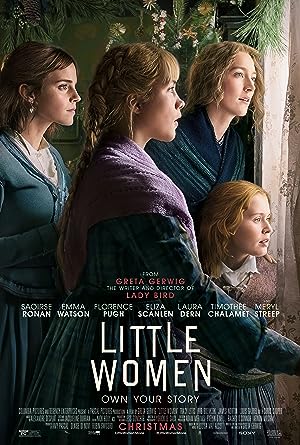

I have been a fan of Louisa May Alcott, specifically Little Women, since I was a kid. I even got some light ribbing in high school for still unashamedly adoring it. I have not read it in decades, but I kept the flame alive. I believe that I have seen every cinematic adaptation. I even saw the 1994 version starring Winona Ryder in theaters in Denmark to get a taste of home. I visited Alcott’s home. I have also been a Greta Gerwig fan since she was toiling in the mumblecore fields so naturally I was eager to see her take on the beloved American classic.

Little Women is Gerwig’s first adaptation, first period piece and first time not telling a story chronologically. The latter is the defining feature that distinguishes this film from earlier adaptations. Gerwig manages, like the onscreen publisher, to take the book apart and reassemble it in thematic order with Jo’s career bookends as the binding cover that ties it all together. The narrative has intersecting lines of the past and present, comparing and contrasting visually and tonally the warmth and optimism of childhood with the chill and melancholy of adulthood converging on the death of opportunities and loved ones. The unspoken question is how does one continue to recover and live well after such loss?

While Little Women may be my least favorite Gerwig film to date, it is still a solid, masterful adaptation worth admiring. It is my least favorite version because it was a mistake to explicitly state the amount of time between the intersecting storylines, seven years. While the cast does a superb job of shifting their physical demeanor and speech to convincingly play younger and older versions of themselves, knowing that the time was actually seven years bugged me. I am too familiar with each of these actors, except for Eliza Scanlen, who plays Beth, to think of them as children or younger than they are. I do not think that the average person will have a similar problem. Also Gerwig, whom I adore for embracing her characters’ flaws and loving them anyway just as she did in Lady Bird, really opened my eyes to the March sisters’ flaws, and I was not ready for that. I think that I have been downplaying some of their antics because I know what happens—that no real lasting damage was done, but in this film, the impact of every decision felt critical. So I do not really have a problem with the movie per se, but I am not prepared to free my imagination and carefully examine these characters as people. I am not ready to let go. I may have to revisit the novel and movie or maybe just accept that for once, I cannot just be open to someone else’s vision. No disrespect intended, but I also cannot buy Bob Odenkirk as Father March.

I have noticed that in these perilous times, filmmakers are drawn to making films that explicitly address the problem of evil and how to fight it. Gerwig’s Little Women is the most woke film adaptation of Alcott’s novel yet. Gerwig does not offer any explicit answers or even judges her character’s decisions, but shows a variety of ways that characters live up to, compromise and neglect their ideals, which shows a lot of sympathy, love and understanding. She makes the Civil War explicitly about slavery, made it clear that the Marches were down with black people, references hostility to immigrants, the quotidian suffering of poverty and the endemic patriarchal structure which puts women at a disadvantage to men without feeling like an afterschool special or too preachy. The casting of Laura Dern, whose earlier role in Trial by Fire seems like a twenty-first century real life version of Marmee, is a brilliant first step to moving this film into an explicit socioeconomic and racial context. Gerwig’s intersectional commentary may be understated, but for her, it was screaming from her lungs, which made me proud of her. She is angry at the state of the nation.

Little Women’s underlying mood is anger at the constant systematic and personal unfairness of life. Gerwig seems to suggest that the reason that we try to do better for others is not only love, but anger at people not doing better whether it is Amy’s fury at Laurie or Laurie’s criticism of Meg. Honestly Marmee and Amy kind of upstaged Jo, whom I always related to in the past, and I wanted to see more of them. Even Beth has a moment of frustration at her sisters’ neglect of their mother’s (and God’s) admonishment to love their neighbors. The role of God in Gerwig’s films has practically been silent, if not almost invisible, in her prior films, but the one scene that haunts me is a long shot with the neighboring church in the background on Christmas Day as the entire neighborhood converges on the church, but the March women move left to be the church and help their neighbor. We never see the Marches in church because they are the church. Christmas is a way of life, not a holiday, a service, a meal or a present. It was a brilliant marketing move and a sacred visual sermon for Gerwig to deliver this film on Christmas Day.

Gerwig’s Little Women is also as dynamic as her other films, Frances Ha and Lady Bird. She prefers for her camera to move with her characters, especially at the beginning of her films, and her camera tracks right alongside them. This camera movement betrays her barely suppressible exuberance, energy and joy so while her work has always had a sense of mortality, there is a seasonal sense that spring is always bubbling underneath the surface, a new beginning. Gerwig’s films usually end with her protagonist finally achieving a career goal, but is alone; however she consciously chose a work that also ends with her protagonist surrounded by people that she loves and success. Gerwig’s work always feels semi-autobiographical so I am happy that she found her way of having it all instead of being in or feeling as if she is in semi-exile from her loved ones.

Gerwig’s Little Women is suitable for all audiences and is a great film for this holiday season. While it may not be my favorite Little Women (I did not cry), it may still be the best one in the way that it feels as if the March women are living, breathing human beings whom we could imagine meeting in the street.

Side notes: shout out to Abby Quinn, who has a blink and you will miss it scene. I would bet money that she is the next great amazing American actor, especially after seeing her in Landline and After the Wedding. Also Florence Pugh apparently owns the world because she has been killing it since Lady Macbeth. I recognized her Midsommar grimace on display in a couple of scenes. Chris Cooper, get money with this film and A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood. Enjoy your reunion with Meryl Streep. Also I do want to visit the parallel universe in which Sarah Polley writes and directs this film since I loved her documentary, Stories We Tell. I want to have my cake and eat it too.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.