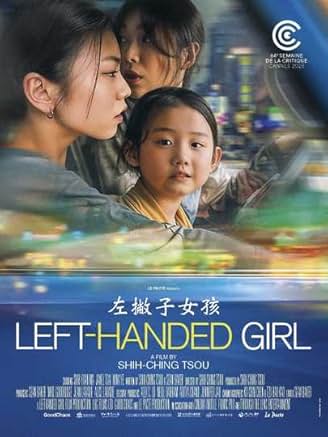

“Left-Handed Girl” (2025) is Taiwan’s submission to the 2026 Oscars’ “Best International Feature” category. Director and cowriter Shih-Ching Tsou teams up again with her frequent collaborator cowriter Sean Baker, but this time, instead of producing or sharing the director credit, she is the only one in the director’s seat. Set in her hometown, Taipei, the film follows Shu-Fen (Janet Tsai), her older daughter, I-Ann (Shih-Yuan Ma), and youngest I-Jing (Nina Ye) as they adjust to life in a big city. It seems as if the troubles pile up and ruin their fresh start. Will they fall apart or come together? This unpredictable film shows how rough the world can be, but Tsou’s first feature pulls back from the edge of the abyss without pulling too many punches.

“Left-Handed Girl” lives on the natural chemistry of this ensemble cast, but I-Ann and I-Jing take turns at being the protagonist. Even though she lives in big city, it is a safe place for a kid to navigate with everyone keeping an eye out for her as she becomes a well-known fixture at the night market, but if everyone is looking out for her, no one is. I-Ann is perfunctory in performing her big sister duties. Shu-Fen is preoccupied with money falling short, and the bills piling up. When the maternal grandfather (Akio Chen), who is at times her primary caretaker, notices that I-Jing only uses her left hand, he introduces I-Jing to the concept of evil, and she begins to wonder if there is something innately wrong with her. This concern sucks the joy out of daily life, and it is a genuinely distressing story line that gets very close to becoming harrowingly disastrous.

A major theme in “Left-Handed Girl” is which characters’ deficiencies are excused or forgiven, and which ones get paraded for shame and ridicule. Gender, age and class are unsurprisingly determining factors that tip the scale one way or the other. The maternal grandmother (Xin-Yan Chao) is involved in something that seems relatively harmless, but illegal; however, it is tacitly approved because everyone financially benefits, and it provides her with a social outlet.

With her sixtieth birthday coming up, even though Shu-Fen’s sisters, Xiao-hong (Blaire Chan) and Xiao-Ang (Zhang Yunxi), are planning it, Shu-Fen is stigmatized for not being able to contribute, but their brother will get all the credit for only existing. Shu-Fen is the black sheep in her family because she is always borrowing money from her mother. The full story of how she became a single mother is never fully revealed, but hints are dropped here and there. Her inclination to forgive lands her and her immediate family in deeper trouble.

In contrast, children do not respect their fathers in action or deed, but wives excuse their husbands. When Shu-fen’s brother arrives, he holds out a chair for his mom but basically ignores his father. I-Ann is furious at her father when he resurfaces to make life more difficult, but Shu-Fen devotes more time to him than the younger members of the family, which puts everyone in more danger. A wife defends her cheating, deceptive husband even though she knows that he lied to the other woman about their marital status.

In contrast, I-Ann cannot catch a break in any demographic, which partially explains her anger when she sees men skirting consequences. I-Ann’s fashion choices reveal a lot of skin. Ma has an Anja Taylor-Joy quality to her organic, soulful performance. Her character works as a betel nut beauty at a brightly lit shop, which is associated with sex work because the stimulant is sold to working class men who need to stay awake. “2 for 1” implies that they exchange more than just the advertised product, and a hint is offered considering how I-Ann interacts with her boss in one scene with audible slurping sounds. I-Ann is brusque and rough with the world, but her attitude changes at times when she has patience to deal I-Jing or she reacquaints herself with people that she knew before they left Taipei.

Like any Baker film, there will be sex work; however, Tsou makes this world a relatively kinder place. She starts at the bottom, then goes lower before alleviating the pressure. Johnny (Teng-Hui Huang), who owns a neighboring market stall, seems to have a soft spot for Shu-Fen and looks out for the entire family. While there are no literal supernatural forces at play, there is “A Prayer for Owen Meany” quality to I-Jing’s wandering and sudden fear of her hand. It may remind horror fans of movies where there is a hand transplant, and the former owner was a criminal, so the hand retains its original owner’s deficiencies except it winds up being called “God’s hand” due to a set of fortuitous events. The most stigmatized part of a person serves a redemptive quality that saves everyone because of the ripple effect that would have come from a member of the family’s downfall.

Like “Tangerine” (2015), Tsou shot this film using an iPhone. The handheld approach makes moviegoers experience the city like the characters. Tsou often shows the world through I-Jing’s eyes such as the kaleidoscope filtered opening credits. I-Jing sees everything as magical and adjusts to city life immediately. That magic works both ways as the news amplifies the family’s actions without naming and scandalizing them. It is an absurdist surreal touch. They experience city life like a movie where they are the central attraction without being given the star, luxurious treatment. The spotlight of notoriety just misses them as if they are being protected with the veil lifted just enough to erase posturing or playing a role in their family life instead of being authentic.

“Left-Handed Girl” creates a world where the goal is to erase shame for everyone with mixed results. There is an idea that if everyone owns their mistakes, it is possible to still be a part of community instead of hiding it. It is a fallen world that holds constant peril and is not suited for life while also being a magical place where an almost naked and unashamed woman could move with the speed of Hermes thanks to their motorbikes. It is a sweet notion of small-town life in a big, bustling city and being satisfied with where one is or making everything romantic. Tsou and Baker’s films always feel real. Apartments in their movies look like apartments in real life and feel lived in, not a catalogue or preserved like a museum. By staying grounded in the minutiae of the story, the fantastical possibility of supernatural forces protecting this family from further harm thanks to a special little girl seems feasible.

“Left-Handed Girl” is a beautiful love letter to a flawed multigenerational family trapped in the condemnation of societal roles that do not serve them. Once they accept that life just is, mistakes happen and errors are not meant to be punished forever, it gives them a freedom to enjoy the simple pleasures of life together instead of being trapped in their heads and bruised in their every waking moment.