the topic of the documentary, they felt extraneous. Her value is innate, and she does not need external validation. Beth B is content to cater to the fan base and probably is not seeking to garner any new interest. Are they fine with being famous among a certain segment of society or oblivious to how most of the world is unaware of their existence?

This obliviousness among the No Wave crew is important if this documentary and Lunch’s work is placed in a broader context. Lunch discusses surviving sexual child abuse and sexually propositions/harasses men depending on your point of view. While “Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over” briefly shows the occasional awkward reception that Lunch receives from her male bandmates when she teases them, Lunch dismisses the idea that she could be wrong. The documentary has one scene where she compliments a black man in a sailor uniform with the name Slaughter. We do not know how he feels about this interaction, and the documentary does not care about intersectionality and power differentials. He may have loved it. He may have hated it but felt powerless to say anything because of a function of her age, gender, and skin color. If he offends her, the situation can get dangerous for him. Lunch is not a revolutionary in these scenarios. She is part of the status quo.

“Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over” cares what men think when they cosign Lunch, but does not dig further when they are silent and appear uncomfortable. It can be true that men brutalized Lunch, and because Lunch is the lead in her band, Retrovirus, her bandmates may act like her antics are acceptable and good-natured fun. It may be an organic dynamic that they enjoy, but to pretend that she is immune to accusations of wrongdoing because she is a woman misses the point. There is a lack of introspection and recognition that Lunch’s privilege permits her to commit acts without fear of reprisal, which many segments of society could not do. Their whiteness allows them to be anti-commercial and opt into marginalization when it suits them.

Lunch understands women can be perpetrators because in one scene, she calls out Hillary Clinton as a warmonger, which is interesting because the footage may have been shot after Clinton retired from public office and during Presidon’t’s term. If there is footage of Lunch critiquing Presidon’t, it is omitted, but the documentary fits in comfortably with progressives who save their biggest criticism for Democrats, but remain silent in the face of injustice from Republicans. I need that same energy and outrage. I would love for them to explore why they do not do it? If Clinton, a woman, can perpetuate an unjust system, then I would hope that Lunch would use her piercing intellect to examine how she promulgates an unjust system. Lunch understandably suffers from internalized misogyny. Because of the abuse that she endured, some of her act ridicules, but does not name Me Too and Times Up for not reacting to abuse similarly—by becoming aggressive sexual agents. She relates to her father’s lack of impulse control and blames her mother for his acts of incest, which may be the correct stance to take since she knows her life better than anyone else, but it is part of a pattern to create a false equivalency between men who commit crimes and women who are complicit or unaware. Is it revolutionary or reactionary to relate to the person with power and try to replicate that power to heal yourself?

If I sound critical about Lunch, it is out of curiosity because I do love her anger and her willingness to discuss herself and taboo subjects. While I do not think that I will watch another Beth B film, I would read one of Lunch’s autobiographies, including the book that accompanied this documentary. She also has a podcast, “The Lydian Spin,” so that could be intriguing. “What you call life, I call an incurable sexually transmitted disease.”