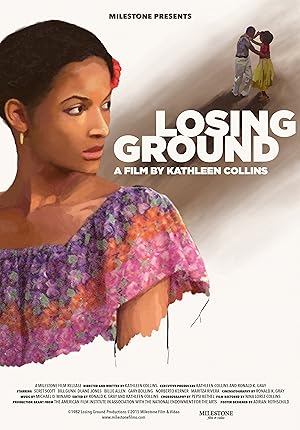

“Losing Ground” (1982) is the first feature film that a black woman, Kathleen Collins, directed, since the 1920s. Professor Sara Rogers (Seret Scott) teaches philosophy and plans to spend the summer researching ecstatic experiences. When her husband, Victor (Bill Gunn), a painter, sells one of his abstract paintings to a museum’s permanent collection, without consulting her or considering her needs, he decides to rent a house in upstate New York, and starts to pursue new artistic visions by no longer working in abstract and depicting the world around him, which leads him to flirting with other women, including his dancing muse, Celia (Maritza Rivera). Sara tries to adjust to the challenges of the new environment but gives up in frustration and accepts a film student’s offer to play a jealous, tragic mulatto in his senior project film, a silent adaptation of the folk song, “Frankie and Johnny.” She has chemistry with her costar, Duke Richards

(Duane Jones). The denouement unfolds with all the characters spending twenty-four hours together in the upstate home, and the filming of the last scene in the film.

On February 26, 2023, I had an opportunity to attend an “Artist Housing Talk with Seret Scott” followed soon thereafter by a showing of “Losing Ground” at the Harvard Film Archive. It was the ideal way of seeing the film. Scott, a civil rights activist and good friend of the deceased Collins, read excerpts from her journal, and Jerome Offord Jr., the Associate University Librarian for Antiracism, moderated the Q&A. Haden Guest, Director of the Harvard Film Archive, and Brian Meacham, the Film Archivist at the Yale Film Archive, moderated the screening, which was the first showing outside of Yale! It cost nothing except time, and it was time well spent. HFA is my old stomping grounds, and I do not remember the last time that I saw a film there.

Why did “Losing Ground” bring me back to HFA? The protagonist is a black woman nerd! A black woman wrote and directed it. Duane Jones is my all-time horror actor fave from George Romero’s “Night of the Living Dead” (1968) and “Ganja & Hess” (1973), in which Bill Gunn played a supporting role. The film is set in New York and hearing Scott speak made me cut my workday short. As I watched the film, I did not relate to the protagonist, but Scott stating that these characters were in stark contrast to the iconic blaxploitation characters of that era helped me appreciate the independent film more and understand why it did not gain traction until years after it was released.

The camera movement, composition, and diegetic sound in “Losing Ground” tell the story without prose. Pay attention to how the camera moves. If it is panning from side to side, Collins is showing the relational and literal distance between characters. If characters share the same frame and are on the same level, it reflects unity. Collins imbued every moment with significance. The closeness of the camera to the subject(s) depicts the viewers’ relationship with the subject(s)-are they distant, warm, relatable, alone. The objects in the same frame as the characters are visual psychological profiles of the characters.

When Collins introduces Sara, the camera focuses on one student’s face then pans backward to reveal a packed classroom, and the students’ varied reactions reflect how they receive her lesson. The shot of Sara as she lectures could be from the perspective of a student sitting in one of the middle rows of the classroom. She is remote, closed off and academic. The classroom is uniform, rigid, functional, monotone though bright in patches with yellow and blue. In contrast, Victor is in an open, muted but colorful space, alone until Sara comes home. The camera pans from left to right to show the distance between them, but eventually they share the same frame, and the camera becomes a medium shot. When the camera takes his side, by shooting over his shoulder, he looks down at her. When the position is reversed, she looks up even though he asks her to ascend a moving ladder and be on the same level as him. Meanwhile the radio has a man droning in the background about the artist as if we are hearing Victor’s thoughts, “No demand can be considered appropriate of him.” He dominates the home, and there is barely any space for her. Her needs are not germane.

