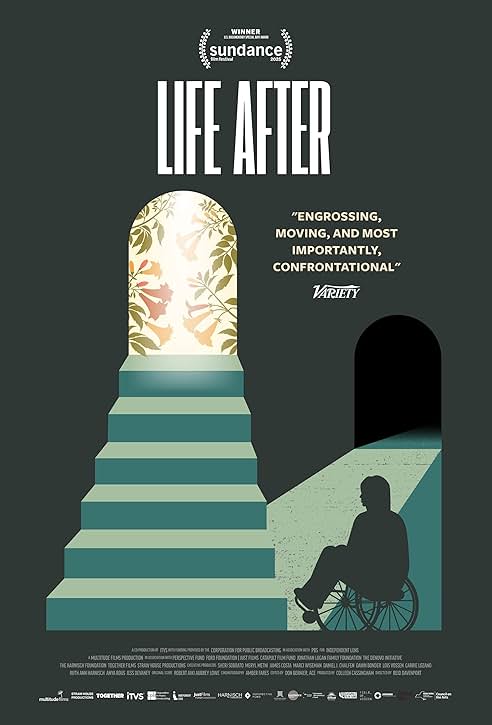

“Life After” (2025) is a documentary that uses California Superior Court’s 1983 decision in Elizabeth Bouvia v. Riverside Hospital case to examine the legal right to euthanasia in Canada and the disabled community’s concern that it will be used to exterminate them even though the Court denied the plaintiff’s assertion of her right to die. Disabled Brooklyn based director Reid Davenport uses the participatory documentary format, which means inserting himself in the narrative thus understandably and overtly putting his thumb on the scale. Davenport condemns the circumstances that lead to disabled people choosing euthanasia instead of directly condemning euthanasia.

In the interest of transparency, after witnessing and attempting to access a panoply of all forms of care ranging from at home care to care in a facility for an ill loved one, I’m coming to this documentary incredibly biased yet not against Davenport’s ultimate thesis just the steps and sweeping conclusions that got him there. The ethics of using Bouvia’s story is something sidestepped, which documentaries like “Seeking Mavis Beacon” (2024) tackled and navigated with grace. To the public, once the case was done, Bouvia stated that she did not want to be contacted or be used as an instrument in this debate. Out of love from her family and rational self-interest from Davenport, Bouvia’s stated wishes are ignored. Instead of the child having autonomy independent from the state and parents, “Life After” and documentaries like “Heightened Scrutiny” (2025) advocate for parents making decisions for the child over the state, which is a tool of the right, i.e. ignoring an individual’s autonomy and choice for benevolent reasons. Davenport is projecting his hopes and fears for his own life on to Bouvia, which he and other disability rights advocates accurately accuse able-bodied proponents of euthanasia of doing with disabled people when passing such laws.

Bouvia is not the only disabled person whose stated desires are dismissed. Davenport takes another case set in 1994 with Jerika Bolen, a fourteen-year-old Black girl who somehow succeeded in getting euthanasia in Wisconsin, as a sign that her community did not support her and cheered her death on more than her life without any proof. He could be right, but it is an extraordinarily callous implication with just using archival radio and television news segments and not revisiting that community to cover the story or stating that he attempted to do so. His basic thesis is that she is too young to make that decision, which is the same argument that the right wing uses about children who belong to the LGBTQ+ community. He deliberately uses dead people who were for euthanasia as his subjects but uses living people who are available to speak out against euthanasia. There does not appear to be an attempt to talk to disabled people in the process of applying for euthanasia. Instead the pain issue, which is a serious and valid concern, gets dismissed. Basically these people get equated with suicidal girls and women who broke up with their romantic partner, which feels misogynistic and infantilizing.

“Life After” also alleges that if able-bodied people cannot get the same treatment, then disabled people should not. So, there was a missed opportunity to tackle that issue and the ethics behind it. Instead of using that argument to expand the right to die, it is used to restrict it. Is psychological pain an insufficient reason to end one’s life? Maybe there is discrimination against able-bodied people with psychological disabilities. Just because an able-bodied person cannot access services does not automatically mean that those services should not be available to disabled people. Davenport conflates suicide with euthanasia and is ultimately squeamish about suicide because he is worried that someone will use it against him. Again, this all or nothing approach feels very conservative. How come these cannot be individual choices? No euthanasia for Davenport, but euthanasia for Bouvia and Bolen.

