Pedro Almodovar is one of the greatest living film directors, the rightful heir to Hitchcock’s throne with his mix of psychosexual driven dramas and an innovative storyteller who delivers uniquely crafted narratives. When Hulu notified me that his films were going to expire and be removed on June 20, 2017, I decided to watch all his films, including the ones that I already saw. This review is the first in a summer series that reflect on his films and contains spoilers.

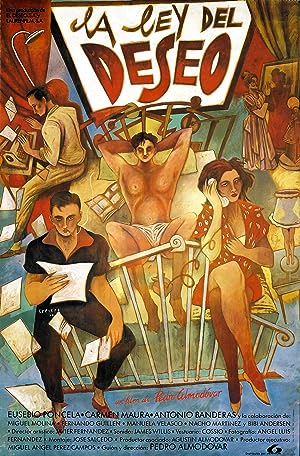

I started with Law of Desire, which I have never seen before. Law of Desire is about a gay filmmaker and his transsexual sister as their careers, stories and love lives are inextricably, lovingly and destructively combined. Almodovar’s movies usually commence with a moment of confusion for the audience: are we watching fact or fiction? As an audience, we know that we are actually watching fiction, but in the context of the depiction on screen, we have to ask ourselves what is real and what is Memorex. This disorientation further deepens as the film progresses when we are finally introduced to the main characters. It is not until later in the film that I fully realized what was going on. This confusion helps us empathize and not judge the characters on screen.

The siblings self medicate with illegal drugs throughout Law of Desire. While their use seems celebratory, it is constant and suggests that their bon vivant attitude is a hard won battle against pain. Others’ identities are less solid and stable. Law of Desire is emblematic of Almodovar’s talent of simultaneously making us sympathize with severely flawed characters that act in objectively awful ways while not diminishing the heinousness of the act, the victim’s injury or the madness of the individual. He takes their emotions, usually love and obsession, seriously. If you see Antonio Banderas in an Almodovar film, assume that his character is probably batshit crazy or suspect in some way, but Almodovar still gives his mad characters credibility. A madman can love or love can drive someone mad. The madman in an Almodovar film acts as a cautionary tale for the main character about how far he or she should be willing to go for love. Go too far, and you risk losing yourself.

Law of Desire is set in the 80s, which makes it a bit dated. There is a sexual fluidity and permissiveness in this film, which is usually implied, not depicted, in his later films. Even though the filmmaker is clearly gay, his lovers appear to be bisexual or initially heterosexual. While these lovers notice him because of his fame, he is not being exploited for a role or money. Almodovar sees filmmakers as cursed priests that people feel compelled to go to, but then these filmmakers are gutted by their stories and need. Art as explosive and destructive explains the magical realism elements in the final act of the film.

Before the world knew that transsexuals existed, Almodovar had transsexuals as major three-dimensional characters in his films. In Law of Desire, the transsexual character is a transwoman played by a cis woman so it took me awhile to realize that she was supposed to be a transwoman, not a cis woman. She has trouble finding work that is not in some way related to curiosity about her body or sex. Her take on her life is optimistic, but it is marked by sexual abuse or exploitation mistaken for love by a priest, her father and her second attempt at love. Even her beloved brother, who loves her for who she is and not for what he can get from her, is guilty to some degree of appropriating her pain and past for art. The church that abused her rejects her. She is trying to be a good parent and is the best available parent, but has no frame of reference on what is and is not appropriate for a child because of her own experiences or maybe it is entirely appropriate to expose her child to the world so she can wisely navigate it and know what to reject.

Law of Desire initially seems like a story about two siblings, but it suddenly becomes evident that it was always a murder mystery. I didn’t realize that seemingly insignificant moments early in the film (getting an expensive shirt, letters about wanting to forget a lover, use of alias between lovers, writing a letter for someone else) were actually pivotal clues to what happens in the second half of the film. The crime being investigated is their lives. They are guilty for existing, being gay and transsexual. Almodovar gives us a world where they are respected and can live then pulls back to show how fragile and tiny that world actually is. Even in a largely hostile world, there are secret allies who try to help them: the medical community (plastic surgery is not a negative in an Almodovar film) and one uniformed police officer.

The Hitchcock film style becomes more evident in the second half of the film. When the filmmaker is driving, there is a shot of the wheels dissolving into his eyes, and we see the filmmakers’ point of view. The sister rushes forward through a hospital corridor and is matched by the camera pulling back at the same rate. Almodovar’s camera work emotionally communicates information to the viewer that no dialogue can do. He understands that films are primarily visual, and multitasking is impossible when watching one of his films. An Almodovar film demands your complete attention.

Law of Desire is a must see film for Almodovar fans, but probably should be avoided by newcomers who could be sensitive to its provocative nature and frank sexual depictions.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.