If you are a fan of philosophy, “Losing Ground” is for you. Turn on your closed captioning to ensure that you will not miss a word. The opening classroom scene may not seem as if it is establishing the underlying themes of the story, but it is—one of my favorite tropes, the foreshadowing lecture. Sara is lecturing about existentialism, which asserts that an absurd universe or human existence is a “reaction to the consequence of war. The natural order, if there is such a thing, has been violated. Chaos exists, not as a mental possibility, but as a physical and emotional fact.” Sara jokes that Jean Paul Sartre’s “No Exit” exists in hell, “They must endure each other’s company without relief or privacy.” After class, a student discusses Genet, whom I am unfamiliar with, the concept of the outsider and exclusion, “a society can impose group definitions that an individual is powerless against.” Her work reflects that the natural order, their marriage, is in chaos, and regardless of intention, Victor has put her under siege. He invades space through movement and sound.

In an early conversation with her mother, Sara reveals that Victor hates parties, but does not mind trios. In a scene preceding the denouement, there is a personal adaptation of “No Exit” when Victor invites too many people, Carlos (Noberto Kerner), Victor’s friend and mentor, and Celia, to be spectators. They are not actively trying to do so, but Victor is inviting them into their home without consulting her because it is his home, not his and Sara’s, which is why when Sara does it, he is enraged.

Victor and to a certain degree, Sara’s mother have assigned an outsider identity upon Sara that feels too limiting and in exile from “magic” or “ecstasy” as an academic in relationship with artists. George (Gary Bolling), the film student, sees what a smoke show she is, how she is artistic and capable of ecstasy, which her family does not. She is the utter stereotype of the nerd who is a hottie once she takes off her glasses and exchanges her hot librarian aesthetic for a sexier disco vibe where she literally lets her hair down. The film gives her an opportunity to express feelings that Victor shuts down when she expresses them in her personal life.

“Losing Ground” is an emotional journey about how a married couple begins to take diverging, individual paths. The first rift occurs after Victor comes home from a solo trip to the upstate neighborhood, and his interest in exploring a new way of painting seems inseparable from his womanizing. Later after the “No Exit” party, Sara parallels his phallus with a paintbrush. He puts his charcoal sketches on the wall and responds in monosyllables to her questions. Most of the sketches are of Victorian houses. He assumes that Sara will bear the burden for his vision and commute to the city for her work, research in a library, which infuriates Sara. She exits the frame. Collins cuts, and the scene resumes in their bedroom. When Collins shows the bedroom in an earlier scene from one side, grey canvases dominate the composition. In this scene, Collins shows the other side, windows overlooking an urban skyline on either side of an oval mirror, much like George’s monocle, on a sliver of wall and plants line the wall. This space represents Sara’s space in the home. It is a sliver of city, tamed plant life and a reflective surface to see herself. Sara looks in the mirror—remember her vision of hell based on “No Exit” is a place with no windows or mirrors so we are seeing her heaven.

Sara asks Victor, who follows her into the bedroom—once she stops trying to divert his attention from his work, he is interested, “If I did something more artistic like write or act, would that get me a little more consideration?” Victor replies, “If you were any good.” “Nothing I do leads to ecstasy.” In a later scene with her mom, she reveals that his artistic ecstasy feels like cheating. He enters the frame only to turn his back to her, thus missing that she unbuttoned her shirt and is flirting. Instead of admiring her, as all the students do, he just makes a Freudian suggestion that she is trying to be her mother then dismisses her concerns as a mulatto crisis. He literally does not see her and asserts the dominance of her needs over hers. In their bedroom, he is a man baby—in the first bedroom scene, jumping on the bed and messing up her papers and in the second bedroom scene, complaining that he is hungry and cursing. (Um, dude whose fault is it that you had two espressos all day? Feed yourself.)