The conflation of euthanasia with eugenics needed to be teased out more. One speaker suggests, “Most people don’t understand what eugenics is, and if they did, they would find that they agree with much of it.” Davenport never gives this valid statement enough screentime by taking the time to define eugenics and give the historical background before Godwin’s Law could be invoked. After expressing his suspicions of the Hemlock Society, he simplifies its evolution into Compassion & Choices. He does show quotes from Dr. Jack Kevorkian and Peter Singer that are hostile to the existence of disabled people as a drain on society, but their membership with the Hemlock Society is not proven though they are euthanasia proponents. Again, Davenport should show his math because it would make his argument stronger but instead it feels manipulative. In “You Don’t Know Jack” (2010), Dr. Kevorkian is depicted as working with the Hemlock Society, but it is not a fact per se. It is a movie.

Davenport sides with Not Dead Yet, an organization that opposes Compassion & Choices because C&C is not equally working hard to fully fund homecare. To be clear, I’m for fully funded homecare and more options, but you cannot make a group cosign and take on the burden of your issue unless they explicitly oppose it. If Compassion & Choices does oppose it, then they are the enemy, but again, “Life After” does not show the leap in logic. It does show that the Canadian government is overzealous in offering Medical Assistance in Dying to the disabled, but that the administration of government is not the same as someone advocating for the policy of euthanasia. While Davenport may not be deliberately being duplicitous but genuinely feels attacked, it is not the same as showing those feelings are accurate.

“Life After” does feature one fresh argument that deserves its own documentary and would have succeeded where Davenport fell short in bolstering his argument. Sarah Jama, a disability rights advocate at the Disability Justice Network of Ontario, said, “Many people are afraid of disability. They’ve never had to interact with it before. I think its easier for those of us who are born disabled to imagine a future. But when you acquire it when you have an accident or you’re gaining in life, it’s like you’re losing functionality. You’re losing the thing about you that society said made you great and able to be productive. And a lot of the senators and elected officials that I’ve heard from are afraid themselves of aging, and they want autonomy. It’s about a sense of control, and disability really takes that away from you. And I think those of us who are born with it, disabilities, we understand that, but the decisionmakers who are afraid of themselves and what their bodies will look like in the future are really ruining our choices at surviving.” It is likely that not addressing individual members of governments fear of mortality and disability plays a role in the administration. In addition, the justified fear of disability rights advocates also over course corrects by reflexively being against bodily autonomy and the right to die because of their correct fear of what society does to them and ignores the disabled who do want that right.

Importing this Canadian argument in the US is wild even with the deficiencies in this system. If Davenport’s film has a fatal flaw, he should have stayed in the US and explored the euthanasia programs in the states that permitted it. Here is the landscape in the US. You do not have the right to life, which is correctly what disability rights activists want and means the right to be disabled at home, have a life and not be essentially imprisoned in a long-term health care community. You do not have the right to die. “Life After” does reference that Bouvia did get care through government assistance and to receive government assistance, a disabled person must be poor. The story that gets left out: even with government assistance, you will be further disabled regardless of whether you get at home assistance or enter a facility. If you have financial resources, there still may not be any available home assistance, and that assistance will still be inadequate if it can be acquired. In a long-term care facility, whether an assisted living facility or a nursing home, the disability that landed you in that place will not be what kills you. It will be something preventable that will further disable you until you become a victim of negligent homicide. Bouvia died of a lung infection. Davenport leaves out how she got a lung infection as if people should not question why a person with cerebral palsy got a lung infection if medical professionals are actively monitoring them, which Bouvia was. Davenport cares more about death when it is a choice, but not death when it is negligent, which is the more common ground that all people, including disabled ones, face.

Davenport gets really close to this reality when handling examining the case of Michael Hickson, a Black man, which happened in Texas, a state without euthanasia. Instead, Davenport conflates medical racism and refusal to give care like rehabilitation with euthanasia. His medical team wanted to put him into a long-term facility, which led him to getting Covid and dying. This is America-give crap medical care then kill the person through negligence when it gets too expensive, or the money runs out. Hickson’s story deserves its own documentary, but it is deceptive to use this case as an argument against euthanasia. It does support disability rights. Davenport could have used Jani McMath’s case, which involves race, gender, disability and euthanasia since it started in California, and the child and family did not consent to the hospital’s declaration of her brain death.

“Life After” is not a cynical documentary. It is a manipulative one paved with good intentions and armed with historical knowledge that we are in the worst timeline. It is totally valid for anyone in this film to be apprehensive and suspect motives, but not at the price of others’ autonomy and rights.