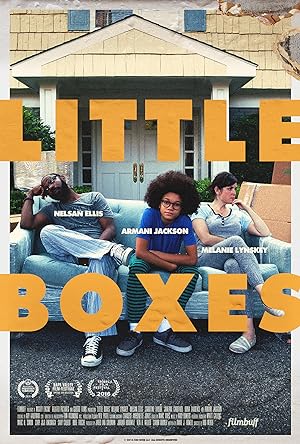

I was really looking forward to watching Little Boxes. It examines a biracial family’s move from Brooklyn, New York to Rome, Washington. I found this scenario incredibly relatable and thought the introductory tonal framing of the move like a horror story was brilliant because when you are a New Yorker, the idea of leaving your home town is a moment of dread. I am biracial and the move from Manhattan felt like a huge transition, especially discovering that even though Manhattan reflects the world, most of the world is not like Manhattan. I adore the dearly departed Nelsen Ellis and Melanie Lynskey, who play the married couple. Unfortunately it was one of two movies, the first was Hunter Gatherer, that I watched in 2019 with white filmmakers that felt as if my worst fears about Matt Damon’s casual comments came to life, “When we’re talking about diversity, you do it in the casting of the film, not in the casting of the show [behind the camera].” A man directed it, and a woman wrote it. In spite of having prominent black actors in the lead, ultimately felt like a let down and made me feel reluctant to see another film with a similar demographic even though there are great films with black protagonists with white filmmakers: The Color Purple and The Last Black Man in San Francisco.

Little Boxes is initially promising when it shows the family as a unit then how they fracture in different parts once they arrive at the new location because of their different experiences. Each member individually stumbles while trying to fit in then begins to gradually break the family’s social contract and lash out at perceived though not intentional slights when each feels alone. Soon each member gradually acts out in increasingly socially unacceptable ways, which while uncomfortable to watch, also felt organic, but I had a problem with the son’s story, which felt literally ripped off from Me and You and Everyone We Know, a movie that I hated because it clumsily handled intersecting issues of sex and race and performative gender norms.

Little Boxes definitely depicted the scenario in a way that was not as tone deaf as Me and You and Everyone We Know. It actually did a great job in making it seem like innocent experimentation as opposed to a huge leap for their age group, and the film could have still stuck the landing if it continued in the same vein that it had prior to that incident. Throughout the entire film prior to that incident, the filmmakers definitely excelled at depicting the black members of the family facing unintentional, well meaning microaggressions. The son is too young to entirely pick up on those cues, but the father registers each one even as he begins to warily find his place within the community; however in the denouement, by ultimately making the black father incorrect when he explicitly accuses someone of being racist, it retroactively reframes the story into making the black members of the family seem overly sensitive, aggressive and wrong and centers the white mother of the family as if she is reasonable, genuine and alone as a woman and the only white person in the home. I actually like the idea of the outsider not being racist and genuinely concerned about their son’s behavior, but my problem is with the film not continuing to show how each member of the family in that situation is simultaneously wrong and right.

Little Boxes’ denouement reminded me in many ways of The Help because of the way that the denouement was structured. It depicts black people actually doing all the things that other people accuse of us of doing who do not claim to be our allies. The story is a safe way for white allies to agree with the opposition and express those same frustrations with black people without risking rebuke because it is coming from the mouth of a family member. It is a sneaky way of centralizing white feelings and further delegitimizing black pain. I would have preferred if the story was always told from her point of view so this eleventh hour flip would not be so jarring. I actually think that it would be an edifying experience to commit to exploring how a white person feels like as a minority in his or her home who is sensitive to white supremacy while simultaneously understanding that the power dynamics outside of the home are completely different. It sounds as if you can never win if you look at it from that point of view, but in this case, it feels as if it is at the expense of the other two characters. Up to that point, all three members of the family are flawed, not entirely wrong or right, but to wait until the end to have one clear moment as a group that one person is unequivocally right and leads the way for the family to fall in line behind her felt as if the movie’s true sympathies were finally revealed.

Little Boxes actually had multiple scenes in which white woman are equated with the voice of reason that shocks different members of the family into course correction. I already mentioned two scenes when a parent complains about the son, and afterwards when the mother of the family advises caution before taking sides. Neither of these scenes on their own is unreasonable. The initial one that made me suspicious is when the mother hangs out with her coworkers who encourage her to engage in a specific behavior then chide her for following their advice too assiduously. Even though they were not wrong, because they caused that behavior, this scene really rubbed me the wrong way. Even when they are complicit, they get to be heroes, and that message is not counter cultural or thought provoking. It is what makes fifty-two percent frequently engage in damaging behavior while simultaneously getting to call themselves feminist without having to tangle with the complexity of their humanity and really facing accountability as the rest of us have to do. They get the credit without actually doing the work.

Little Boxes did a great job of dealing with class and education, but it felt a little rushed when it was addressed though it is perfectly represented in the way that the son adjusts his tastes and habits to fit in with the kids in the neighborhood. The regional and cultural differences speak to class as well. When the cousin visits, and he is clearly brought up in a more traditionally black way-religious, respectful, less rebellious, it speaks to the complexities of how race, education and class do not fall in clear lines.

Little Boxes’ ending felt abrupt, and even though the characters reassure each other of the state of the union, I was not entirely convinced that we were witnessing a rough patch in an otherwise uneventful road. The problems seemed serious, and by rushing through it, the reconciliation felt more like the eye of the storm, especially since they never really understood then resolved the real reasons why they were so easily divided initially. I know that others genuinely did not feel the same way and bought how the movie wanted us to leave, but I could not.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.