This second bedroom scene is the first time that the tragic mulatto storyline is introduced. In this case, mulatto refers to a light skinned black person, which Sara is. The film student also has Sara play a homicidal, tragic mulatto in a vaudeville show. I always thought the tragic mulatto trope was about not fitting in with white or black people and must confess that I am uncertain what Collins meant and regret not asking Scott about it. Mulatto here may be a woman that sits on the line of intellectual and artistic/emotional or between two lovers, her own or her chosen partner. In the scene after the second bedroom scene, Collins introduces a real man, Duke, who can engage with her in philosophy or as a performer. Duke wears a hat and a cape inside, which makes him seems mysterious. His speech about himself makes him seem pagan or fallen since he was going to become a minister. Capes make me think of vampires, Dracula specifically, but “Losing Ground” is not a horror movie. He literally makes her forget about her family and the dinner to celebrate the painting sale.

The family dinner is strange because my first impression was that Sara’s mother was flirting with Victor. Like Victor, Sara’s mother offers backhanded comments to her about not having children, minimizing her work and criticizes her looks after Sara refuses to write a play about her. I rethink the latter as possibly concern based on subsequent mother-daughter scenes without Victor. By the end of that scene, the camera shifts from focusing on mother, pulling back to only frame the mother and Victor, then pulls back further to reveal where Sara is. The mother sits in between the couple as they are clustered at the head of the table. Then the camera moves forward and gradually pans to only focus on Sara until it moves into a closeup to reveal Sara’s ambivalence and disappointment in the interaction. The camera movement represents the family dynamic. Sara is on the outside and alone.

Sara’s initial time in upstate takes on a mystical quality and reminded me of approaching Dracula’s castle since it starts with a verdant hillside before panning down to reveal a quotidian highway with cars and construction barriers, but Collins does not show us the couple, only permits us to hear their conversation about her dream of approaching a castle. When they go to the upstate rental home, the way that they share the same frame and space is promising, intimate, warm. At this point, Sara’s wardrobe becomes more feminine and reveals more skin. The rental is warm and has earthy tones. He sees her and carries through with his promise to paint her, but this warmth does not last for more than an evening, and even then, he delivers underhanded compliments.

A few scenes between the day and night scene at the rental shows Victor visiting Carlos at his studio and reveals their different styles. Carlos’ canvases are smaller, committed to exploring color, form and space. Victor considers abstract art pure and decides to embrace telling stories through his art. Carlos sits slightly above Victor. When the couple pack up to prepare for the move, Victor declares Carlos’ influence over his work over and maybe his life. He is like an adolescent declaring his independence from his father, which unfortunately for Sara, turns Sara into his mother.

Collins parallels Sara and Victor’s workdays while they rent the upstate home. He goes into the country, and she goes to the library. They are trying to make it work. When they reunite in the evening, his assessment of her as “beautiful” in the day morphs into “cold, analytical” by night. “Are you pretty or is it just the light?” It is at this moment that Sara begins using vernacular and makes threatening jokes. Collins links painting with sex in this sequence.

The second parallel illustrates why ultimately the couple will not make their time upstate work. He plunges into a populated waterside area where Celia dances, and he throws away his sketching pad to join her. Meanwhile Sara is alone in the house talking about gods and spirits possessing people; how the possessed person is unconscious then reaches ecstasy after possession is over. Her surroundings are dark with wooden sculptures of monks. Unsatisfied with the theoretical, Sara visits a psychic in a lush, verdant backyard, but the women are not connecting. Sara wants the psychic to explain how she feels when she has visions, but the psychic just tells her future in filmmaking. Sara leaves puzzled and disappointed, “What am I looking for?” She enters a church and kneels at an altar. When she and Victor are back together, she throws away her book in frustration, and Victor looks puzzled silently beside her as if she is babbling nonsense. It is another opportunity for intimacy, but he does not engage as she does with his epiphanies. She feels exiled from ecstasy because she cannot find it as a gypsy or in a church.

