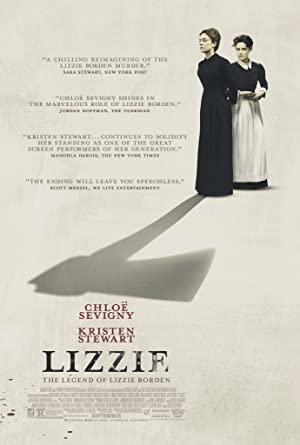

Lizzie stars Chloe Sevigny as the titular character, Lizzie Borden, who is famous for being the chief suspect in the murder of her father and stepmother. This movie is the latest exploration into life before the murder and the subsequent proceedings. It is not a bad movie, but it isn’t a great one. It is simply a restrained sampling of all the notable touchstones that could have contributed to this historic double homicide.

It appears as if Lizzie Borden has a number of independent actor queens as fans. I indulged in the anachronistic fun of Christina Ricci’s series (skip the movie), which reveled in her naughtiness. Sevigny’s Lizzie is more severe and sardonic, rooted in plausible reality and the restraint of its era. It also features a buffet of vignettes, which though not isolated from each other and quite comprehensive in painting the image of an unhappy household, these scenes do not add up to a cohesive portrait though they reflect the complexity of the main character. The movie introduces then abruptly drops elements as it unfolds. A catty exchange at the theater comes out of the blue, but is it a specific disdain for her or the family, regular or out of the ordinary? Lizzie is often ill in the first half of the movie, but not the second. Certainly this illness is a helpful way to make Lizzie draw closer to certain characters, but that was going to happen anyway based on early scenes of interaction. Is it a psychosomatic illness expressed from repression, a genuine malady, neither or both, a contributing factor in the crime to suggest madness? I actually don’t think that it was any of those things just to show that she often got ill, but if she often suffered from seizures, why does it suddenly stop? It seems as if it is just another explanation why her father makes certain decisions about her future, but her older sister will also have to endure the consequences of these decisions so it seems extraneous in retrospect.

Generally a house has a routine and rhythm that gradually adjusts and accommodates any new elements until they are also incorporated into prosaic life. I never really felt as if the household was a single, dysfunctional organism even though it is strongly implied. Kristen Stewart plays Bridget Sullivan, the Borden’s housekeeper, whom most people call Maggie because she is so low on the totem pole that she doesn’t get her real name. Stewart does a great job with the accent, but because every time that I see her in a movie, she is trembling, hesitant and reluctant to make eye contact, I have no idea if she is actually good or not. Reviewers are generally gaga over her, but I don’t get it, and maybe it is my fault, not hers, because I just think Twilight whenever I see her or Robert Pattinson. As the newcomer, the film vacillates between predominantly seeing things through her eyes and Lizzie, but also the patriarch, played by Jamey Sheridan.

Lizzie’s cast is filled with really great actors. Sheridan can either be everyone’s favorite supervisor in Law & Order: Criminal Intent or Randall Flag in The Stand. He does a good job of being reserved when you don’t expect him to be and not when you do. Scandal’s Jeff Perry plays the family lawyer. Fear the Walking Dead’s Kim Dickens plays Emma, the older sister. Perry and Dickens are given nothing to do, which is forgivable for any character who is not a member of the family, but inexplicable for a character who is.

The central problem of this film is that it is divided in focus. For me, it fails as a portrait of two women who come from different circumstances, but are bound by love and oppression. Lizzie is at its strongest when Sevigny is in a battle of wills, especially when she faces off with Denis O’Hare, who always gives memorable performances, but I’ll always think of him as the terrifying Russell Edgington in HBO’s True Blood. O’Hare plays her rapey uncle and possible future guardian and elicited the only laugh from me when he whispers under his breath in frustration, “Fucking bitches.” There is a better movie in there, but it isn’t on screen.

These independent movie actor queens are attracted to playing this character because none of them doubt that Lizzie Borden did it, and they see her as a revolutionary. They empathize with her for acting against the gender norms of the time and revolting against the patriarchy. While turning it into a coming of age, lesbian gauzy romance and sexual awakening is a worthy focus, if we’re honest, we’re here for the murder. The rhyme is about a particular kind of whack, and it is not supposed to be the pretty, pleasurable kind. When Lizzie gives us gruesome scenes and signs of stony resolve, the movie not only comes to life, but it is quotable.

“Men don’t have to know things, Bridget. Women do.” At times, she acts childish and impulsively out of frustration. Then she screws up her courage and seems unruffled only to give way to fear in one of her many showdowns. When she finally has impenetrable confidence brought by experience and moves near an exit, you realize that a movement that seems casual could actually be a trap and ask who is actually trapped in prison alone with their enemy. It could have been a movie in which all the women individually, but separately, show nothing but contempt for the status quo in subtle ways, which is teased out in an electric scene between Sheridan and Fiona Shaw, who plays the step-mother, but are so trapped in their particular set of specific socioeconomic shackles that they never gel. Shaw and Sevigny depict that dynamic, but because the sister is largely missing from the equation, it is not as dominant as it should have been.

I do think that Lizzie was right to suggest that part of the lead’s motivation stemmed from wanting to be with her love, but the servant master relationship is always problematic regardless of whether or not it is heterosexual or homosexual because of the inherent inequitable power dynamic at its inception. I wish that Lizzie’s creators had seen William Oldroyd’s Lady Macbeth, which is a perfect movie, that shows how oppressive structures negatively effect everyone in different ways, but also benefit some in different ways depending on race, gender, economic status, etc. Lizzie and her father may not be treating Bridget in the same way, and Bridget may consent to Lizzie, but the fact that neither respects the boundaries of her space from the beginning and expect more than the services that they ostensibly hired her to perform for them is a similar privilege that Bridget cannot demand from them if she wanted to be the one to engage in a personal relationship with them. The Bridget that we see at the end of the movie who awakens to the reality of her station is the Bridget that I wanted to see throughout the movie—a woman skeptical of kindness and love because of who is promising it. A woman like her does not travel half way around the world and leave everything that she knows and loves just to be swept away by romance without some level of skepticism.

If you are interested in the story or are a fan of the cast, definitely see it, but don’t expect to be blown away. I lost my suspension of disbelief fairly early when it cut to six months earlier than the opening scene, which would be February in Fall River, Massachusetts, which would not be a time of golden hues, but harsh cold. If Lizzie can’t get that detail right and are determined to lull us in with lighting that the filmmakers think matches the tone of the story that they want to tell and not the reality, then I can’t trust them on the big picture.