The third parallel shows him wandering the neighborhood to look for Celia then brings her home to paint her portrait. Meanwhile Sara gets a call from George to act, which she refuses. The scenes with Sara, Celia and George are so awkward and polite. Initially he stands between them. Collins shows Sara’s reaction as she watches George and how he interacts with Celia. George is basically holding the women hostage to listen to his stories. By dinner, when the couple is alone again, the camera is panning back and forth, and they do not share a frame again until the last part of the film. All these scenes have microaggressions directed at Celia.

The fourth parallel drives Sara off the property as music from their painting session drives Sara. Once again, there is no space for her, and Collins cuts to George at the filming location back in the city. George uses his monocle to frame Sara-first in her office then in this scene. It is like the mirror. He sees her. Acting becomes an act of possession. Sara finds her ecstasy by following George’s direction. When she arrives at the location, she sees Duke in the distance, but when she looks away, he disappears and reappears beside her as if he is a supernatural figure. I love that we never see Vicky, the costume designer, whom George is always shouting for. George’s film is about a vaudeville couple that a woman, the character Nelly Bly (the voluptuous Michelle Mais), gets in between, and when Nelly dances with her man, Sara’s character kills him. Once Victor realizes that Sara has left, he reacts like a spoiled child and accuses her of being angry at him or mad in the sense of crazy. (Why would she be angry at you, Victor? Did you do something wrong? He is so close to getting it.) Why is she crazy for exploring something different if he is not. Victor is a fan of the double standard.

The film within a film is like the play in Hamlet except Sara’s emotions around Victor’s unfaithfulness are interpreted literally as violence. George’s film gives Sara a safe way to explore what Victor has been doing: dancing with others and having at least an emotional affair. Meanwhile Victor is entertaining Celia in his home and puts the moves on her. Rivera’s acting is transcendent, and she makes us believe that Celia is better than he deserves. She has a wistful expression when thinking of Puerto Rico. The next day, Sara, Duke and Nelly shoot a dueling dance scene. The dialogue reveals that Sara also had time to write her paper. Sara is her full self. By the evening, Sara is dodging Victor’s calls, and Victor wants her home. The subsequent shoot echoes Victor’s musing on abstract art as Sara theorizes that the purpose of the scene has “something to do with the relationship between the characters, the space, the light,” which shows that she has exchanged the abstract nature of academia for literal representation in film, a similar professional journey as Victor. It is interesting that the couple are on the same road, but it destroys the relationship. The scene ends with them assenting to the director’s surprise instruction for an onscreen kiss after she notes that her husband is middle-aged.

The next scene complements the earlier scene with Carlos and Victor except Carlos is visiting and appreciating Victor’s work. Victor describes himself as 25, which is generous. “I’m vulgar, deceptive and I’m full of dirty tricks.” So Victor is having a midlife crisis. At least he is self-aware. Carlos is interested in the subject inside his mind, and Victor is interested in nature but is looking at Celia.

Collins makes the last fifteen minutes a payoff for everything set up earlier. It showcases the actors’ talents, the individual characters and relationship dynamics. It is also a perfect preparation for the denouement. Victor, who hates parties but doesn’t mind trios, discovers that he hates it when men outnumber the women. Carlos and Celia speak in Spanish, which makes Victor boorish and interrupt their conversation, but Carlos chides him as only an old friend could, and Victor takes it well. He brightens at the sound of Sara’s voice until he turns around and sees her walking in with Duke, which stuns Victor silent, and his eyes bug out of his head. Celia and Carlos see Sara walk in before Victor does, and they look serious and inquisitive. Celia later looks interested. As Victor advances on Duke, who towers above him, Carlos puts himself in between the two men. For once, Duke is dressed for a weekend in the country, not in a black cape and hat. His mystery has evaporated with contact. Victor feels threatened and is jealous. Stay mad! By being left out, he finally feels how Sara felt. Sara announces it is a party, which we know, and soon will see why Victor hates them.

The subsequent scene unfolds at night in the dark. Celia and Carlos and Duke and Sara are dancing together, but Victor breaks them up and makes himself the center of attention while expressing some bias about Celia and Carlos’ Latin heritage. He bounces between Celia, who rejects him, then Sara, who relents, but he insults her, “I forget you can’t dance.” Duke, an actor and a keen observer of human behavior, is taking in Victor’s spectacle and is scratching his head while Victor resumes his interruption of Carlos and Celia. Carlos is no longer a gentle admonisher and understanding friend, but confronts him. Celia’s solo dance during this confrontation is reminiscent of the first time that they met, and she rejects his attempt to control them. Duke responds to her speech with admiration with his back to Victor, and Victor is hostile so Carlos puts himself between the men. Duke tries to stop Victor’s ridicule of Carlos and Celia’s accent and his mockery of their moves. Sara is at the edge humiliated and silent. Once Duke resumes praising a receptive Celia, Sara takes centerstage, and serious Victor starts ridiculing Sara for associating with Duke and how incongruous it is with her love of philosophy. With everyone else, he plays a hostile buffoon, but he is serious with her with no veneer of jocularity. He is intimidating, and out of context, I would believe that he was going to punish her later and is a physically abusive husband. He tries to make eye contact with her, and she can barely look at him. He proposes that they sleep under the stars, and in the oddest juxtaposition, the next scene shows all of them in sleeping bags by the pool. Worst sleepover ever! The sleeping order is Duke, Sara, Victor, Carlos and Celia.

Victor’s annoying antics resume when he wakes up everyone else by loudly declaring a swim. I would hate him forever. Carlos and Celia have clearly forgotten the prior night and join him. Sara and Victor are against it so Sara seizes on any opportunity to avoid swimming and runs inside to get clothes for Celia who leaves the pool first because she is too cold. Duke jumps in afterwards. Celia seeks refuge in the sleeping bag. Victor jumps on Celia, who protests in English and Spanish. Celia is fascinating because she had at least an attraction and a fling with Victor, but after witnessing his behavior with Carlos, she rejects him. Sara comes out and finally loses her shit. Victor shouts back, “This is not one of your classes. Don’t lecture to me.” She bellows, “Don’t fuck around then!” It is a long overdue moment of anger, and Victor finally shuts up.

The next time that Victor sees Sara, he walks in to see Duke, Nelly and Sara act the final murder scene in George’s movie. For once, Victor does not make noise or try to be the center of attention because he is respectful of the creative process. As he watches Sara shoot Duke for dancing with Nelly, he finally realizes the impact that his behavior had on Sara and appears contrite. He said that he would give her consideration if she was good so she must be because he finally appears contrite and understands the impact his selfish actions had on Sara and their marriage.

Even though I primarily focus on Sara and Victor, the other characters are substantial characters. In a parallel world, I love the idea of Collins living long enough to give these characters their own movies. Unlike Sara, Celia has a lower threshold for tolerating Victor’s antics. I understand the initial appeal of taking Victor up on his offer, but I am surprised that she entertained his advances as long as she did. I also do not understand why Carlos is friends with him. Victor is biased and insulting. It does not make sense to me that their respective relationships can survive the weekend except for Carlos’ innate graciousness and shared history.

Duke is inscrutable and chameleonlike. I found it interesting how he changed his demeanor and behavior. With Sara, he engaged her intellectually and agreed with her sentiment, but when she is absent, he is as playful and chaotic as the others. While Victor mocks Carlos and Celia’s accents and moves, Victor adapts to them as if they were in a jazz band. He follows their frequency, but left to his own devices, his initial physical response is discomfort. He signed up for a weekend upstate with a coworker. The nature of his life is fluid, and the relationship only needs to last until the film wraps though he has a more sincere, organic connection with each character than Victor can ever hope to have, including with Sara.

Each of them seems more satisfied with their sense of self compared to Sara and Victor, but permeable enough to get swept in the wake of their crisis without opting out. Scott shared that Collins had an altar to her own soul and was interested in discovering herself through film with Scott as her onscreen proxy. The horror elements are not supernatural, but the unknown within.